Drive-Away Dolls

By Brian Eggert |

With brothers Joel and Ethan Coen exploring solo projects in recent years, it raises speculation about what each sibling brings to their collaborations in terms of narrative, philosophy, and aesthetics. Joel’s first directorial effort alone, the stark adaptation The Tragedy of Macbeth (2021), shot in black-and-white photography and using minimalist sets, deploys a lean but expressive approach to Shakespeare. Ethan Coen’s new film, Drive-Away Dolls, is a lesbian crime romp bursting with Almodóvarian color and bawdy humor. This follows his first documentary feature, 2022’s Jerry Lee Lewis: Trouble in Mind. From these examples, are we to assume that Joel is the serious brother and Ethan is the fun-loving brother? Is the former more responsible for Barton Fink (1991) and The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001), while the latter contributed more to Raising Arizona (1987) and The Big Lebowski (1998)? Doubtlessly, any such attribution is reductive and doesn’t consider the myriad complexities of each individual or the Coens’ distinct process, which is famously mysterious given their reluctance to talk to journalists about their partnership with any meaningful specificity.

Moreover, Drive-Away Dolls isn’t merely Ethan Coen’s first solo directorial effort of a narrative feature; it’s also his first film alongside Tricia Cooke, his wife and collaborator since 1990. Cooke, who identifies as a lesbian and admits her marriage to Coen is not what one would call conventional, wrote the screenplay, then called Drive-Away Dykes, in the early 2000s. Together, they pitched the idea to Allison Anders (Grace of My Heart, 1996). However, the production never materialized under Anders, probably because the cultural acceptance of LGBTQ+ characters in cinema wasn’t what it is today. Downtime during the COVID-19 pandemic gave Coen and Cooke the chance to work on the script together, and the result is a zippy, entertaining lark, but not much more. The lowbrow jokes and bloody violence align with the 1990s backdrop, where this sort of thing may have thrived. Today, it’s a negligible but diverting 84-minute throwback whose transgressive edge may have been more outrageous twenty years ago.

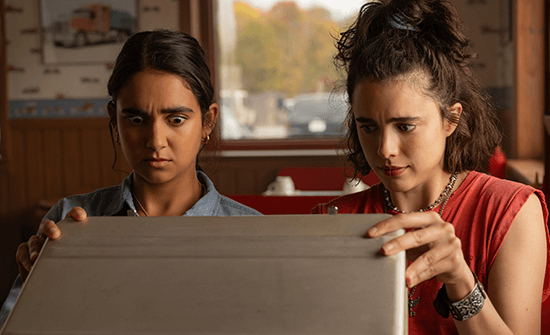

After a grim and cartoonish prologue, the movie introduces Jamie (Margaret Qualley), a Texas-born lesbian whose bad breakup with her cop partner Sukie (Beanie Feldstein) prompts her to leave town. Jamie convinces her friend Marian (Geraldine Viswanathan) to take a road trip from Philadelphia to Tallahassee. Jamie, unabashedly horny and sex-positive, also wants to get Marian, stuffy and reserved, laid—it’s been years. But after renting a car from a small drive-away service, their road trip, meant to be an adventure with stops at lesbian bars and BBQ joints along the way, becomes dangerous. It turns out, the car they rented has some mysterious cargo hidden in the trunk. Chief (Colman Domingo), a well-composed criminal type, orders his two goons to track down Jamie and Marian. Awkwardness and conflict also arise between the two queer friends, whose platonic relationship is tested. And while most of the movie’s conflicts would have been solved today by technology, the story unfolds in 1999, with Y2K and a presidential election looming.

Aside from her small role in last year’s Poor Things, Qualley has never given such a purely comic performance. She shines here, thanks partly to Coen and Cooke’s amusing dialogue and the emphatic twang she gives Jamie. The performance can be a bit stagey and mannerist at times, but it fits within the movie’s heightened world. Viswanathan fares better. Excellent in the TBS series Miracle Workers, she brings a deadpan humanity and vulnerability to Marian. Whereas Jamie always seems game for whatever the situation tosses her way, Marian constantly looks for reasons to self-sabotage her happiness—which predictably becomes a sticking point in their friendship. Cooke and Coen also seem more interested in Marian’s internal headspace, flashing back several times to her childhood, when she first started to recognize her attraction to the female form, bouncing on a trampoline or peering through a fence to spy on her sunbathing neighbor—a detail right out of the Coens’ A Serious Man (2009).

Aside from her small role in last year’s Poor Things, Qualley has never given such a purely comic performance. She shines here, thanks partly to Coen and Cooke’s amusing dialogue and the emphatic twang she gives Jamie. The performance can be a bit stagey and mannerist at times, but it fits within the movie’s heightened world. Viswanathan fares better. Excellent in the TBS series Miracle Workers, she brings a deadpan humanity and vulnerability to Marian. Whereas Jamie always seems game for whatever the situation tosses her way, Marian constantly looks for reasons to self-sabotage her happiness—which predictably becomes a sticking point in their friendship. Cooke and Coen also seem more interested in Marian’s internal headspace, flashing back several times to her childhood, when she first started to recognize her attraction to the female form, bouncing on a trampoline or peering through a fence to spy on her sunbathing neighbor—a detail right out of the Coens’ A Serious Man (2009).

Indeed, at times, Drive-Away Dolls feels like a compendium of visual and thematic nods to the Coen brothers’ work together. The first shots in a neon-laden bar recall similar ones in Blood Simple (1984). The two goons, the chatty one (Joey Slotnick) and the severe one (C. J. Wilson), serve as counterparts to the hired goons in Fargo (1996), played by Steve Buscemi and Peter Stormare. In one sequence, Jamie and Marian scream in prolonged unison, like John Goodman and William Forsythe realizing they left the baby on the hood of their car in Raising Arizona. Curlie (Bill Camp), the car rental owner, echoes so many stubborn functionaries from the Coens’ body of work, yet his end is almost tragic (“Won’t anybody save Curlie?”). The curious, infrequent theremin passage on Carter Burwell’s score harkens back to the UFO scenes in The Man Who Wasn’t There. But rather than simply redeploying artistic preoccupations used many times before, the movie feels like an effort to compile familiar tropes for the audience’s benefit (the executive in Barton Fink who wants “that Barton Fink feeling” comes to mind).

Other areas feel relatively unique. For instance, Ari Wegner’s textured cinematography gives way to flourishes in Cooke’s editing, such as frames that flip, fall, and rotate in a style reminiscent of pulpy ‘90s comedies or similar touches in Zombieland (2009). Then again, Drive-Away Dolls also has a throwback quality. Take the psychedelic transitions, which register like the acid flashbacks experienced by Jeffrey Lebowski, aka The Dude. These out-of-nowhere sequences star Miley Cyrus and, for some reason, were made to look like they’re a trippy Windows 95 screensaver shot on 16mm, though their origin only (sort of) becomes apparent in the last third of the film. A briefcase in the trunk of Jamie and Marian’s rental contains something mysterious—not the nightmarish revelation from 1955’s Kiss Me Deadly, a clear reference point here, but custom-made dildos. The joke is funny at first, but then eventually, it’s worn down to a nub. Still, the gag allows for a few hilarious asides, including the line, “Those penises are trouble!” That would be Drive-Away Dolls’ tagline on the poster in a better world.

Despite a few surprises, Drive-Away Dolls is a mostly predictable affair, best enjoyed by savoring not the destination but the journey, which feels long even though it’s under 90 minutes. The result suggests a John Waters movie in the post-Tarantino world, where the sheer raunchiness colors the familiar criminal goings-on. And while it’s tempting to compare the movie to Coen’s other work, given that Ethan Coen is working with another collaborator here, it’s perhaps more rewarding to consider what Cooke brings to the film. This includes an unabashed queer lens with sex and dildo jokes on the brain—a refreshingly loose alternative to the ultra-serious lesbian period pieces in recent years: Ammonite (2020), Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019), The World to Come (2021), Benedetta (2021), Blue Jean (2023), et al. The lively performances and few inspired moments mostly distract from the familiar quality of everything onscreen, but there’s not much beneath Drive-Away Dolls to make it memorable.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review