Eighth Grade

By Brian Eggert |

A recent surge of coming-of-age indie films has shifted the focus away from teenage boys and considered, for a change, the emotional confusion experienced by teenage girls with increasing resonance. Most recently in 2016, Kelly Fremon Craig adopted a John Hughes tone for her often hilarious, sometimes aching The Edge of Seventeen, featuring actress-turned-pop-star Hailee Steinfeld as a jumbled high-schooler. Last year’s Lady Bird found Saoirse Ronan performing in a confused, semi-autobiographical role for first-time helmer Greta Gerwig, capturing, in an idiosyncratic yet truthful style, that brief and puzzling transition from adolescence to adulthood. The honesty of both titles makes Juno, released in 2007 to wild approvals, look kitschy, absurd, and guarded by comparison. Those later films marked outstanding debuts for their female writer-directors, both brimming talents, and weighed the later years of teendom with emotional perspective and insight. Eighth Grade marks another sort of debut, diverting from these other teen stories not only in terms of its voice, but also its subject matter.

After all, high school is much more palatable than middle school (or, depending on your experience, junior high). Most high school teens, while hardly close to having their lives figured out, have moved beyond the growing pains of middle school—a period where the raging hormones and insecurity of later teen years is amplified to delirious extremes. An unforgiving social gauntlet in which every weakness is exploited and mocked, lack of confidence dominates everyday existence, and the human body makes a series of hairy and greasy maneuvers no living being—not even the most popular—could properly adjust to, middle school is a nightmare. Somehow, freshman writer-director Bo Burnham tackles this period of adolescence with the sensitivity and insight of someone sympathetic and acutely aware of their experiences from those years. And while accurately representing the vulnerability that everyone feels during that period of our lives, he engages the material with humor to acknowledge the absurdity of this age, but his empathy never subsides.

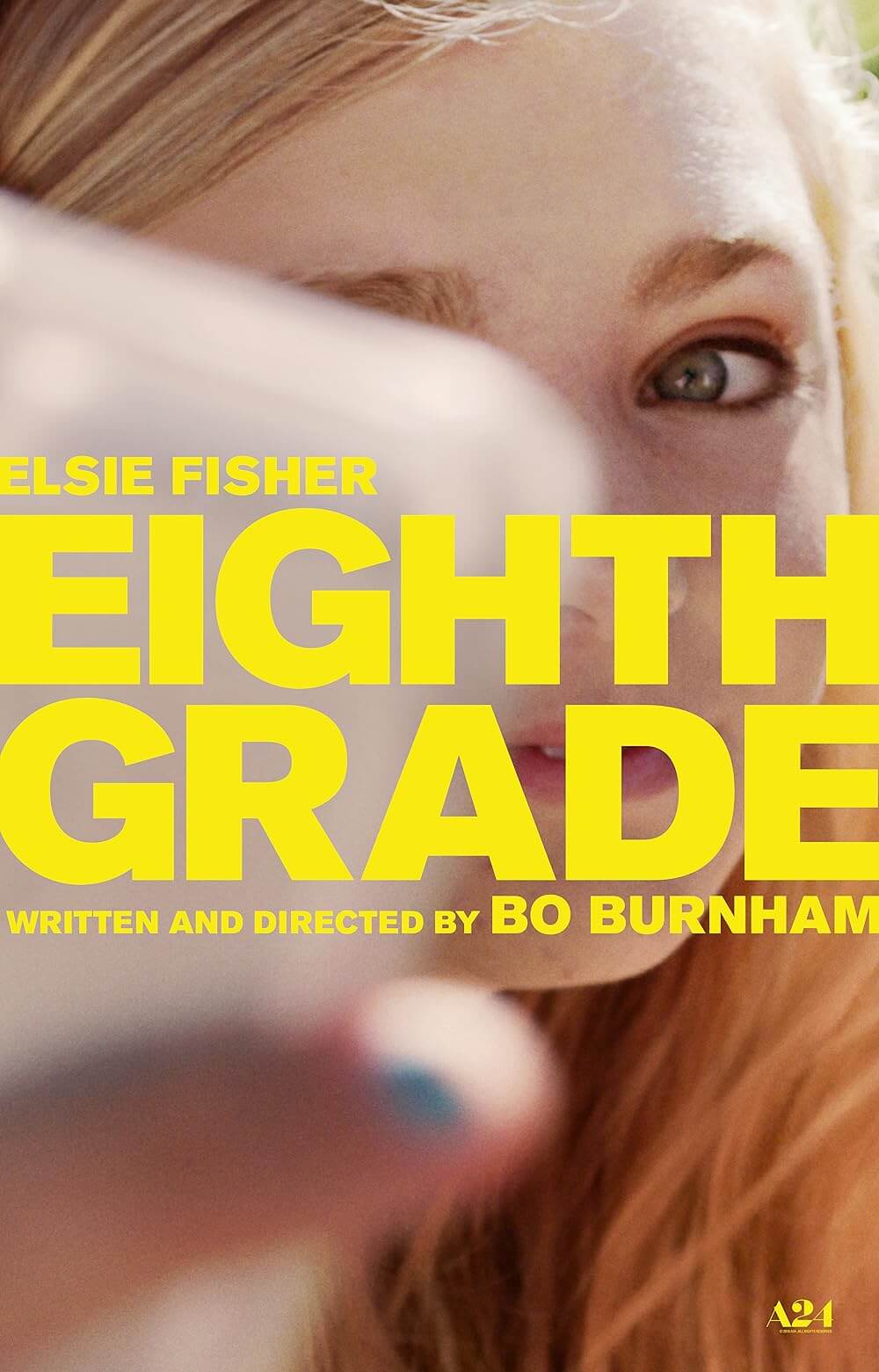

Though Eighth Grade is about today’s teenaged Generation Z, Burnham remains a prototypical Millennial voice, having earned his fame in his early twenties through comical music videos on YouTube. He’s since toured as a stand-up comedian whose stage routines involve elaborate, almost artistic performances, blending absurdist humor with music and a surprising rawness. His latest special on Netflix from 2016, titled Make Happy, features more than one reference to his disapproving father, as well as his conflicted relationship with his audience—his own disgust over his need for validation through his audience’s approval. Perhaps because of his origins on and relationship with social media and its inherent self-absorption, Burnham understands better than most how important acquiring likes and follows remain for the teenagers of today. That’s an essential component of life for Kayla (Elsie Fisher), the shy 13-year-old at the center of Burnham’s debut.

Kayla has bad posture and complexion, has no friends in school, and recently won her class award for “Most Shy”—but she’s trying. Every day, she sits before a webcam and makes videos for her underwhelming number of subscribers, talking about subjects such as “Putting Yourself Out There” with an authority she has not yet mastered. She desperately wants to feel socially accepted, although her awkwardness and inhibition seem to outweigh her longing to make friends or, further, obtain a boyfriend. Loud, intense electronic music cuts into the film’s score when she spies her crush (Luke Prael), a dreamy douche bag only interested in blowjobs and making squeaky fart sounds with his mouth. Kayla tries to engage, but she’s barely noticed by the elitist cool crowd she so admires. Still, she refuses to retreat into self-imposed isolation as a response to cold shoulders or her social anxiety. When Kayla is begrudgingly invited to the pool party of the middle school’s resident social butterfly and mean girl, she attends, even though she fumbles through almost every encounter.

A character like Kayla could have been a punching bag for another filmmaker, like Todd Solondz’s Dawn Weiner in the merciless Welcome to the Dollhouse (1996). Instead, Burnham ultimately delivers a sweet, understanding portrait of a particularly brutal and rejection-inflected period. He resists making his character too self-aware, so she never feels like a character written by an adult looking back on their own experiences. He directs naturalistic performances, especially from Fisher, whose primary experience has been voicing the fluffy-exclaiming Agnes from Despicable Me and its sequels. Fisher, behind her character’s crutch of vocalized pauses and resistance to eye contact, captures what it feels like to exist in an unwelcoming world and feel alone, and her tenderness, marked with bouts of rattled interactions and humiliation, occasionally brings the viewer to tears. Meanwhile, her single father, played with pitch-perfect confusion and blind supportiveness by Josh Hamilton, tries his best to lighten the evident burden on his daughter. However, Kayla seems determined to go it alone, assuring her father, “You don’t need to worry about me anymore.”

Burnham’s style of humor in Eighth Grade often relies on cringe-comedy, although never cruelly so, and not exclusively targeted against Kayla. Her father bears the brunt, such as a scene where Kayla asks him to help her burn something in the backyard. Cautious, he agrees, which is already an exceptionally supportive choice. When he finds out what they’re burning, contained within a shoebox, the moment becomes tragically funny. Although the humor sometimes places Kayla or her father at the center of a joke, they’re never the butt of the joke or mocked. That distinction is significant to maintain the film’s astounding balancing act between a coming-of-age comedy and a heartrendingly precise depiction of teenage insecurity. It allows Kayla’s inner life, however transitory and small in the grand scheme, to carry gravity. Still, Burnham’s observations of teenage behavior remain riotous and touching, such as Kayla’s first friend date with a boy, who serves her a classy dinner of chicken nuggets and fries with an (un)healthy variety of dipping sauces.

A streak of social and generational observation also comes through in Eighth Grade, as evidenced in a scene where Kayla shadows a high-school mentor, who later invites her to the mall. There, an older teen boy remarks that Kayla’s generation, though only four years apart, is “wired differently” because they were introduced to Snapchat in the fifth grade. Older viewers of Eighth Grade may have trouble relating to younger generations because their lives are seemingly defined by their smartphones and social media profiles. Such differences remain superficial, Burnham seems to argue. No matter your generation or gender, Kayla’s experiences throughout the film prove relatable. With perspective, the things that seem monumental in her life may be inconsequential later, but Burnham superbly puts the viewer in her world and reminds us that we, too, once writhed in our skin over the trivialities that overran our everyday existence. Another generational difference is presented with sobering matter-of-factness when Kayla’s class undergoes training on how to respond in the event of a school shooting, and the students treat their instruction with a saddening degree of normality.

Ridiculously, Eighth Grade has been rated R by the MPAA (for language and a sexual reference), meaning the audience on which it’s based cannot see the film without a parent. While parents may find watching the film with their teen child a tad uncomfortable, many children of this age will undoubtedly find much to identify with, and in a way, its catharsis may prove therapeutic. If you’re a parent, consider buying your teen a ticket and picking them up afterward; they’ll thank you for it. Whether you’re experiencing the woes of middle school now, or looking back from years later, incredulous and maybe still a little angry about the narrowly survived social hell and uncertainty during that stage of your life, Burnham offers a warm, emotionally vital snapshot of adolescence. Eighth Grade is one of those rare films that speaks to everyone, regardless of its subjective specificity, through universal life lessons that every person must learn and overcome before becoming an adult. It allows us to look at that age with humor and compassion, while putting equal weight on the absurdities and heartbreaking truths of eighth grade.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review