Reader's Choice

Dune

By Brian Eggert |

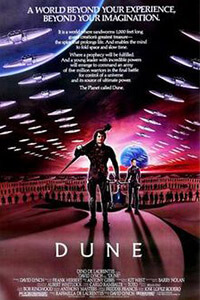

“The dream unfolds,” whispers Paul Atreides, played by Kyle MacLachlan in the 1984 adaptation of Dune. Images from Paul’s unconscious mind bleed into reality. His dreams about the desert planet Arrakis have aligned with the prophecies of the native Fremen, a nomadic underclass destined for rebellion. “The sleeper has awakened,” he will announce later. David Lynch’s film clings to this idea of an awakening compelled by mental images, excising author Frank Herbert’s entrenched interest in politics, environmental balance, world religions, historical parallelism, and gender roles for something decidedly more, well, Lynchian. Adapting the 1965 book to the screen, Lynch refines the material through a distillation of his own artistic vision, eliminating what does not interest him and reinforcing what does. But rather than dwell too much on the many potential points of contention Herbert loyalists might find in Lynch’s translation of the material, it’s impossible not to look upon Dune with admiration, albeit reticent. Working within the demands of a major blockbuster production, Lynch makes countless artistic concessions and alterations, but the resulting film is too strange and uncommon not to admire for its many erraticisms—even while this film maudit is neither a great Lynch film nor a superior representation of Herbert’s novel.

More extensive histories have been written about the production of Dune than the one I will provide. Many have noted that Lynch, fresh from his midnight madness favorite Eraserhead (1977) and breakthrough on The Elephant Man (1979), considered various offers for his next project, including a chance to direct Return of the Jedi for George Lucas or Thomas Harris’ novel The Red Dragon. It was producer Dino de Laurentiis who finally convinced the director to adapt Herbert’s book. In Lynch on Lynch, author Chris Rodley talks about how the production represented a case of “naivety meets reality” when the avant-garde auteur found himself in charge of millions in budgetary dollars, shooting in Mexico City with a cast of thousands on eight sound stages. Others have observed that Lynch, with only two films to his name and years spent struggling to get his work seen, could not resist a blockbuster-sized production, if only to prove to himself that he had finally “made it” as a filmmaker. Signing on without final-cut approval, a mistake he would never make again, Lynch later regretted the three years he spent making Dune—a year of which was spent shooting: six months on principal photography and another six months shooting special FX. “I really went pretty insane on that picture,” he told Rodley. Fortunately, the film’s critical and box-office failure meant he was spared from having to make the two sequels he had signed on to direct.

Herbert’s sprawling novel, which some find unfinishable, takes place over eight thousand years from now, during a trade dispute between three planets in an intergalactic and capitalistic network. Lynch and his production designer, Tony Masters, conceived each planet with distinct sets that look like Antoni Gaudí and H.R. Giger conspired to create something otherworldly. On Caladan, lush with water and trees, every structure has been carved out of actual wood with ornate designs that reflect its leader, the Emperor of the Known Universe (Miguel Ferrar). Giedi Prime, a black and industrial world, feels like it was built in the factories near Jack Nance’s apartment in Eraserhead; it’s all steam and metal, and it’s populated by biomechanical tyrants called the Harkonnen. The titular planet, Arrakis, is where most of the action takes place. It’s a world of sand, where enormous worms produce a mind-altering spice that allows Guild Navigators to “fold space” and travel between two points in an instant. When Lynch was writing his screenplay, he read ahead in the books, grabbing an idea from Dune Messiah where a Guild Navigator addicted to spice has mutated into a thing that appears in a giant glass case and speaks with a labial mouth. Though, there’s almost no explanation in Lynch’s script about the identity of the Guild Navigator—a “fleshy grasshopper,” as Lynch described it. This is typical of Lynch’s screenplay.

Herbert’s sprawling novel, which some find unfinishable, takes place over eight thousand years from now, during a trade dispute between three planets in an intergalactic and capitalistic network. Lynch and his production designer, Tony Masters, conceived each planet with distinct sets that look like Antoni Gaudí and H.R. Giger conspired to create something otherworldly. On Caladan, lush with water and trees, every structure has been carved out of actual wood with ornate designs that reflect its leader, the Emperor of the Known Universe (Miguel Ferrar). Giedi Prime, a black and industrial world, feels like it was built in the factories near Jack Nance’s apartment in Eraserhead; it’s all steam and metal, and it’s populated by biomechanical tyrants called the Harkonnen. The titular planet, Arrakis, is where most of the action takes place. It’s a world of sand, where enormous worms produce a mind-altering spice that allows Guild Navigators to “fold space” and travel between two points in an instant. When Lynch was writing his screenplay, he read ahead in the books, grabbing an idea from Dune Messiah where a Guild Navigator addicted to spice has mutated into a thing that appears in a giant glass case and speaks with a labial mouth. Though, there’s almost no explanation in Lynch’s script about the identity of the Guild Navigator—a “fleshy grasshopper,” as Lynch described it. This is typical of Lynch’s screenplay.

The book could be accused of too much exposition, too much detail, whereas Lynch’s film balances somewhere between over-clarifying some points and leaving others frustratingly out of reach. The film opens in the emptiness of space, where an industrial noise, once again reminiscent of Eraserhead, hums on the soundtrack. Princess Irulan (Virginia Madsen) explains about the intrigue between the three planets, and then, fading in and out for no reason whatsoever, returns to say, “Oh yes, I forgot to tell you—.” Dino and Raffaela de Laurentiis demanded that Lynch include certain elements into the production, from this explainer video reminiscent of the opening crawl in Star Wars to the gold-plated titles. Similar devices were used on de Laurentiis’ productions of Flash Gordon (1980) and Conan the Barbarian (1982), and they brand Dune with a mark of commercialism. Lynch, while conceding to such choices, lost other battles in the editing room, leaving the film without scenes necessary to understand plot points and character motivations. Princess Irulan tries to help, but she can only do so much. The extended version, which debuted on cable television in the late 1980s, offers some points of clarification, but Lynch has disowned that version and given credit to the dreaded Alan Smithee.

Paul, the prophesied messiah of Arrakis, arrives on the planet with his father, Duke Leto Atreides (Jürgen Prochnow), and his mother, Lady Jessica (Francesca Annis). The Emperor has given House Atreides the planet to manage under false pretenses; in actuality, he wants the Harkonnens, led by Baron Vladimir (Kenneth McMillan), to take the planet and dispose of House Atreides. Though the Harkonnens seize control as planned, killing Duke Leto—in a rushed takeover sequence—Paul and Lady Jessica escape into the desert and find the Fremen, blue-in-blue-eyed locals who control vast stores of water beneath the planet’s surface. Paul—armed with his disciplined mind, intuitive knowledge of the Fremen ways, and worm-riding skills—fulfills the local prophesy of Muad’Dib, a foretold ruler who will emancipate the Fremen and lead them to regain control of their planet. Paul serves as the resident T.E. Lawrence, with elements of Christ and the monomyth added for good measure. “The universe’s super-being,” the Fremen call him. After teaching the Fremen how to fight using sonic blasts from “weirding modules,” Paul leads a rebellion backed by mysticism and guerilla warfare, mostly seen in hastily compiled montages. He defeats his enemies and, in the final scenes, somehow compels rain clouds to form and shower the planet.

Admittedly, Dune is a better experience if viewed shortly after reading the book, just long enough to forget precise details but still retain a sense of the overall plot. With remnants of the text still fresh in mind, I could fill in the gaping plot holes. After years of watching Dune with a sense of confusion, I reread the book about six months before writing about the film, and I found the screen story easier to absorb. Still, no film should operate as a companion piece to its source novel. And so I was struck by how little the film explains certain entrenched elements of the book that nevertheless appear onscreen. The significance of Paul’s sister, Alia (Alicia Witt), a creepy little witch that speaks with an adult’s voice, goes mostly unclarified; though, her grotesque birthing sequence recalls the deformed child from Eraserhead. Lynch has said in interviews that he was drawn to “the sleeper has awakened” as a concept, and he builds this idea using dream imagery that feels reminiscent of the bookend sequences in The Elephant Man: water dripping in a black pool; an image of his future lover (Sean Young); and appearances by Feyd Rautha (Sting), his opponent in the film’s climactic scene. But the rebellion, the result of Paul’s awakening, remains limited to the film’s brief shots of random explosions and battle. Similarly, Lynch, either by choice or due to the demands of delivering a 136-minute cut, downplays the complex role women have in Herbert’s work—as powerful witches, wives, and mistresses.

Admittedly, Dune is a better experience if viewed shortly after reading the book, just long enough to forget precise details but still retain a sense of the overall plot. With remnants of the text still fresh in mind, I could fill in the gaping plot holes. After years of watching Dune with a sense of confusion, I reread the book about six months before writing about the film, and I found the screen story easier to absorb. Still, no film should operate as a companion piece to its source novel. And so I was struck by how little the film explains certain entrenched elements of the book that nevertheless appear onscreen. The significance of Paul’s sister, Alia (Alicia Witt), a creepy little witch that speaks with an adult’s voice, goes mostly unclarified; though, her grotesque birthing sequence recalls the deformed child from Eraserhead. Lynch has said in interviews that he was drawn to “the sleeper has awakened” as a concept, and he builds this idea using dream imagery that feels reminiscent of the bookend sequences in The Elephant Man: water dripping in a black pool; an image of his future lover (Sean Young); and appearances by Feyd Rautha (Sting), his opponent in the film’s climactic scene. But the rebellion, the result of Paul’s awakening, remains limited to the film’s brief shots of random explosions and battle. Similarly, Lynch, either by choice or due to the demands of delivering a 136-minute cut, downplays the complex role women have in Herbert’s work—as powerful witches, wives, and mistresses.

Lynch finds elegant answers to some problems of adaptation and clumsy solutions to others. Though most critics will tell you that voiceover is an unnecessary cinematic device, falling back on the lesson to “show don’t tell,” Lynch uses the effect to capture Herbert’s prose, which often dwells on his characters’ mental processes. The director claimed that the choice was a necessary evil to explain significant details that had been left on the cutting room floor, but the aural technique serves the material well. Whispered lines (“I will bend like a reed in the wind”) add atmosphere, whereas characters like Dean Stockwell’s duplicitous Doctor Yueh might be entirely unreadable without some voiceover exposition. Among Lynch’s least successful ideas, the film’s early computer effects render protective shields with ugly, impractical, boxy shapes that leave shielded combatants looking like two abstract geometric concepts. The coloring effect used on the Fremen to make their pupils blue also looks quite artificial. And Lynch’s treatment of Baron Harkonnen varies from inspired to absurd. A floating blob of sweaty excess, the Baron’s make-up, especially the needles going into infected pustules on his face, look effectively horrific. But his death scene—where Alia attacks him, and he screams and flails about in the air until a wall explodes, at which point he’s sucked outside and into the mouth of a sand worm—remains riotously mishandled.

At the same time, Lynch downplays the sexual undercurrent of Herbert’s book in at least one notable scene, when the Baron attacks a boy in front of several attendants. Herbert suggests the Baron and his younger nephew Feyd Rautha keep sexual slaves, and the Baron in particular preys on young boys, though the implication remains unclear in Lynch’s hands. We see the Baron snarl and grip his victim, then he pulls out a plug on the boy’s chest. Blood oozes from the hole, and the Baron caresses the boy’s face. The rest happens off-screen in an instant. Lynch cuts to the disturbed reactions of those watching. Whatever the Baron does, blood spatters on the wall. Cut back to the Baron, who has a satisfied expression on his face. Was it rape or murder? What has happened here? Using this scene as a reference, Robin Wood accused Dune of being “the most obscenely homophobic film I have ever seen,” but he may have been drawing from his knowledge of the same scene in the book. Although some moments support a queer reading—the camera lingering on Sting’s oiled-up physique or the intense embraces between Harkonnens—the required PG-13 rating doesn’t allow for the scene between the Baron and the boy to clarify its ambiguity. It might be homophobic sexual violence, or it might just be another scoop of odd Lynchisms thrown onto the pile.

To be sure, plenty about Dune feels as though Lynch’s subconscious has been cut open and spilled out onto the screen. It’s not to the extent of Eraserhead, of course, but the film contains enough weirdness to keep the devoted Lynch fan satiated, even if the director felt restricted by his Italian producers. “I kinda like to go off the track, to go off in a strange direction, but I wasn’t able to do that,” Lynch told Rodley. Several kooky Lynch-brand details would seem to prove otherwise: Watch the scene that finds Feyd Rautha walking with a hairless cat in some awful contraption, a lab rat strapped to its back. Or look at the shot that peers into a wound on Leto’s face; the opening begins to spew gas, anticipating the shot that disappears into a dismembered human ear in Blue Velvet (1986). Lynch’s curious asides—including the meme-worthy appearance of the Atreides family pug strapped to the chest of Paul’s combat trainer, Gurney Halleck, played by Patrick Stewart, who arms himself with the dog and a machine gun in battle—give Dune a distinction of sorts, but they don’t amount to a cohesive work of science-fiction. With Lynch feeling limited by his massive production and the producers trying to engineer a winner, the outcome is ungainly, if only occasionally admirable for its unconventional streak.

To be sure, plenty about Dune feels as though Lynch’s subconscious has been cut open and spilled out onto the screen. It’s not to the extent of Eraserhead, of course, but the film contains enough weirdness to keep the devoted Lynch fan satiated, even if the director felt restricted by his Italian producers. “I kinda like to go off the track, to go off in a strange direction, but I wasn’t able to do that,” Lynch told Rodley. Several kooky Lynch-brand details would seem to prove otherwise: Watch the scene that finds Feyd Rautha walking with a hairless cat in some awful contraption, a lab rat strapped to its back. Or look at the shot that peers into a wound on Leto’s face; the opening begins to spew gas, anticipating the shot that disappears into a dismembered human ear in Blue Velvet (1986). Lynch’s curious asides—including the meme-worthy appearance of the Atreides family pug strapped to the chest of Paul’s combat trainer, Gurney Halleck, played by Patrick Stewart, who arms himself with the dog and a machine gun in battle—give Dune a distinction of sorts, but they don’t amount to a cohesive work of science-fiction. With Lynch feeling limited by his massive production and the producers trying to engineer a winner, the outcome is ungainly, if only occasionally admirable for its unconventional streak.

Dune may be a beautiful and hollow mess, but the blame should not fall solely on Lynch. Di Laurentiis hired the wrong man for the job, and Lynch’s choices are not so much surprising as disappointing. Even so, Dune is ripe for cult adoration. The music by Toto and “Prophecy Theme” by Brian Eno are genuinely stirring. The elaborate sets would be impossible today, when a similar production might resemble Jupiter Ascending (2015) and render every world in CGI. Brief moments of inspiration (the shadow of a hunter-seeker crawling along the floor) and horror (everything with the Baron Harkonnen) linger in the memory. Though, the experience leaves me empty. Lynch once said that he likes to make films in America, but parts of America that the average person would not go, “into the depths of their being.” Over and over, he’s proven that his best work explores the sordid underbelly of American culture, whereas nothing about his artistic interests shows he’s capable of the world-building and intricacy required for delivering a faithful, or even cohesive, adaptation of Herbert’s richly layered text. If judged on the sets, costumes, and actors alone, a recommendation might come easier. Alas, Herbert’s book feels underserved and even dismissed by Lynch, who had neither the control nor the will to craft his Dune adaptation into a suitable alternative to the novel.

(Note: This review was selected by vote from supporters on Patreon.)

Bibliography:

Rodley, Chris (edited by). Lynch on Lynch. Revised Edition. Faber & Faber, 2005.

Woods, Paul A. Weirdsville U.S.A.: The Obsessive Universe of David Lynch. 2nd ed. Plexus, 2000.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review