Dune: Part Two

By Brian Eggert |

“Our plans are measured in centuries.”

—Reverend Mother Mohiam, Truthsayer to the Emperor of the Known Universe

Denis Villeneuve has made something extraordinary with Dune: Part Two and its predecessor. Adapting the 1965 novel to the screen, Villeneuve turns Frank Herbert’s ideas and characters into visionary cinema. Beyond tapping into the source material’s vast potential for emotion and sociopolitical commentary, which he does with a careful hand and sharp detail, the director of Arrival (2016) and Blade Runner 2049 (2017) applies a formal bravado and seriousness found in history’s most substantial works of science fiction. To say the filmmaker made good on the promise of the first part from 2021 is an understatement. Both films are exceptional in their own ways, but they become something altogether more when considered together—among the most satisfying and accomplished science-fiction series in recent memory. Not only do they supply an epic-sized spectacle with action and awing sights, but they also remark on political occupation, genocide, the battle for natural resources, and religion as a means of control. While it could have been a typical retread of Star Wars in a lesser director’s hands, Villeneuve’s version takes a galactic view to consider the broader implications. It’s less about rooting for a hero than watching an elaborate strategy unfold. Dune: Part Two is rich with emotion, intellect, and cinematic ambition, delivering at heights few Hollywood productions have achieved.

On a personal level, I breathed a sigh of relief after the final frame. I’ve admired Herbert’s book since my teens and have never had faith that any screen adaptation could do the material justice. Look at the precedents: David Lynch’s 1984 feature boasted some incredible imagery and a worthy cast; however, between the director’s loss of creative control and admitted distance from the material, Lynch’s version doesn’t click. The Sci-Fi Channel miniseries from 2000 has other problems, ranging from its lack of faithfulness to the book to its underwhelming production values. Not even Alejandro Jodorowsky’s unmade version of Dune, detailed in the 2013 documentary, sounded inspiring since the filmmaker seemed more interested in extravagances than Herbert’s themes. Still, when Villeneuve’s first part was released in 2021, the sequel had not yet been greenlit. I approached with perhaps too much caution, not wanting to invest myself or build expectations should the sequel go unmade or not stick the landing. Watching the second half, all of my concerns faded away, and I found myself immersed in Herbert’s world again, seeing moments from the book onscreen just as my mind’s eye had seen them as a reader. That’s just one aspect of Villeneuve’s genius—his ability to conjure images from the text and visualize what Herbert wrote.

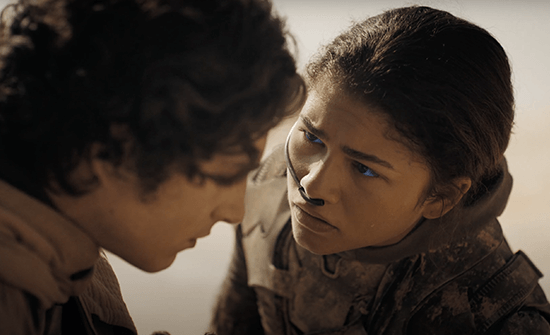

And similar to Herbert’s book, Villeneuve’s version considers the transfer of power from an almost critical distance. Although it’s tempting to view Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet, excellent), the messiah of the Fremen desert people, through the lens of the traditional hero’s journey—the monomyth narrative pattern written about in Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949)—it’s perhaps more rewarding to view the events with a Bene Gesserit perspective. In other words, not from the subjective perspective of Paul’s rise to power and fulfillment of prophecy, becoming what the so-called witches deem the Kwisatz Haderach or Muad’Dib as the Fremen know him. Paul goes by many names and titles, but his rebellion on Arrakis and the subsequent seizing of the Emperor’s throne feel like chess moves in a larger game. The screenplay by Villeneuve and Jon Spaihts considers a long line of maneuvers, so while the audience hopes for Paul to rise, there’s an underlying sense that he is less a hero than another ruler, exploiter, and political force using religion as a means to acquire power. Yet, the affecting and ultimately judgmental eye of his lover, Chani (Zendaya), earns the most sympathy. Still, as Charlotte Rampling’s Truthsayer observes, “There are no sides.”

If not already apparent, it’s best to watch the 2021 film before Part Two and catch up on the elaborate mythology. There’s no recap or “previously on” summary here; the sequel picks up where the first part ended. After his family, House Atreides, falls to the biomechanical House Harkonnen, the returning brute custodians of Arrakis, Paul joins the Fremen to earn the desert people’s loyalty. Paul has slain a Fremen warrior to prove himself, buying time for him and his Bene Gesserit mother, Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson). Among the Fremen, Stilgar (Javier Bardem) and many others believe Paul is the “the One”—the Lisan al-Gaib, or off-world prophet. Others have their doubts. But Jessica, pregnant with a baby who communicates with her telepathically, sets out to become the Reverend Mother of the Fremen—a process that requires her to drink poison yet imbues her with all the memories of her forbearers. By acquiring this position, she hopes to convince them that her son is their promised messiah, who will return the trees and liberate the arid planet. Paul gradually fulfills one prophecy after another, survives trial after perilous trial, amasses a deadly arsenal, and converts dissenters to followers. Among them is Chani, who comes to respect Paul and becomes his lover.

If not already apparent, it’s best to watch the 2021 film before Part Two and catch up on the elaborate mythology. There’s no recap or “previously on” summary here; the sequel picks up where the first part ended. After his family, House Atreides, falls to the biomechanical House Harkonnen, the returning brute custodians of Arrakis, Paul joins the Fremen to earn the desert people’s loyalty. Paul has slain a Fremen warrior to prove himself, buying time for him and his Bene Gesserit mother, Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson). Among the Fremen, Stilgar (Javier Bardem) and many others believe Paul is the “the One”—the Lisan al-Gaib, or off-world prophet. Others have their doubts. But Jessica, pregnant with a baby who communicates with her telepathically, sets out to become the Reverend Mother of the Fremen—a process that requires her to drink poison yet imbues her with all the memories of her forbearers. By acquiring this position, she hopes to convince them that her son is their promised messiah, who will return the trees and liberate the arid planet. Paul gradually fulfills one prophecy after another, survives trial after perilous trial, amasses a deadly arsenal, and converts dissenters to followers. Among them is Chani, who comes to respect Paul and becomes his lover.

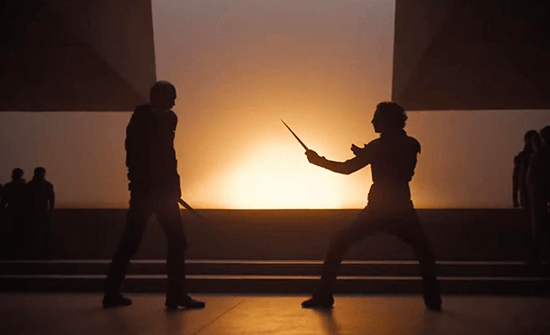

However, Chani isn’t quite prepared for how Paul intends to seize power and get revenge on the Emperor of the Known Universe (Christopher Walken)—by disrupting the Harkonnens’ Spice-mining operations, inciting a holy war among the Empire’s many houses, and ascending in the chaos. All of this fuss is over Spice, the speckled fragments in the desert that, when used as a psychotropic, opens the mind and facilitates space travel, making it the most coveted resource in the universe. “Power over Spice is power over all,” crackles a voice from the void before the Warner Bros. logo, reminding us that the characters in Dune, like those in Game of Thrones, serve as pawns amid power plays. Take the Emperor’s daughter, Princess Irulan (Florence Pugh), who, along with her fellow Bene Gesserit, Lady Margot Fenring (Léa Seydoux) and the Truthsayer, anticipate the Emperor’s fall. But to whom? Paul could prove victorious. Then again, so could the Harkonnen—not Glossu Rabban (Dave Bautista), the Baron’s (Stellan Skarsgård) nephew who has lost control of Arrakis to Paul’s Fremen rebellion. It’s more likely the Baron’s other nephew, Feyd-Rautha (Austin Butler, convincingly replicating Skarsgård’s accent). Lady Margot moves the Feyd-Rautha piece into place despite believing him psychotic, which he is, and ensures his bloodline should he prove victorious against Paul.

While the Dune saga might play like a space opera at times, with pregnancies and revelations about Paul and Jessica’s true bloodline, Villeneuve embraces Herbert’s themes about religion as an exploitable belief system to serve political gain. The book and film draw from humanity’s historical struggles over resources such as oil and land, with parallels between Paul’s adoption of the Fremens’ ways and T. E. Lawrence’s immersion into the Arab Rebellion during the First World War. Villeneuve has announced his desire to adapt Herbert’s second novel in the series, Dune Messiah, which continues the trend of watching vast political and religious regimes rise and fall. Such themes have made the book an enduring text for scholarly analysis, illustrating how politics adopt religious concepts to secure control—notions all too familiar in a country where Christian nationalism has become a platform for certain leaders. However, with the Fremen, the themes in Dune reach even further into social foundations built on the concept of personal discipline for the community good, which Herbert drew from Islamic values. Through that lens, Paul becomes less a hero than a warning about “chosen ones” who buy into their own savior myth.

This is all to say that Dune is a multifaceted work brimming with ideas. With a few exceptions, Villeneuve and Spaihts have adapted the material with faithfulness in mind. If only to maintain a commercially viable PG-13 rating, scenes of Baron Harkonnen and Feyd-Rautha’s predatory sexual behavior have been omitted from the page-to-screen translation, robbing the characters of a particularly nasty detail to their monstrosity. But in most other instances, the filmmakers have preserved the tone and spirit of Herbert’s text. To be sure, Villeneuve finds inspired ways of realizing facets of the story, such as Paul’s haunted dreams of millions dying under his reign and the elegant depiction of gravity-less Harkonnen gliding up a rock face or dropping from an aircraft. Shots from inside of Jessica’s womb of the unborn Alia, who talks to her mother and has an uncanny knowledge of everything happening, recall the all-seeing view of the Star Child from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)—and they have an analogous metaphysical quality to them. But even with imagery such as Alia in the womb drawing from the Star Child, Villeneuve’s filmmaking doesn’t feel like anyone else’s, which is a rarity among today’s directors.

This is all to say that Dune is a multifaceted work brimming with ideas. With a few exceptions, Villeneuve and Spaihts have adapted the material with faithfulness in mind. If only to maintain a commercially viable PG-13 rating, scenes of Baron Harkonnen and Feyd-Rautha’s predatory sexual behavior have been omitted from the page-to-screen translation, robbing the characters of a particularly nasty detail to their monstrosity. But in most other instances, the filmmakers have preserved the tone and spirit of Herbert’s text. To be sure, Villeneuve finds inspired ways of realizing facets of the story, such as Paul’s haunted dreams of millions dying under his reign and the elegant depiction of gravity-less Harkonnen gliding up a rock face or dropping from an aircraft. Shots from inside of Jessica’s womb of the unborn Alia, who talks to her mother and has an uncanny knowledge of everything happening, recall the all-seeing view of the Star Child from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)—and they have an analogous metaphysical quality to them. But even with imagery such as Alia in the womb drawing from the Star Child, Villeneuve’s filmmaking doesn’t feel like anyone else’s, which is a rarity among today’s directors.

Villeneuve isn’t making a pastiche or compendium of allusions to other films; rather, he carves out something singular with Dune and its sequel, adding to his already impressive work in science fiction. On a purely technical level, Part Two is astounding. Production designer Patrice Vermette and costumer Jacqueline West return from Dune, creating spaces and outfits that look wholly original. At the same time, cinematographer Greig Fraser balances scopic, severe sequences with more spontaneous interpersonal moments. And while CGI accomplishes much of Villeneuve’s vision, there’s not an oppressive computerized quality to everything onscreen, unlike most contemporary blockbusters—even when the enormous sandworms arrive onscreen, their mouths vaguely resembling the human eye. Villeneuve shot many of the exteriors in Abu Dhabi and Jordan, but other sequences rely on CGI. A black-and-white sequence under the black sun of Giedi Prime, the Harkonnen home planet, delivers a convincing arena with special effects. Not even Hans Zimmer’s music reverberating through the viewer’s chest feels like the typical Hollywood score; it’s otherworldly and hypnotic, yet it supports the thrilling aspects of the story with guitar riffs. Most of these technical areas earned the 2021 film its six Oscar wins, and the sequel deserves the same attention. It’s also worth noting how the stellar cast, one of the most stacked ensembles in recent film history, disappears into their roles effortlessly, thanks to the strength of Villeneuve’s storytelling.

Dune: Part Two further proves that a popcorn-munching, $150-million-plus production doesn’t need to be mindless entertainment; rather, it can be cerebral, passionate, and challenging. Villeneuve already proved as much with Dune—not to mention Arrival and Blade Runner 2049. He doubles down with the sequel, which may shock viewers who expect to follow Paul on a heroic rise to power. The audience may root for Paul at the moment because the Harkonnen look like an awful alternative. But is Paul any better? Through Chani’s eyes, who knows Paul’s doubts and strategy more intimately than anyone, except perhaps Jessica, she sees the opportunism and scheming by the proposed leader, who so shrewdly chose the name Muad’Dib after a spry kangaroo mouse that can make its own water. But Chani sees through all that. “You want to control people? Tell them a messiah will come. They’ll wait for centuries,” she tells him early on. The Bene Gesserit know this to be true; so does Paul, yet he cannot help but follow the path laid out for him. As I grappled with these ideas after the sequel, I must acknowledge my complete immersion into the film’s world; I was engaged on every level. Fitting, for what must be one of the greatest science-fiction epics of all time.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review