Drive My Car

By Brian Eggert |

Haruki Murakami’s short story “Drive My Car,” included in his 2014 collection Men Without Women, contains a whole world of grief and human connections in around 30 pages. Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s screen adaptation hews close to the source material, though it could be accused of taking the scenic route. But its deviations supply a necessary byway that emphasizes what literature cannot accurately capture: time. Drive My Car runs just about three hours; the opening credits don’t even appear until the 45-minute mark. That’s an intentional choice by the Japanese filmmaker, who understands the experiential value of inhabiting the same space for an extended period. The effect is almost palpable between characters who share a theatrical stage or quietly ride together in a car for hours, whereas, in literature, the prose can only convey the idea of time. The implied intimacy in text form is experienced in real time as the filmmaker renders long, immersive shots of his characters sharing the same space. Granted, the film’s shots don’t last for hours, but the minutes-long takes feel like an eternity in the most rewarding ways.

Hamaguchi’s string of festival success since 2015’s Happy Hour has made him a name to watch. He’s been making features for two decades at this point, but he’s only started to emerge on the international scene recently with Asako I & II (2018) and The Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (2021). Drive My Car seems to signal his breakout moment, earning him several prizes at Cannes and many other awards from critical associations worldwide. No wonder—it’s the most engrossing and human film that I’ve seen from him so far, and its patient storytelling is only matched by its temporal scope. Expect many an essay to be written comparing the film to the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze and his concept of time-images or Paul Schrader’s views on transcendentalism. There’s a subtle but rigid formal agenda at work here, complete with unassuming camera placement, minimal score by Eiko Ishibashi, and enveloping shot lengths that might test impatient viewers. However, Hamaguchi’s interest in dramatic romances enlivens his understated aesthetic.

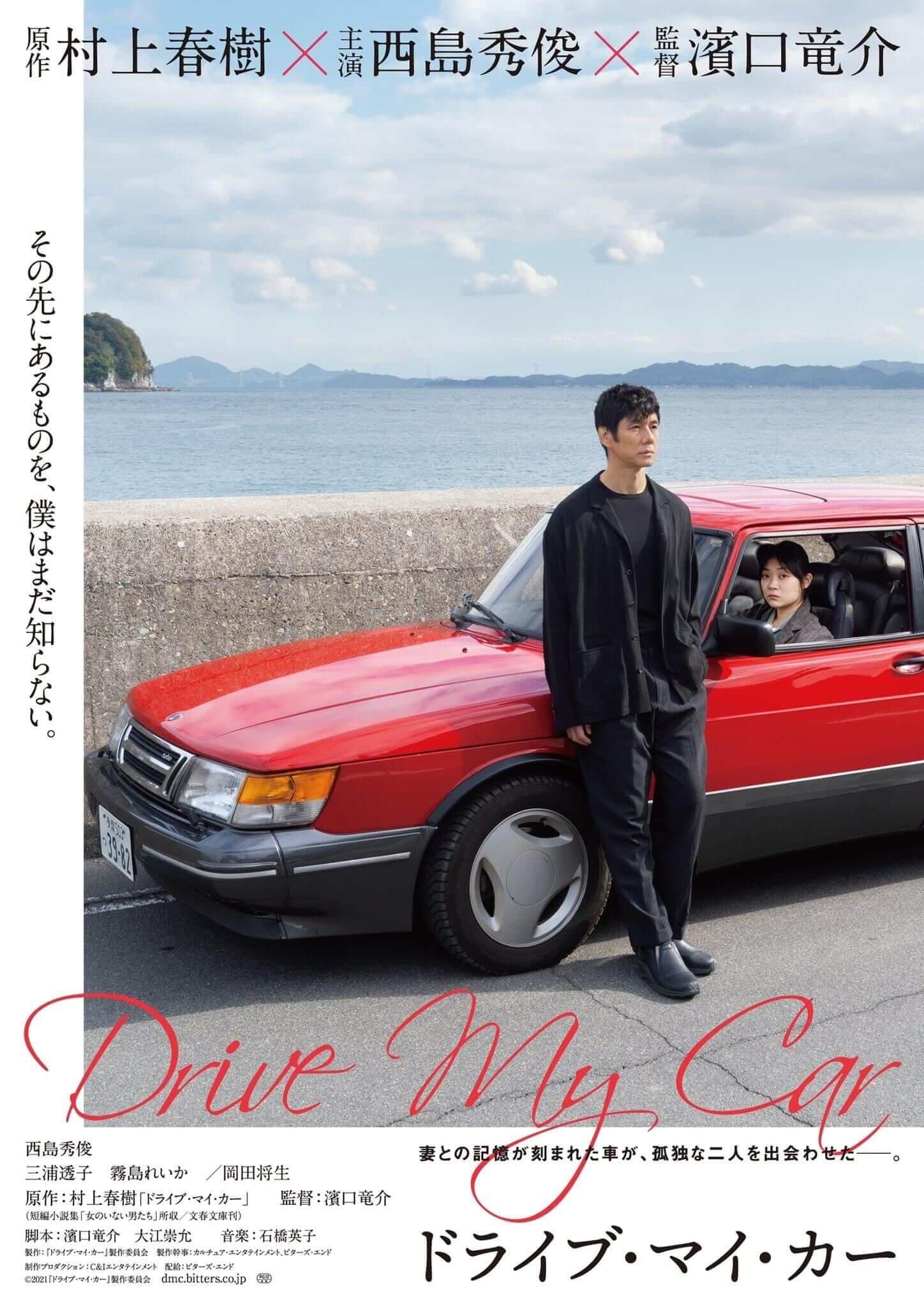

The script by Hamaguchi and co-writer Takamasa Oe opens in Tokyo, showcasing the marriage between actor and theater director Yusuke (Hidetoshi Nishijima) and screenwriter Oto (Reika Kirishima). Their relationship is complex from the start. Oto receives her best creative ideas in a trancelike state during sex, and when the actual writing begins, Yusuke helps her remember what poured out of her during the act. That’s not the only unconventional aspect of their marriage: she’s also unfaithful. She has sexual relationships with other men—a fact that Yusuke accommodates, probably because they lost a daughter some years earlier and need each other. When Yusuke drives to and from work in his red Saab (which seems to be the only red car on the road), he listens to a cassette tape Oto made for him. She reads lines from Chekov’s Uncle Vanya, leaving silences where Yusuke inserts his performance. It helps him memorize every role through dogged repetition. But returning home late one night, Yusuke finds Oto dead from a cerebral hemorrhage on the floor.

Some people may believe that time heals all wounds, but two years after Oto’s death, Yusuke still wrestles with grief and questions about the nature of his marriage. Listening to Oto’s voice on the tape each day presents a nagging reminder—especially as he performs lines about infidelity. Then, when producers ask him to mount his production of Chekhov’s play in Hiroshima, they have a strange requirement: ever since a car accident a while back, directors must be driven to and from work by the theater’s driver. Enter the twentysomething Misaki (Toko Miura), an inward and stone-faced professional who serves as his chauffeur. Though she doesn’t emerge from her shell until the film’s final third, the relationship between Yusuke and Misaki inhabits a curious, reliable, and ultimately truthful space. She waits for him during his long days of rehearsal, and when he’s ready, she delivers a smooth ride home, allowing him to focus with as much ponderousness as he requires. But what begins as discomfited silence interrupted by Oto’s voice on the cassette gradually reveals something deeper between them.

Of course, Murakami’s choice of Uncle Vanya isn’t arbitrary. Plenty of parallels exist between Chekov’s play and the characters in Drive My Car, especially in terms of acting theory. For starters, Stanislavski, who encouraged his actors to have an inner experience that would appear in their physical actions on stage, directed the play’s first production. Yusuke’s production attempts something similar through a postmodern theatrical conceit. His actors speak various languages—including Japanese, Korean, Mandarin, and Korean Sign Language—and he projects their translated dialogue onto a screen above the stage. They perform in their respective languages, requiring them to know the text so thoroughly that their responses must come from within, removing all artifice. Yusuke tells an actor that Chekov’s lines “drag the real out of you.” The same is true of the film, which finds Yusuke forced to engage with the play and his life in ways he has avoided since his wife’s death.

The play’s rehearsals lead to drama between Yusuke and the actors, including the handsome Takatsuki (Masaki Okada), a spontaneous performer who also happened to bed Oto. Although somewhat convenient in storytelling terms, Takatsuki’s presence and the conflict between him and Yusuke doesn’t go as expected, even after the director casts Takatsuki in the age-inappropriate role of Uncle Vanya—perhaps as a kind of revenge to test his wife’s lover in a role beyond his skill. Instead, the film uses Takatsuki as a fork in the road, causing Yusuke and Misaki to veer away into their own realm. Inside the intimate space of the car, they share mutual confessions that unravel the complicated people in their lives. For Yusuke, he finds a way of reconciling Oto’s behavior and their dynamic as “genuine.” For Misaki, she also learns to accept that some part of her troubled and abusive mother loved her.

Nishijima and Miura give superb performances comprised of a transfixing stillness that contrasts the onstage performances. Hamaguchi matches their outward calm with simple shots inside cars and long passages of the stage rehearsals. If the cinematography by Hidetoshi Shinomiya doesn’t call attention to itself, specific images stand out—such as Yusuke and Misaki preserving the sanctity of the car by holding their cigarettes out of the sunroof, or the stark appearance of the red car against snow in the final scenes. But all this outward control is enriched by how it deepens the characters when their carefully constructed façade cracks. For example, when Yusuke must play Uncle Vanya on stage, he’s overcome by the role and its relation to his life. As he tells an actor, “The text is questioning you. If you listen and respond, it will speak to you.” The same realization occurs during those long car rides, though in a different way—both Yusuke and Misaki have nothing to do but think about their late wife and mother, respectively.

But as a line from Murakami’s short story, which Hamaguchi and Oe carry over to the film, says, “If we hope to truly see another person, we have to start by looking within ourselves.” If Uncle Vanya’s characters find themselves reflecting on their unfulfilled and dissatisfying lives until a miserable conclusion, Drive My Car offers a note of optimism by allowing Yusuke and Misaki to find some way of addressing their failures, forgiving themselves for their perceived crimes, and moving forward. Though they don’t talk much at first, their hours together speak volumes, giving way to clarity. Hamaguchi’s film hinges on how two people connect; Yusuke and Misaki prompt each other to look inward and better accept the place others have in their lives. It’s an introspective film that emphasizes the importance of the road ahead instead of going around in the same circles every day, asking unanswerable questions of people who cannot respond.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review