Reader's Choice

Eastern Promises

By Brian Eggert |

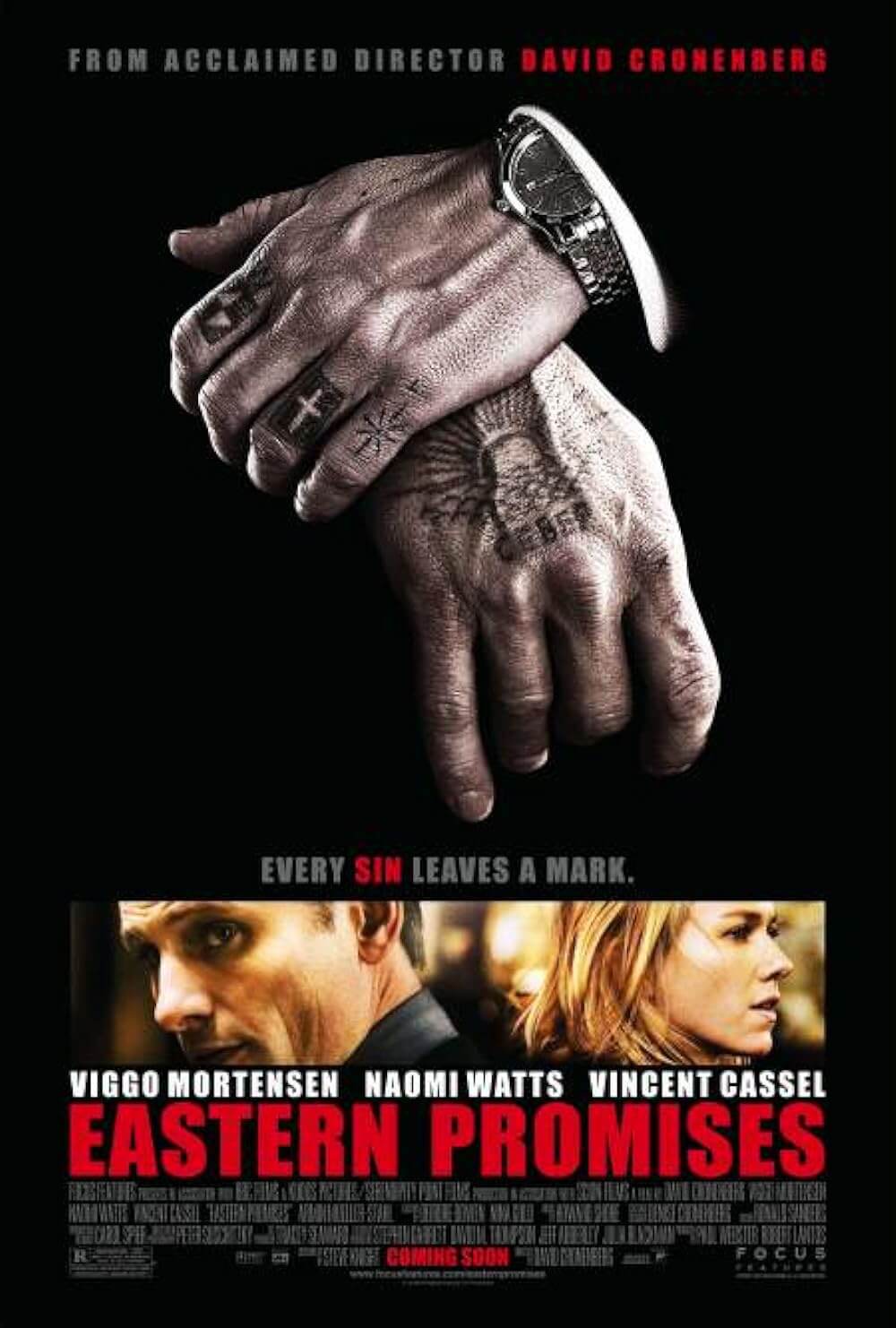

Our bodies tell stories. Every bruise alludes to an action. Each scar describes a trauma. Inside, blood and DNA chart family history and imply a heritage, the knowledge of which may draw us closer to our past. David Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises explores how the body preserves identity. But in the 2007 film written by Steven Knight, physical signifiers also deceive and keep secrets. Following Cronenberg’s A History of Violence (2005), Viggo Mortensen plays another enigmatic character with a violent past. Mortensen is Nikolai, a functionary in the Russian mob in London—the vory v zákone (meaning “thieves-in-law”)—whose elaborate tattoos, acquired in a Siberian prison, read like a résumé of his past crimes inscribed on skin paper. More than body art, his tattoos convey both the misdeeds that earned them and the guile of their creation. Yet, along with Nikolai’s corporeal vita, little is what it appears to be in the film—especially the outward promise of freedom in the West. Beyond the film’s eroticized violence and secretive world among the brutal Russian gangsters, Cronenberg also tells an immigrant story about people who want a better life only to find their yearning exploited. They have arrived in contemporary London only to face a Dickensian, unforgiving, and violent underworld.

Eastern Promises opens with two traumatic scenes, and Knight, no stranger to literary symbolism, sets them on December 20, the eve of the darkest day of the year. The first scene in a London barbershop involves the gruesome throat-slicing hit of a soldier in the Chechen mob. The next scene finds Tatiana (Sarah Jeanne Labrosse), a 14-year-old addict, barefoot, bleeding, and going into labor. Tragically, Tatiana dies, leaving Anna (Naomi Watts), the midwife who delivered the baby, to search for a relative to keep the baby out of the foster system. She finds Tatiana’s diary in the maternity ward and inside discovers a card for the Trans-Siberian Restaurant, then visits the owner, Semyon (Armin Mueller-Stahl), to ask for help. Although he appears gentle and soft-spoken with kind eyes, Semyon is a godfather-like patriarch of the vory v zákone, unbeknownst to Anna. His organization thrives on human trafficking, drugs, and prostitution, among other vices. Not only is he responsible for Tatiana’s exploitation, but he trafficked her from Russia, then raped and impregnated her before installing her in his sex trade. Hiding this fact, Semyon presents himself as a kindly figure, offering to teach Anna about her Russian roots while agreeing to translate Tatiana’s diary. However, when Anna brings Semyon photocopies of the diary’s pages, he asks where she lives and insists on getting the original so that he can destroy the evidence of his criminality.

Eastern Promises frames Anna’s search for Tatiana’s family as an act of personal healing after her own trauma. Part Russian on her father’s side, Anna lives with her mother (Sinéad Cusack) while recovering from a recent breakup and miscarriage. Her irascible uncle Stepan (Polish director Jerzy Skolimowski), an ex-KGB operative, escaped his former life for the promises of the so-called Free West. He believes Anna should take Tatiana’s diary and “bury her secrets with her bodies”—a loaded mispronunciation, to be sure. A racist and traditionalist, Stepan remains disillusioned by London’s corruption—portrayed by Cronenberg and cinematographer Peter Suschitzky in gray, empty urban spaces across a damp, indifferent metropolis. The setting of immigrant communities struggling in an exploitative abyss cannot help but recall another Knight-penned story, 2002’s Dirty Pretty Things, directed by Stephen Frears, wherein immigrants find themselves preyed upon by black-market organ traffickers. When Stepan translates the diary and confirms the worst about Semyon, Anna recognizes the everyday cruelty that inhabits London, Tatiana’s would-be promised land. This glimpse at Anna’s home life, along with Tatiana’s fate, underscores the title’s reference to the false promises made in the East about the opportunities in the West.

Eastern Promises frames Anna’s search for Tatiana’s family as an act of personal healing after her own trauma. Part Russian on her father’s side, Anna lives with her mother (Sinéad Cusack) while recovering from a recent breakup and miscarriage. Her irascible uncle Stepan (Polish director Jerzy Skolimowski), an ex-KGB operative, escaped his former life for the promises of the so-called Free West. He believes Anna should take Tatiana’s diary and “bury her secrets with her bodies”—a loaded mispronunciation, to be sure. A racist and traditionalist, Stepan remains disillusioned by London’s corruption—portrayed by Cronenberg and cinematographer Peter Suschitzky in gray, empty urban spaces across a damp, indifferent metropolis. The setting of immigrant communities struggling in an exploitative abyss cannot help but recall another Knight-penned story, 2002’s Dirty Pretty Things, directed by Stephen Frears, wherein immigrants find themselves preyed upon by black-market organ traffickers. When Stepan translates the diary and confirms the worst about Semyon, Anna recognizes the everyday cruelty that inhabits London, Tatiana’s would-be promised land. This glimpse at Anna’s home life, along with Tatiana’s fate, underscores the title’s reference to the false promises made in the East about the opportunities in the West.

Knight weaves together efficient plotting and complex characters in just 100 minutes, balancing Anna’s search for answers with two intensifying conflicts: the war between Russian and Chechen mobs, and questions about Semyon’s successor. His unpredictable son, Kirill (Vincent Cassel), has ignited the mafia conflict with an unauthorized hit of a man who spread rumors about Kirill’s drinking and sexuality. In Cronenberg’s portrait of this all-male subculture, accented by homoeroticism, everyone appears to be family yet viciously competing and controlling one another. Semyon comes to rely on Nikolai, Kirill’s driver and bodyguard, to keep his son out of trouble. However, the relationship between Kirill and Nikolai is more complex than employer-employee. Kirill calls Nikolai a “brother” and “partner,” yet he also orders Nikolai around like a servant. Note the scene where Kirill’s twisted sense of camaraderie demands that Nikolai have sex with a prostitute while he watches, seemingly to prove that Nikolai isn’t gay and thus good enough for his father’s syndicate. Throughout the film, the touching between Kirill and Nikolai walks the line between brotherly and flirtatious—with arms around the shoulders and slaps on the butt—though Cronenberg doesn’t shed light on whether Nikolai is manipulating Kirill in these terms or feels genuine empathy or both. Kirill’s repressed sexual curiosity about Nikolai stems from his father’s vocal homophobia, resulting in a disturbed character whose identity is criminal but tragic.

Although Eastern Promises eschews Cronenberg’s usual science-fiction and horror narrative elements, Cronenberg doesn’t forego bodily themes. Here, Nikolai’s tattoos are symbols, raw and visible. Russian prisoners tattoo their life stories onto their bodies; the tattoos signify their crimes, where they served, and what qualifies them for their membership in the vory v zákone. Whatever the tattoo shows must be true. As Nikolai earns Semyon’s trust, he goes through a ritualized screening process, standing in front of several mob figures, baring his tattoos, thus himself. Curiously, the tattoo theme wasn’t in Knight’s original script. During his research for the role, Mortensen discovered the relationship between Russian gangsters and tattooing from the 2003 book Russian Criminal Tattoo and the documentary The Mark of Cain (2001). When Mortensen brought the concept to Cronenberg, the director found the practice a generous symbolic theme and worked with Knight to rewrite the script with Mortensen’s research. But Nikolai’s body lies; his tattooing is part of an elaborate undercover case for the Russian FSB (formerly KGB) to destabilize the vory v zákone in London. Although Nikolai’s body suggests tangible proof of his criminal worth, both in terms of the tattoos it bears and as a singular physical specimen, Cronenberg scholar Ernest Mathijs notes that his fraud “undermines the stereotypically masculine sense of authenticity and heroism associated with the survival of painful ordeals and danger.” Sure enough, when Nikolai is awarded the tattooed stars of a vor on his chest, it’s so Semyon can redirect Kirill’s Chechen enemies to kill Nikolai instead of his son.

Whatever deception Nikolai’s tattoos contain, he demonstrates his skills in the unforgettable, gasp-inducing fight in a Turkish bathhouse. Kirill’s hasty assassination of his slanderer causes a series of reprisals, one of which finds Nikolai attacked. Mortensen insisted that he perform the sequence naked and vulnerable, almost like a Greek athlete performing in the earliest Olympic games. Baring all, Mortensen’s naked character savagely fights off two thugs in the bathhouse. Everything suggested by Nikolai’s tattoos is confirmed here—making the subsequent reveal of his deception all the more shocking—since his raw, masculine violence is unleashed with unrelenting savagery. Cronenberg admitted the script described the scene as “Two men come in with knives and there’s a fight.” The details—the nakedness, steam, fight choreography, and curved linoleum knives—came from the director working out the details with Mortensen, Suschitzky, stunt coordinators, and production designer Carol Spier. Some critics claimed the scene marked Cronenberg’s comic indulgence in borderline horror-genre violence; some claimed the scene emphasized the film’s homoeroticism; and some argued that the scene’s convincing physicality, along with other moments of violence in the film, suggested the story’s place in the real world. Anthony Lane asked in The New Yorker, “Why go that far? Must he cling to his schlocky reputation at all costs?” Doubtless, the reality of actual gang violence looks much worse than Cronenberg portrays.

Whatever deception Nikolai’s tattoos contain, he demonstrates his skills in the unforgettable, gasp-inducing fight in a Turkish bathhouse. Kirill’s hasty assassination of his slanderer causes a series of reprisals, one of which finds Nikolai attacked. Mortensen insisted that he perform the sequence naked and vulnerable, almost like a Greek athlete performing in the earliest Olympic games. Baring all, Mortensen’s naked character savagely fights off two thugs in the bathhouse. Everything suggested by Nikolai’s tattoos is confirmed here—making the subsequent reveal of his deception all the more shocking—since his raw, masculine violence is unleashed with unrelenting savagery. Cronenberg admitted the script described the scene as “Two men come in with knives and there’s a fight.” The details—the nakedness, steam, fight choreography, and curved linoleum knives—came from the director working out the details with Mortensen, Suschitzky, stunt coordinators, and production designer Carol Spier. Some critics claimed the scene marked Cronenberg’s comic indulgence in borderline horror-genre violence; some claimed the scene emphasized the film’s homoeroticism; and some argued that the scene’s convincing physicality, along with other moments of violence in the film, suggested the story’s place in the real world. Anthony Lane asked in The New Yorker, “Why go that far? Must he cling to his schlocky reputation at all costs?” Doubtless, the reality of actual gang violence looks much worse than Cronenberg portrays.

Still, the Canadian auteur has never been one to shy away from the physical reality of his subjects, especially where violence and sex are concerned. Moreover, the violence is not without purpose; it reveals the unrelenting physical punishment Nikolai must endure for his undercover mission. Mortensen even manages a darkly comic tone to Nikolai throughout the fight scene, captured in his almost disgruntled expressions—as though he understands what has happened and why, and furthermore, knows what’s in store. After surviving the ordeal, he orders Semyon to be arrested for statutory rape, using the baby’s DNA as evidence. But Semyon has already ordered Kirill to dispose of the child. Nikolai and Anna rush to the scene to stop him, and they find Kirill breaking down over nearly losing his friend and being ordered to kill a child. “You’re either with him or with me,” Nikolai tells him. The two embrace like old friends and, perhaps, imminent lovers. But the connections between Nikolai and Anna remain more substantive. Eastern Promises draws a parallel between Anna and Nikolai as outsiders and survivors. Neither character belongs to the ritualized Russian culture on display in the film. Anna feels some faint connection to her heritage through her father and uncle, but her experience with Semyon dissuades her. Nikolai pretends to belong, wearing a figurative mask to infiltrate the inner circle. So naturally, Knight arranges for a romantic flourish at the end, hinting at what might have been in a makeshift family between Nikolai, Anna, and Tatiana’s baby.

In their discussion of A History of Violence and Eastern Promises, scholars Aron Dunlap and Joshua Delpech-Ramey note the place of women in Cronenberg’s earlier films as “passive victims of either experiment or psychosis. They are either spectators to or accomplices with the inchoate, irrational, and alien materialities that men attempt to control.” However, they acknowledge that women have more agency in these films as male characters “move from horror to fascination to acceptance of the grotesque.” In Eastern Promises, Anna works in union with Nikolai, even though his true identity remains elusive, almost nonexistent to the viewer. Neither Anna nor the viewer learns Nikolai’s real name. His past, evidenced by his tattoos, is a complete fabrication. His future, promised by the stars tattooed on his chest, is false since Nikolai hopes to achieve the rank to uninstall it (“How can I become king, if the king is still in place?” he asks). Nikolai is not a hero who ascends to the role of a mob boss but a figure of deception. We see no true Nikolai, not even when he is stripped bare; there is only a series of false truths and yet-unrealized objectives.

Whereas Nikolai remains trapped and his body, which is reshaped to propel a deception, thus never his true self, Anna presents a bold alternative. Dunlap and Delpech-Ramey describe Anna as “a gorgeous study in the enigmatic nature of subtle heroism.” Riding around London in high leather boots on a motorbike, Anna takes direct and unwavering action. In Lacanian psychoanalytic terms, Nikolai has emasculated himself by performing in a symbolic, indirect way through his undercover ruse and false history inscribed by his tattoos. By contrast, Anna adopts the traditionally more masculine role through her willingness to face a conflict head-on, not in symbolic terms. Her initial intention of rescuing Tatiana’s baby, regardless of stemming from her stereotypically feminine role as a midwife, situates her in the traditional masculine hero role. Anna is wholly unique in Cronenberg’s cinema, which tends to focus on men and women in relation to men. Moreover, she remains one of the film’s only characters who is what she appears to be: Semyon presents himself as a restauranteur to hide his criminal enterprise; Kirill pretends to be heterosexual to disguise his likely queerness; Nikolai adopts a false front to convince everyone he’s a career criminal. The film’s world of men is deceptive, making Eastern Promises an uncharacteristically feminist world in a Cronenberg film. Even Tatiana’s phantom voiceover from her diary situates the narrative as looking onto a male-dominated world from a feminine perspective.

Whereas Nikolai remains trapped and his body, which is reshaped to propel a deception, thus never his true self, Anna presents a bold alternative. Dunlap and Delpech-Ramey describe Anna as “a gorgeous study in the enigmatic nature of subtle heroism.” Riding around London in high leather boots on a motorbike, Anna takes direct and unwavering action. In Lacanian psychoanalytic terms, Nikolai has emasculated himself by performing in a symbolic, indirect way through his undercover ruse and false history inscribed by his tattoos. By contrast, Anna adopts the traditionally more masculine role through her willingness to face a conflict head-on, not in symbolic terms. Her initial intention of rescuing Tatiana’s baby, regardless of stemming from her stereotypically feminine role as a midwife, situates her in the traditional masculine hero role. Anna is wholly unique in Cronenberg’s cinema, which tends to focus on men and women in relation to men. Moreover, she remains one of the film’s only characters who is what she appears to be: Semyon presents himself as a restauranteur to hide his criminal enterprise; Kirill pretends to be heterosexual to disguise his likely queerness; Nikolai adopts a false front to convince everyone he’s a career criminal. The film’s world of men is deceptive, making Eastern Promises an uncharacteristically feminist world in a Cronenberg film. Even Tatiana’s phantom voiceover from her diary situates the narrative as looking onto a male-dominated world from a feminine perspective.

If Eastern Promises begins as a film about the Russian mafia, it ends as a complex character study less interested in the machinations of criminal organizations. Cronenberg centers his interest on people who disguise themselves in various ways or exist as outsiders. As ever, the director remains fascinated by deviations of the body, institutions, and social norms. And anchored by one of Knight’s best scripts—he would go on to write Spencer (2021), Allied (2016), and create TV’s Peaky Blinders (2013-2022)—Eastern Promises shows Cronenberg’s ability to develop material to suit his preoccupations. The film also presents a stunning inclusion in his filmography as his second collaboration with Mortensen, who disappears into his role and brings an unsettling authenticity to every deliberate gesture. After viewing Eastern Promises once and learning its secrets, Mortensen’s performance rewards additional screenings with his outward control that nonetheless bears faint micro-gestured hints at his identity. Indeed, similar to A History of Violence, Cronenberg imbues a seemingly straightforward and commercial crime story with substance and layers as only a master filmmaker could.

(Note: This review was originally suggested on and posted to Patreon on April 4, 2022.)

Bibliography:

Beard, William. The Artist as Monster: The Cinema of David Cronenberg. University of Toronto Press, 2006.

Browning, Mark. David Cronenberg: Author or Filmmaker? Intellect, Ltd., 2007.

Dunlap, Aron, and Joshua Delpech-Ramey. “Grotesque Normals: Cronenberg’s Recent Men and Women.” Discourse, vol. 32, no. 3, Wayne State University Press, 2010, pp. 321–37, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389855.

Lane, Anthony. “Space Cases.” The New Yorker, 10 September 2007. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/09/17/space-cases. Accessed 18 March 2022.

Mathijs, Ernest. The Cinema of David Cronenberg: From Baron of Blood to Cultural Hero. Wallflower Press, 2008.

Taubin, Amy. “Foreign Affairs.” Film Comment, Sept-Oct 2007.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review