Dune

By Brian Eggert |

Near the end of Denis Villeneuve’s Dune, there’s a brief moment where our hero, Paul Atreides, played by Timothée Chalamet, sees a small rodent scurrying on the sand. Paul notices how the creature’s large ears accumulate moisture into a droplet, which it uses to sustain itself under the harsh desert conditions. Sometime later, hopefully, we will see Paul name himself muad’dib after the rodent when he leads the Fremen, the nomadic people of Arrakis. But unless you’ve read Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel—or the Wikipedia summary, as people find the book difficult to finish—the significance of this moment may elude you. And yet, Villeneuve and his co-writers Eric Roth and Jon Spaihts included the scene in their adaptation. Their devotion to Herbert’s text captures his layered investigation of imperialism, Middle-Eastern culture, ecology, industry, patriarchy and matriarchy, and political strategy in fine detail. Tackling source material considered unfilmable by some, Villeneuve leaves no theme untapped and does what seemed impossible by capturing the book’s depth in a major motion picture. It’s a perfectly cast and handsomely designed production, full of incredible sights. But given that Dune represents only half of Herbert’s story, the other half of which remains to be filmed or even greenlit at the time of this review, we’re left to wonder whether Chalamet will ever become muad’dib.

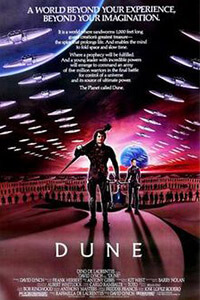

The latest attempt to bring Herbert’s tome to the big screen shares in a history of troubled adaptations. Chilean filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky first tried in the mid-1970s, assembling artists like Moebius, H.R. Giger, and Chris Foss to create elaborate designs for a proposed 12-hour film that was never to be. David Lynch completed a screen version released in 1984, but he lost control to producer Dino de Laurentiis. Even if Jodorowsky or Lynch had been given limitless funds and creative freedom to complete their adaptations, the resulting films wouldn’t have been true to Herbert’s book. Both directors intended to explore aspects that interested them most. Jodorowsky seemed more driven by the potential for avant-garde filmmaking techniques and psychedelic artifice than doing the material justice. However, Lynch’s take, while beautifully staged, reduced the story to its roots in Joseph Campbell’s monomyth, developing the idea of Paul’s dreams leading to his emergence as a hero. Villeneuve is more selfless than his predecessors; he applies his aesthetic of lingering camerawork and mesmerizing visuals to serve Herbert’s vision, crafting a faithful translation.

But Dune’s long-awaited release comes with a few caveats. There’s no guarantee that Villeneuve’s 155-minute, $165 million feature will earn a sequel for starters. The production company chose not to gamble on the film’s success, creating a situation that could result in disaster if the box-office numbers disappoint and Villeneuve never gets to make the second half. After delays due to the pandemic and a release plan that finds the film in both theaters and HBOMax on the same day, the chance of Dune earning record-breaking receipts seems unlikely. These ideas scratched at the back of my mind while watching the film on opening night. There’s a sense of anxiety that the narratively incomplete story will never reach screens, and admittedly, this critic felt somewhat preoccupied with such thoughts. What’s more, Herbert’s novel does not lend itself to two halves, meaning Dune feels dramatically unsatisfying and incomplete, and its characters do not grow because the story ends before they can. It’s not like watching an individual Star Wars episode or Lord of the Rings chapter that, despite the potential for a cliffhanger, nonetheless has a beginning, middle, and end. There’s a nagging feeling that any assessment of Dune will remain somehow deficient until it can be viewed with its concluding part.

But Dune’s long-awaited release comes with a few caveats. There’s no guarantee that Villeneuve’s 155-minute, $165 million feature will earn a sequel for starters. The production company chose not to gamble on the film’s success, creating a situation that could result in disaster if the box-office numbers disappoint and Villeneuve never gets to make the second half. After delays due to the pandemic and a release plan that finds the film in both theaters and HBOMax on the same day, the chance of Dune earning record-breaking receipts seems unlikely. These ideas scratched at the back of my mind while watching the film on opening night. There’s a sense of anxiety that the narratively incomplete story will never reach screens, and admittedly, this critic felt somewhat preoccupied with such thoughts. What’s more, Herbert’s novel does not lend itself to two halves, meaning Dune feels dramatically unsatisfying and incomplete, and its characters do not grow because the story ends before they can. It’s not like watching an individual Star Wars episode or Lord of the Rings chapter that, despite the potential for a cliffhanger, nonetheless has a beginning, middle, and end. There’s a nagging feeling that any assessment of Dune will remain somehow deficient until it can be viewed with its concluding part.

Writing this review, then, becomes a tricky task. For one, I cannot ignore that feeling of emptiness that Dune left me with when the credits began to roll. Should the film be blamed for this, or is that just the nature of this particular beast? Also, I cannot ignore everything I felt before that emptiness took over. Villeneuve does something incredible by visualizing certain scenes and characters the way I envisioned them when reading the book, which I cherish. Few science-fiction films have realized their source material so well (so far, anyway). The director, cinematographer Greig Fraser, and production designer Patrice Vermette render distinct worlds that reflect the story’s setting of several thousands of years in the future. The production resists the ostentation of Lynch’s version, preferring an elegant functionality to the costumes, sets, vehicles, and planetary designs. Yet, we see familiar sights, suggesting they originated from the unmentioned Earth. Small details such as bullfighting and bagpipes appear around the Atreides family, who hail from the ocean planet Caladan but have been tasked with overseeing Arrakis, a planet that produces “spice” needed for intergalactic travel—it also opens the mind and extends life. The Fremen, clearly drawn from Islamic and Middle-Eastern cultures, have a familiar spirituality that attracts Paul, recalling the titular enigma in Lawrence of Arabia (1962). The film’s best scenes involve the curt Stilgar (Javier Bardem), whose social graces confound most members of House Atreides.

The story of Dune also remains true to the book, although the script makes slight alterations to enhance the depth of certain characters. Paul, of course, has more personality thanks to Chalamet’s slender frame, inwardness, and vulnerable gestures. His chummy relationship with his mentors, Duncan Idaho (Jason Momoa) and Gurney Halleck (Josh Brolin), prove alternately endearing and parental. Oscar Isaac, too, brings a great deal of humanity to Paul’s father, Duke Leto, whose otherwise noble eyes also contain a parent’s unwavering love. The screenplay’s best alteration builds upon Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson), Paul’s mother and member of the Bene Gesserit—a group of powerful women who work in secret to shift power in the universe away from the unseen Emperor. Through haunting sound design and flashes of dream imagery laden with blood and fire, Paul hears the whispers of the Bene Gesserit and sees glimpses of his future path as a revolutionary alongside the Fremen woman Chani (Zendaya). Jessica hints that his future with the Fremen will “bridge space and time, past and future.” All of this talk of emergence and fate on a desert planet, and the viewer will begin to realize just how much George Lucas lifted from Herbert to write Star Wars (1977).

The film efficiently lays out its complex story, offering only a few clunky scenes of exposition by way of Paul’s informative holographic lessons. Otherwise, the plot is easy enough to follow—more manageable than the often dense book. Duke Leto takes over Arrakis from the overfed, spineless, and hovering monster Baron Harkonnen (Stellan Skarsgård), who has arranged to retake the planet and kill the Atreides clan with the secret approval of the Emperor of the Known Universe. When the Harkonnen retake Arrakis and wipe out most of Duke Leto’s forces, the sweeping sequence of fighting and explosions is quite appropriately not a hunk of thrilling action. Refreshingly, Dune is not escapism. Instead, Villeneuve fills us with dread, signaled by sublime and horrific fires that consume the night’s sky. Paul and Jessica escape the takeover with their lives and head into the desert to ally with the Fremen. The film considers these events with an intertextual richness that admirers of Herbert’s book will celebrate, leading the way for many an essay about how the film’s portrayal of women, colonized cultures, and ecocentrism, among many other lenses, comments on our contemporary world.

The film efficiently lays out its complex story, offering only a few clunky scenes of exposition by way of Paul’s informative holographic lessons. Otherwise, the plot is easy enough to follow—more manageable than the often dense book. Duke Leto takes over Arrakis from the overfed, spineless, and hovering monster Baron Harkonnen (Stellan Skarsgård), who has arranged to retake the planet and kill the Atreides clan with the secret approval of the Emperor of the Known Universe. When the Harkonnen retake Arrakis and wipe out most of Duke Leto’s forces, the sweeping sequence of fighting and explosions is quite appropriately not a hunk of thrilling action. Refreshingly, Dune is not escapism. Instead, Villeneuve fills us with dread, signaled by sublime and horrific fires that consume the night’s sky. Paul and Jessica escape the takeover with their lives and head into the desert to ally with the Fremen. The film considers these events with an intertextual richness that admirers of Herbert’s book will celebrate, leading the way for many an essay about how the film’s portrayal of women, colonized cultures, and ecocentrism, among many other lenses, comments on our contemporary world.

Still, in its current, halved form, Dune is an emotionally dissatisfying experience—mainly due to extratextual issues—albeit one that has the potential of becoming one of the greatest science-fiction films ever made. If “Part Two” happens, and it’s just as well-crafted as “Part One,” then cinephiles have a treasure awaiting them. But I feel about Dune similarly to how I felt in 2001 about The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, another open-ended chapter in a series. I recognize this film’s individual excellence, but its lasting effect may depend on what follows. At least with Peter Jackson’s trilogy, he filmed them all simultaneously, representing an enormous commitment on the part of New Line Cinema. With Dune, the studio’s commitment remains to be seen. In the meantime, Villeneuve’s treatment results in a million details that intrigue, from the way he portrays “the voice” in disorienting layers of sound to the way the mouths of Arrakis’ enormous sandworms resemble the iris of an eye. The director achieves another impressive trick by casting a roster of all-star performers who disappear entirely into their roles. Best of all, Villeneuve seems to understand the material better than any other director before him; he points every element of the cinematic apparatus toward the singular goal of realizing Herbert’s vision. It’s gratifying to see a filmmaker who understands Dune finally, but it makes my hope for a sequel even more desperate and, at this moment, worrisome.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review