Eagle Eye

By Brian Eggert |

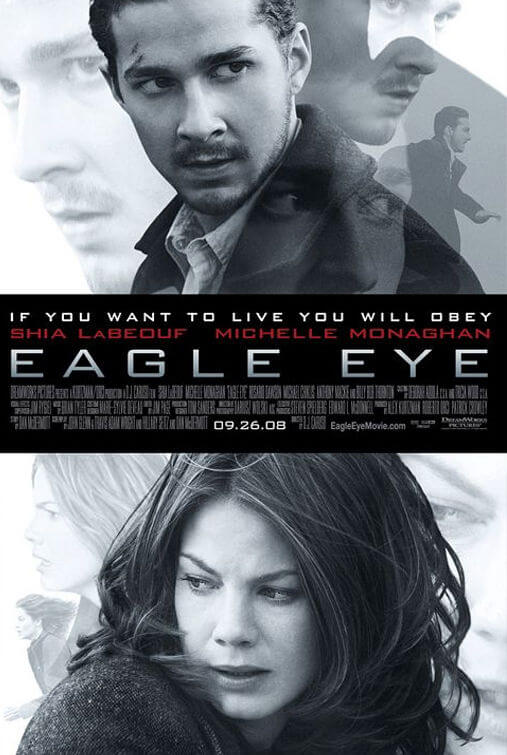

Eagle Eye begins with an intriguing premise that gets sillier and sillier as the film progresses. Producing a series of outlandish chase scenes, absurd plot twists, and constant action, all populated by one-note characters and leading to an inevitably unsatisfactory disclosure, the film requires viewers to upgrade their brains with the latest blockbuster-ready version of Suspension of Disbelief. Without it, don’t bother. Conditional to enjoying an illogical thriller such as this are likable stars, individual sequences of expertly constructed suspense, and, at the very least, some order of plausibility. This film adheres at least to the first requirement, as Shia LaBeouf reteams with his Disturbia director D.J. Caruso. LaBeouf plays Jerry Shaw, a copy-boy who checks the balance on his bank account to find $750,000 was mysteriously deposited. He returns to his apartment, where he discovers a terrorist’s cache of weapons and bomb-making supplies. Suddenly, he receives a telephone call with a woman’s voice telling him to run, that the FBI will break down his door in 30 seconds. He doesn’t. They do.

Single mother Rachel Holloman (Michelle Monaghan) gets a similar call from the same voice, warning that unless she does what she’s instructed to do, the train carrying her son to his band concert in Washington, D.C., will be derailed. The voice guides Rachel and Jerry to meet up with each other, the latter sprung from FBI custody. Together, they maneuver a series of incidents wherein every electronic device is controlled by whoever has been calling them. Traffic lights change color, onboard navigational systems suddenly speak, and crane arms smash pursuing police cars. The wild goose chase for who-knows-what should permit LaBeouf and Monaghan to display their respective charms, but they remain paper-thin characters we’re neither invested in nor particularly care about. The most we can say about them is that we’d prefer they didn’t die. On their tail are oblivious agents played by Billy Bob Thornton and Rosario Dawson, both after the same framed fugitive, both on autopilot as the script insists. None of these characters are given any depth, and the film suffers for it.

I’m baffled as to how there can be so much homage to Alfred Hitchcock in one film without an inkling of his associated suspense. There’s the North by Northwest setup featuring The Wrong Man sent across the country, even to an abandoned field (sans crop duster), at the whim of unseen bad guys. There’s the meet-cute device used in several Hitchcock pictures such as The 39 Steps and Saboteur, virtually hand-cuffing a man and woman together through a series of events, at the end of which they fall in love. And there’s the concert finale from The Man Who Knew Too Much, whereupon if a single note is played, a political assassination is carried out. Steven Spielberg already dug himself into a hole with Disturbia, the previous collaboration between Caruso, LaBeouf, and the executive producer that blatantly modernized the outline of Rear Window without giving due credit. Now there’s a pending lawsuit. Though I doubt anyone could make a case for Eagle Eye in court, the evidence is there, just hidden under the guise of up-to-date technology. (Note: Lawyers for The Kubrick Estate might want to look into the film’s reproduction of Hal 9000.)

Enjoying the outcome is not merely about overlooking the blatant thievery from Hitchcock or enduring impossibly elaborate circumstances but tolerating over-edited action scenes. Every vehicle imaginable, from automobiles to airplanes to a trash barge, is used in the chase, supplied for the audience in brief millisecond cuts as they’re tossed about the screen. Taking lessons learned from The Michael Bay School of Filmmaking, Caruso’s bland action is left without much clarity thanks to the mind-numbing hack-and-slash job in the edit. Shoved down our throats in the last moments, a film’s message warns us to watch out for Big Brother’s burgeoning power, something better discussed in Eagle Eye’s older and more likable brother, Enemy of the State, or even, heaven forbid, George Orwell’s original text. The postscript commentary might suggest an ulterior motive beyond just supplying diversion for two hours, but it’s a forced moment in a film otherwise exclusively about fast editing and silly plot developments. For the majority, some may be able to pull the plug on their sense of logic and enjoy the procession of inanity, but when it’s all over, the result isn’t nearly as interesting or as clever as it could be.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review