Duplicity

By Brian Eggert |

Tony Gilroy uses star power to sell his films, to get audiences in the theater where they discover the outcome is propelled by something entirely different. When he wrote and directed Michael Clayton, audiences flocked to their local moviehouses not because they wanted to see a character study about conscience or a morality play about inner discord, but rather because George Clooney starred. Word-of-mouth spread, informing everyone that, indeed, Clooney was superb in his role but also that the attached film boasted grave drama, staggeringly good performances by Tom Wilkinson and Tilda Swinton, and an affecting purpose beyond sheer amusement. It became one of the best pictures of 2007.

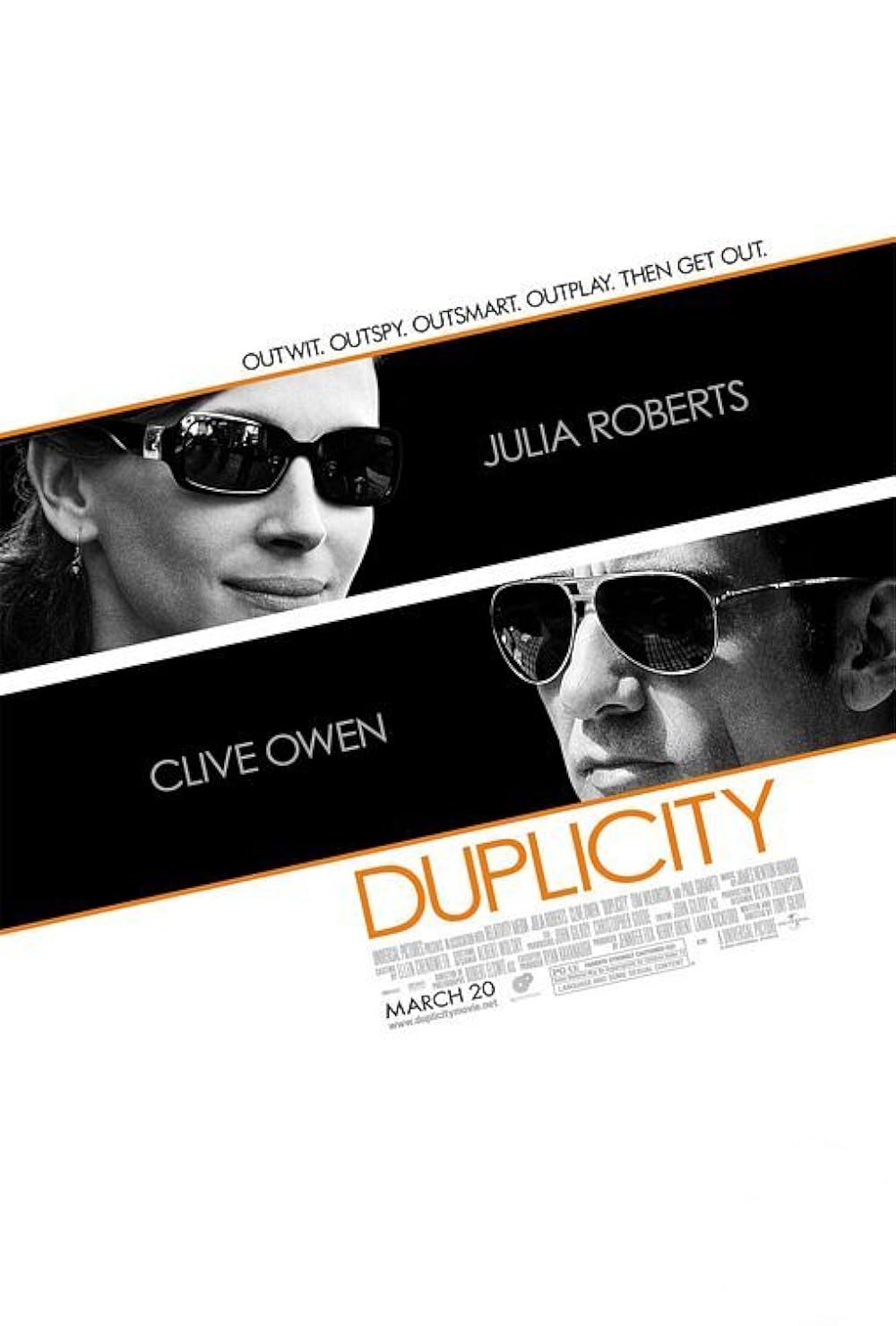

He’s attracted us the same way with Duplicity. Sold as a romantic spy comedy in pure Hollywood style, the trailers and posters feature lots of laughing and embracing between its two stars. But instead of two hours of merry frivolities featuring Julia Roberts and Clive Owen, Gilroy constructs a rather clever espionage tale, which permeates with likable characters and a smart, twisting story. In the cinematic tradition of Charade and To Catch a Thief, the film places two celebrities in exotic locales around the world, everywhere from Rome to Zurich, shakes up their experience with fitting intrigue, and lets the yarn unravel. Roberts plays ex-CIA agent Claire Stenwick. Owen plays MI6 field agent Ray Koval. Both have been trained to instinctually suspect and deceive everyone. When they eventually meet and fall for each other, the normal doubts and insecurities of a relationship are on overdrive, as each uses their special skills to outwit the other.

At the center of the film, however, resides a corporate competition between two major companies. Rival CEOs Howard Tully (Tom Wilkinson) and Richard Garsik (Paul Giamatti) like to play dirty, stealing the other’s secrets via “Moscow Rules” espionage, counterintelligence, sabotage, and surveillance. The entire film is punctuated by the slow-mo title sequence, during which the two executives battle it out with hilariously sloppy jabs and a kick to the shin. As pathetic as their physical statures may be, their game is ruthless. Viewers would do well to remember that Duplicity has just as much to offer by way of big-business wars as it does the superfluous rom-com stylings fans of Roberts’ filmography are accustomed to.

Told using periodic flashbacks that inform the motivations of the players in the present, Gilory cons his viewers using a puzzle-piece structure and oodles of dramatic irony. Claire and Ray go undercover as internal security officers to expose a new company product being developed under top-secret supervision. When they can safely steal the film’s McGuffin, they’ll sell it for millions, live the sweet life in hotels, order room service, and make love. That’s the plan, anyway. Neither trusts the other, not completely, but that’s their nature as spies, and since each understands that nature, they’re more apt to appreciate that deceptive characteristic in the other.

To say anything more detailed would ruin the fun. It’s enough to know that Roberts and Owen make a fine onscreen couple, and both fall into the role of commercial spy without much effort. Owen was born to play debonair, whereas Roberts, whose work has never reached above just endurable, succeeds in being not annoying, even likable. Perhaps she has moved passed the days of cheesy and problematic affairs with Richard Gere and has blossomed into a respectable actress. Time will tell. But speaking Gilroy’s expertly written dialogue makes them all the more engaging as movie stars, retaining the film’s Hollywood appeal.

Unlike Gilroy’s action-laden scripts for the three Bourne movies, Duplicity relies on the strength of his expert scenario and lively dialogue, versus concentration on bravado fights set to thumping techno music. It’s a genre-bending film, being part dry corporate satire, part espionage thriller, and part rom-com, complete with a high-stakes “meet cute” device and ensuing sharp discourse to follow. We’re unsure if the romantic portions are meant to enlighten the corporate satire or vice-versa, leaving us to discover in the end that both driving arcs are complimentary and work out in a uniquely pleasant way for all parties. That Gilroy refuses to limit the story to just one focus in desire for something more intricate makes his film complex while also being a light, entertaining treat.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review