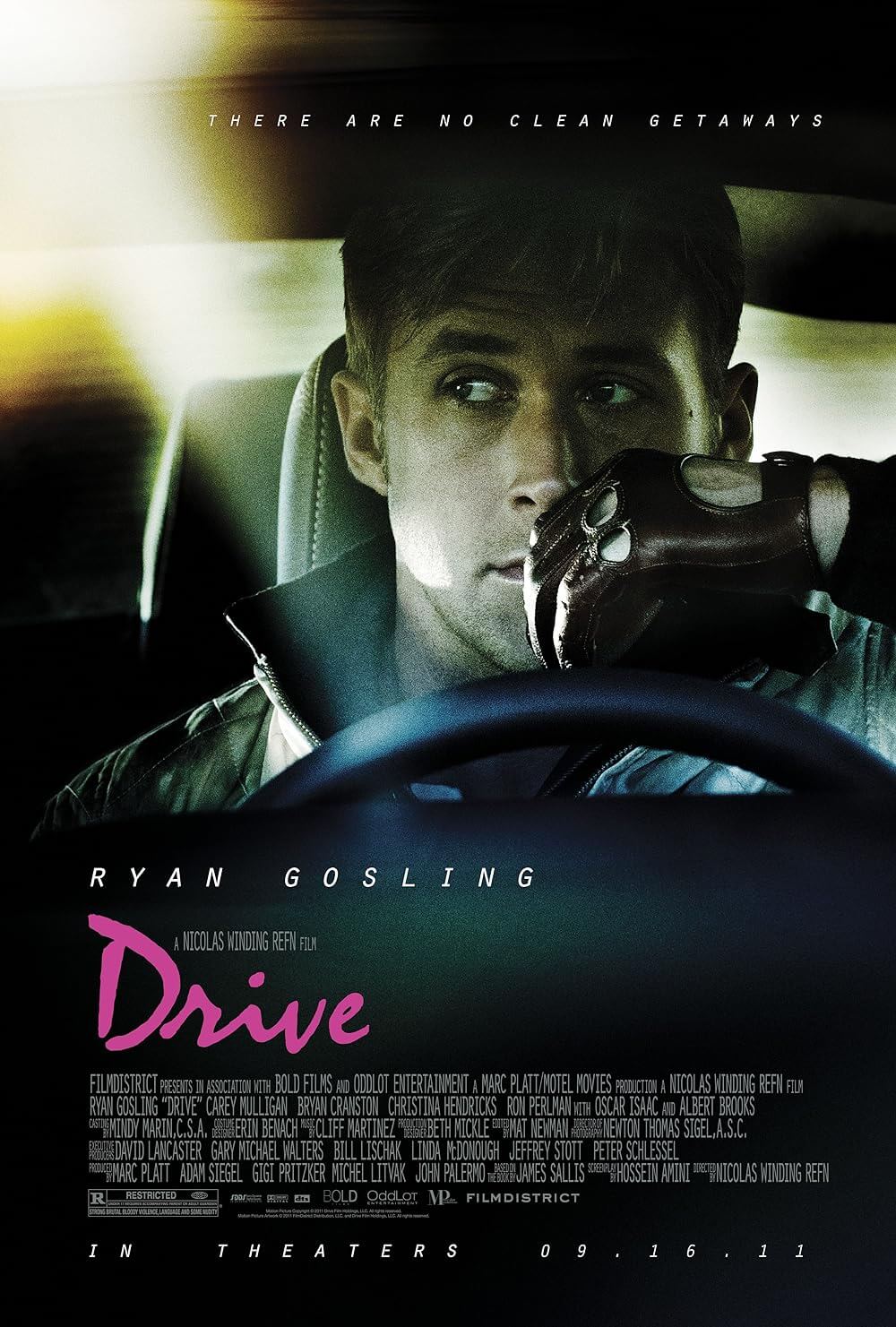

Drive

By Brian Eggert |

Much like a painter, filmmakers can achieve mastery with just a few broad strokes. Take any elegantly conceived shot or sequence from Drive and you have a rigorous work of art in itself, carefully considered in every detail. Combine them, and you find a graceful, bloody, existential, spare film where actions speak louder than words. How appropriate for an art film being billed as an action movie. Danish filmmaker Nicolas Winding Refn brings his manic and brooding styles from Bronson and Valhalla Rising to a work whose elements—car chases, mobsters, armed robberies, loads of stolen cash, and messy getaways—are familiar to the movies. But the treatment with which he handles the material is what makes it great, augmenting those conventions through a pace and severity that force us to consider every moment, and thus feel unprepared for what will happen next.

The man has no name, although he is credited as “Driver.” A poker-faced Ryan Gosling plays him as an inscrutable type with no history. His employer, the talky and reliably hard-luck mechanic Shannon (Bryan Cranston), describes how they met by saying he just appeared at his shop one day and asked for a job. What more is there to know? The Driver fixes cars and does some occasional stuntwork as a Hollywood wheelman, and other times he provides getaway services for criminals. In his recurring sales pitch, he explains the rules: “If I drive for you, you give me a time and a place. I give you a five-minute window. Anything happens in that five minutes, and I’m yours no matter what. I don’t sit in while you’re running it down; I don’t carry a gun… I drive.” The film opens with a thrilling prologue where we see this policy put to work, as with complete composure, he helps two crooks escape a swarming police net in downtown Los Angeles.

Perhaps Driver is an adrenaline junky, like so many of his kind in the action genre. At one point, standing in an elevator, he seems to doze off from a lack of movement. He drifts from place to place, seemingly detached, until he’s engaged behind the wheel, where he’s not obviously elated or jubilant but clearly activated. But if this is true, how does that explain his austere mannerisms even while driving? The key is watching Gosling’s muted facial expressions, dwelling on his few words, and waiting as the story unfolds. He becomes friendly with his neighbor, Irene (Carey Mulligan), a sweet innocent with a young boy, Benicio (Kaden Leos). He watches cartoons with Benicio and they talk about sharks. Is that shark the bad guy?, asks the Driver. Yes, says Benicio. How do you know?, the Driver asks, almost worried about how the boy will respond. Because he’s a shark, the boy says. Aren’t there any good sharks?, he asks. No. And so now we must consider that the Driver is a shark, his identity stripped by choice, his layers of teeth hidden behind a subdued exterior.

After a few days of bliss with Irene, her husband, Standard (Oscar Isaac), is released from prison and is almost immediately threatened by his former associates. Standard must rob a pawn shop to repay old debts; otherwise, Irene and Benicio will be in danger. The Driver offers his services to help but things go bad; the robbery is a setup, and Standard dies. But the crooks after Standard are now after Irene and her son, as well as the Driver. Somehow, this relates to two mid-level mobsters, the classier Bernie (Albert Brooks, terrific) and the rough-around-the-edges Nino (Ron Perlman). As the action plays out, startling violence erupts, elevated in its potency by gorgeous slow-motion and incredibly graphic bursts of carnage. The shark’s lips peel back to display its teeth, all bloody and clogged with gore, only to fall back and return to the quiet, kind-hearted hero who so delicately watches over Irene and Benicio.

Gosling’s performance is immaculate, nuanced, and controlled. Almost never cracking a smile except around Irene and her boy, his taciturn hero adopts the weight of Alain Delon’s role from Le Samouraї, where his cool is defined more by what he doesn’t say and the basic motivations behind his actions. Watch his hands. They almost always remain in his pockets; when they’re exposed, they flex in moments of poised anger and, building incredible tension, shake in with unbelievable intensity when the rage has overcome him. It’s the kind of singular, understated portrayal that’s overlooked by Oscar voters but remembered for a long time to come. Meanwhile, Brooks—that hilarious, self-loathing, sadsack genius behind comedies like Defending Your Life and Lost in America—should and likely will be remembered come awards season. He’s so deliciously villainous in his role and embodies the bad guy you love to hate, with all the same traits from his comedies, no less.

Advertised car chases and shootouts may attract action junkies, but the film’s arthouse mentality may confound them by bringing creative, meditative power to today’s characteristically choppy, unintelligible action output. Based on the book by James Sallis and adapted by Hossein Amini, the story better aligns with a French neo-noir—a patient, Jean-Pierre Melville-esque character study with flourishes of action. But it’s more about atmosphere than adrenaline. It’s also layered with electronic music by Cliff Martinez and ’80s-esque pop songs that oddly transform everything (despite recalling Tangerine Dream) into a dark, retro fairy tale about a mysterious hero. Drive earned Winding Refn the Best Director prize at this year’s Cannes Film Festival over powerhouse artists like Terrence Malick, Pedro Almodóvar, Lars von Trier, and Lynne Ramsay. The choice becomes clear as the director, hand-chosen by Gosling when producer Marc Platt gave him his pick of filmmakers, ingrains substance into every moment, along with cinematographer Newton Thomas Sigel’s handsome lensing. It’s a unique and demanding blend of familiar components put together in a way that revitalizes its sources, creating a reinvigorated, stylized realization of a movie you’ve seen before, but never like this.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review