Earth Mama

By Brian Eggert |

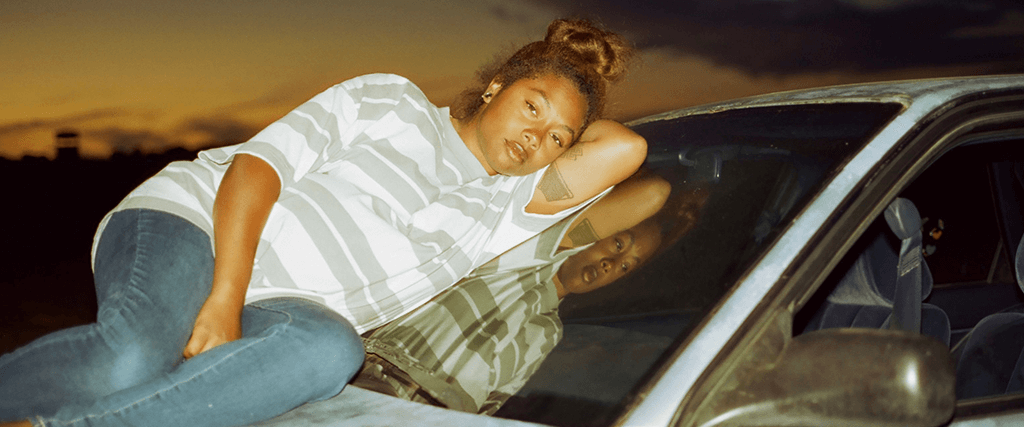

Savanah Leaf’s boldly confident debut feature Earth Mama is a film that, at first blush, looks like a docudrama about the foster care system. While it does tell the story of a Black mother with two children as wards of the state and another one on the way, facing a bureaucratic no-win situation, Leaf’s pensive and heartening tale immerses us in its protagonist’s dreamy perspective at times. The film breaks from a style that might be called purely authentic, exploring an occasionally poetic subjectivity that reaches deeper than social realism ever could. Leaf’s willingness to resist conforming to established motifs on her first film marks her as someone to watch. Earth Mama is an expansion of themes explored in Leaf’s 29-minute documentary The Heart Still Hums, which she co-directed with Taylor Russell (from last year’s Bones and All). The short showcases five women grappling with motherhood, homelessness, and drug addiction in the child welfare system. And while some traces of her documentary source remain here, Leaf takes the material in a more meditative direction.

The first-time director works with a first-time actor in Tia Nomore, who plays the 24-year-old Gia (whose name means “God’s gracious gift”). Leaf scouted Nomore, well known in the San Francisco Bay Area’s freestyle rap battle arena, and learned she had undergone training to become a doula. Nomore’s background aligns with her role more than Leaf’s does since the filmmaker has an unlikely history in Olympic volleyball. Nevertheless, after studying photography, shooting music videos for Common and Gary Clark, Jr., and making several short films, Leaf’s directorial career has taken off nicely. Earth Mama debuted at Sundance to rave reviews and was acquired by A24, meaning it’s likely to be seen by an audience accustomed to visually distinct and director-driven projects. Indeed, the film has the imprint of a filmmaker willing to experiment, occasionally delivering surreal, albeit highly interpretable images that add expressiveness to the otherwise stifling dose of reality.

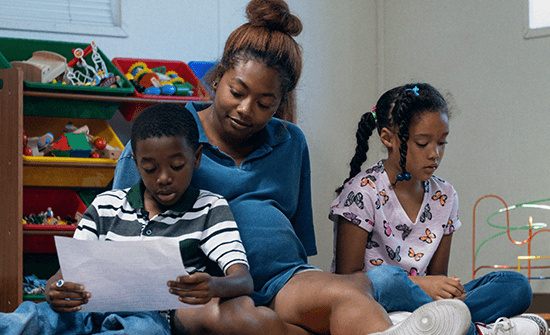

Earth Mama opens with scenes from a court-ordered group therapy for mothers with children in foster care. Each member takes turns sharing aspects of their story, how they came from troubled homes, how their parents were bad examples, and how they took those socially learned behaviors and may have passed them down to their children. In each case, the woman feels alone and trapped. They’re self-described broken people, consistently let down by their own parents and a system that views them as practically subhuman. Who can they trust? Erika Alexander plays a social worker, Miss Carmen, who oversees the group. She seems kindly and less abrasive than the other social workers in the film, and she tries to help the 37-week pregnant Gia to gain better access to her two children, Trey (Ca’Ron Jaden Coleman), who misses his mother, and Shaynah (Alexis Rivas), who won’t speak to her. There’s no mention of who fathered Gia’s children and whether he’s a source of help, but that may be because Leaf never knew her father. Even so, Miss Carmen gently pressures Gia to consider an open adoption for her unborn child, with a warm family who can’t have children of their own. Miss Carmen seems like a friend, but she’s also angling.

Of course, Gia doesn’t want to give up her baby. But with her lowly job at a photo shop, bills piling up, a prepaid phone with mere minutes left, and two other children to care for once she proves to the court she’s responsible enough, Gia doesn’t feel she has a choice. Her friend Trina (the rapper Doechii, in another first-time performance) wants her to keep the baby at all costs, but her biblical reasoning isn’t convincing Gia. Nomore’s performance, wooden only in a single scene when she’s thrust into a pushing match, relies on an inwardness that pulls away from the world. The performance recalls those of Anna Diop in Nikyatu Jusu’s Nanny or Guslagie Malanda in Alice Diop’s Saint Omer, both from last year. These films consider Black women subjected to the views of white-dominated worlds and ostracized because they don’t fit into narrowly schematized definitions, so they withdraw. Nomore shines in conveying Gia’s refusal to trust and fear of the unexpected. So much has gone wrong in her life that she latches on to any situation she can control, even if it means a sacrifice she doesn’t want to make.

Of course, Gia doesn’t want to give up her baby. But with her lowly job at a photo shop, bills piling up, a prepaid phone with mere minutes left, and two other children to care for once she proves to the court she’s responsible enough, Gia doesn’t feel she has a choice. Her friend Trina (the rapper Doechii, in another first-time performance) wants her to keep the baby at all costs, but her biblical reasoning isn’t convincing Gia. Nomore’s performance, wooden only in a single scene when she’s thrust into a pushing match, relies on an inwardness that pulls away from the world. The performance recalls those of Anna Diop in Nikyatu Jusu’s Nanny or Guslagie Malanda in Alice Diop’s Saint Omer, both from last year. These films consider Black women subjected to the views of white-dominated worlds and ostracized because they don’t fit into narrowly schematized definitions, so they withdraw. Nomore shines in conveying Gia’s refusal to trust and fear of the unexpected. So much has gone wrong in her life that she latches on to any situation she can control, even if it means a sacrifice she doesn’t want to make.

The storytelling’s measured authenticity resides in its portrait of a child protective services that dehumanizes people by taking their children away, only to put them through invasive circumstances that leave them traumatized—a theme found in this year’s A Thousand and One, except without the narrative twist that derailed the message in that example. The other women in Gia’s group, often shot in tableau-like testimonials, address the long and aching process of healing and overcoming substance abuse. And while cinematographer Jody Lee Lipes’ 16mm lensing occasionally touches on gritty realism, the camerawork also recalls the slow zoom-ins and zoom-outs of Barry Lyndon (1975), as though portraitizing an alternative subject in Gia. The film further distinguishes itself with forest imagery representing motherhood or a nightmare scene in the mirror when Gia pulls her child’s umbilical cord out of her belly button. Along with Kelsey Lu’s tonal score, these dreamt moments have an uncanny and transfixing quality, even if they don’t amount to any resolution for Gia.

Whether Earth Mama is likely to incite change in the systemic problems on display remains debatable. Fortunately, Leaf doesn’t seem concerned with such matters directly and avoids turning her film into a preachy call to action. Rather, affecting change seems less the intention than creating empathy for Black mothers like Gia, whom the system expects to fail and therein fails her. Caught in an unforgiving Catch-22, Gia is pushed and pulled, often left with few choices of her own. At my screening, members of Village Arms, a Minnesota nonprofit devoted to combating racial disparities in the entire child protection system, were there to attest to the film’s authenticity, aside from a few details here and there. Still, one of them described the film as “trauma porn.” How tragic that the film portrays Black women such as Gia in a manner that could be described this way, yet the portrait also happens to be mostly accurate.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review