Dragged Across Concrete

By Brian Eggert |

As I approach this review of S. Craig Zahler’s third film, Dragged Across Concrete, I am reminded of Roger Ebert’s review of The Hucksucker Proxy written in 1994. Ebert was split between his admiration for Joel and Ethan Coen’s style and what he perceived as the film’s lack of substance. He portrayed this division by writing out his internal debate in the form of two figures sitting on his shoulders, an angel arguing for the film’s merits, a devil arguing against them. Something similar occurs inside of me as I sit down to write this review, although I will resist representing my inner conflict the way Ebert did. A part of me enjoys the craft and immersive style that Zahler uses to tell his story, but another part sees the film as an ugly and irresponsible statement of racism, misogyny, limited roles for women, and narrow-minded politics. Throughout its two-hour-and-forty-minute runtime, I found myself alternating between feelings of disgust over how one might perceive these situations and feeling enrapt by the forceful way Zahler tells his story.

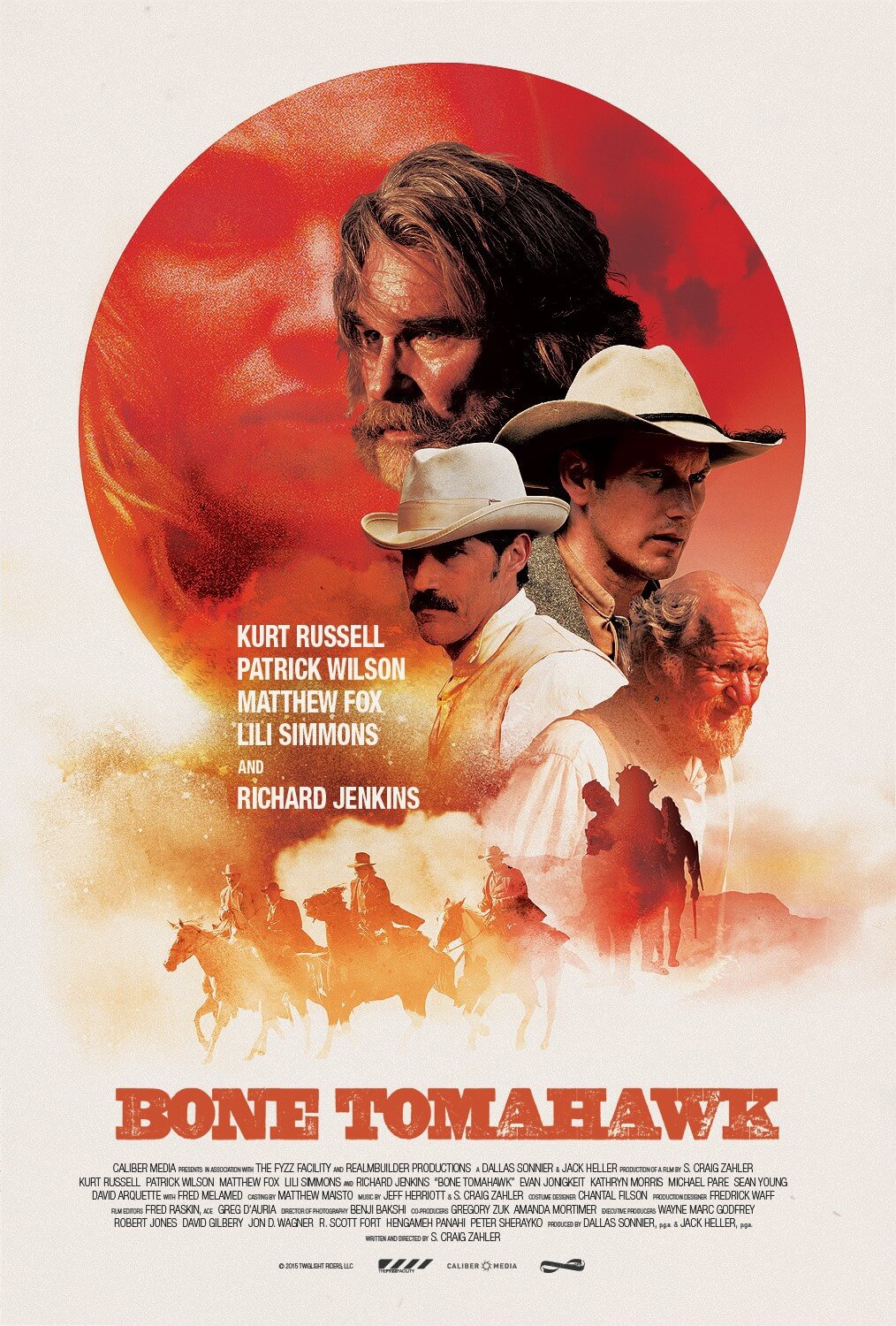

Curiously enough, Zahler’s last film, Brawl on Cell Block 99 (2017), featured a character whose face was literally dragged across concrete, tearing the flesh down to the skull. Zahler is known for grisly depictions of violence and characters who exhibit abrasive masculinity. But where his second film, along with his outstanding cannibal Western debut Bone Tomahawk (2015), softened their potent strains of machismo with protagonists who were at times vulnerable and empathetic in their motivations, his latest puts forth two despicable, racist, brutalizing cops played by two of Hollywood’s most outspoken right-wing voices. Given Zahler’s own political associations, it’s not unreasonable to question whether the writer-director sympathizes with the perspectives of these characters. Why else would this former novelist be drawn to tell a story about such characters? Then again, it would be a mistake to suggest that every author or director only tells stories about characters with whom they identify or agree with on every level. Storytellers should not be seen as reflections of their characters.

Just as Bone Tomahawk was a twist on classical Westerns and Brawl on Cell Block 99 was a riff on prison exploitation flicks of the grindhouse era, Dragged Across Concrete embraces hard-boiled cop movies of the 1970s. The two cops at the center are Brett Ridgeman (Mel Gibson), a nearly 60-year-old detective whose vile behavior has prevented him from moving up in the department, and his partner Anthony Lurasetti (Vince Vaughn), a capable cop who respects Ridgeman. When we first meet them, they use excessive force to capture a Latin American suspect and humiliate the perp’s topless girlfriend; the first act is caught on video, leading to their suspension. When their commanding officer (Don Johnson) informs them of the decision, they let their intolerance for political correctness be known in a clumsily written diatribe. They’re tired of the hypocritical media acting like moral watchdogs and preventing good cops from doing good police work. Lurasetti tries to make light of the situation. “I’m not racist,” he says, “Every Martin Luther King Day I have a cup of dark roast.” It’s difficult to watch this conversation without questioning whether Zahler endorses these views or simply puts them forth as character flaws.

Then again, moviegoers have tolerated racist cops before, from Dirty Harry Callahan to Popeye Doyle, and so one could argue that in his homage to 1970s policiers, Zahler has incorporated every aspect of those films, including the racist tendencies of these iconic detectives. Or perhaps Zahler aims to underscore the cultural feeling that police departments throughout the United States are inherently racist institutions. Or maybe Zahler agrees with everything Ridgeman and Laurasetti have to say about their disgust for the modern world, including their grumbles about smartphones and non-heteronormative gender roles. Note how Ridgeman’s wife, played by Laurie Holden, is a former cop and was “liberal as a former cop can be,” but after being stricken with MS and forced to live in a bad neighborhood, she finds herself becoming racist. The Ridgemans also worry for their teenage daughter who has been harassed by a group of African American teen boys, and they suspect that before long she will become a rape victim. Somehow, Lurasetti’s racism isn’t an issue for his African American would-be fiancée (Tattiawna Jones).

Then again, moviegoers have tolerated racist cops before, from Dirty Harry Callahan to Popeye Doyle, and so one could argue that in his homage to 1970s policiers, Zahler has incorporated every aspect of those films, including the racist tendencies of these iconic detectives. Or perhaps Zahler aims to underscore the cultural feeling that police departments throughout the United States are inherently racist institutions. Or maybe Zahler agrees with everything Ridgeman and Laurasetti have to say about their disgust for the modern world, including their grumbles about smartphones and non-heteronormative gender roles. Note how Ridgeman’s wife, played by Laurie Holden, is a former cop and was “liberal as a former cop can be,” but after being stricken with MS and forced to live in a bad neighborhood, she finds herself becoming racist. The Ridgemans also worry for their teenage daughter who has been harassed by a group of African American teen boys, and they suspect that before long she will become a rape victim. Somehow, Lurasetti’s racism isn’t an issue for his African American would-be fiancée (Tattiawna Jones).

Elsewhere, Zahler introduces Henry Johns (Tory Kittles), a black ex-con who must resort to crime to support his drug-addicted mother and wheelchair-bound little brother. Henry is one of the only sympathetic characters in Dragged Across Concrete, but he doesn’t have enough screentime to consider him the protagonist, even if the bookend scenes are about this character. Coming from his background as a novelist, Zahler doesn’t tell straightforward movie-style yarns; he’s entrenched in a given scene like an author is during the chapter of a book. He tells long, slow-burning stories that unfold in leisurely scenes, and they’re less about the forward momentum of a standard film than the layering quality of a novel. So while Henry isn’t a film protagonist in a traditional sense, the character’s arc is essential in making Dragged Across Concrete about more than Bridgeman and Lurasetti would make it alone. The fact that the first and last scenes involve Henry goes a long way in making the film overall palatable.

If there’s a logline for the film, it’s that the two down-on-their-luck cops decide to steal from a group of sadistic robbers in order to solve their own money problems. But nothing about Dragged Across Concrete is so straightforward. The film meanders from scene to scene, allowing the actors to saturate in the moment. Zahler’s embrace of a novelistic treatment of story in an otherwise cinematic form results in slow scenes that cannot help but steep the viewer in the events onscreen. One sequence puts the audience through the wringer in terms of a sheer visceral response. Without disclosing what happens, a subplot involving a new mother played by Jennifer Carpenter becomes a horrific display that feels like a demonstration of screen cruelty at its most manipulative, and reactionaries could even interpret the sequence to mean that women belong at home with their babies. Elsewhere, Zahler allows his actors to chew the scenery during a stakeout in which Lurasetti chomps down on the last few bites of a sandwich, much to the annoyance of his partner, in a moment that seems pulled from an Elmore Leonard book, as much of the film does. Finally, the protracted showdown between the two cops and a security van full of professional killers is as thrilling as anything Zahler has put on the screen.

One could not be blamed for despising Dragged Across Concrete for its apparent politics, nor can one easily ignore that Mel Gibson of all people is playing a racist cop, nor should you. Zahler might claim that he’s just trying to tell a good story and has no ulterior motives in mind, but I have a sneaking suspicion that that’s not exactly true. There’s too much speechifying to ignore. It’s difficult to avoid seeing Ridgeman as Zahler’s mouthpiece when he declares, “I don’t politic, and I don’t change with the times, and it turns out that shit’s more important than good, honest work.” Even so, the film makes excellent use of its performers’ strengths. Gibson has demonstrated in recent years, with Edge of Darkness (2010) and Blood Father (2016) for instance, that he’s best as imperfect and unrelenting figures. Vaughn, too, at least under Zahler’s direction, has shown a wider range than we’ve ever seen before. But in spite of its strengths and undeniable capacity to invest the viewer in the proceedings, I remain uneasy about the ideas contained within the film and unsure of what they’re trying to achieve. Although I have an admiration for how the film accomplishes its enveloping atmosphere, and my reaction to the film is more positive than negative, I take lasting apprehension as a sign that not all is well with Dragged Across Concrete.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review