Doubt

By Brian Eggert |

Doubt advances in a seemingly straightforward manner to ask questions of an irresolute nature. Examining opposing approaches in the search for faith, truth, and ultimately basic certainty, the film doesn’t make a vast statement on the issue, though some might argue otherwise. John Patrick Shanley adapted his Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-winning play into an expert film, with a precision and lucidity in its intellectual quandary that few motion pictures can muster, making the experience at once entertaining and full of substance.

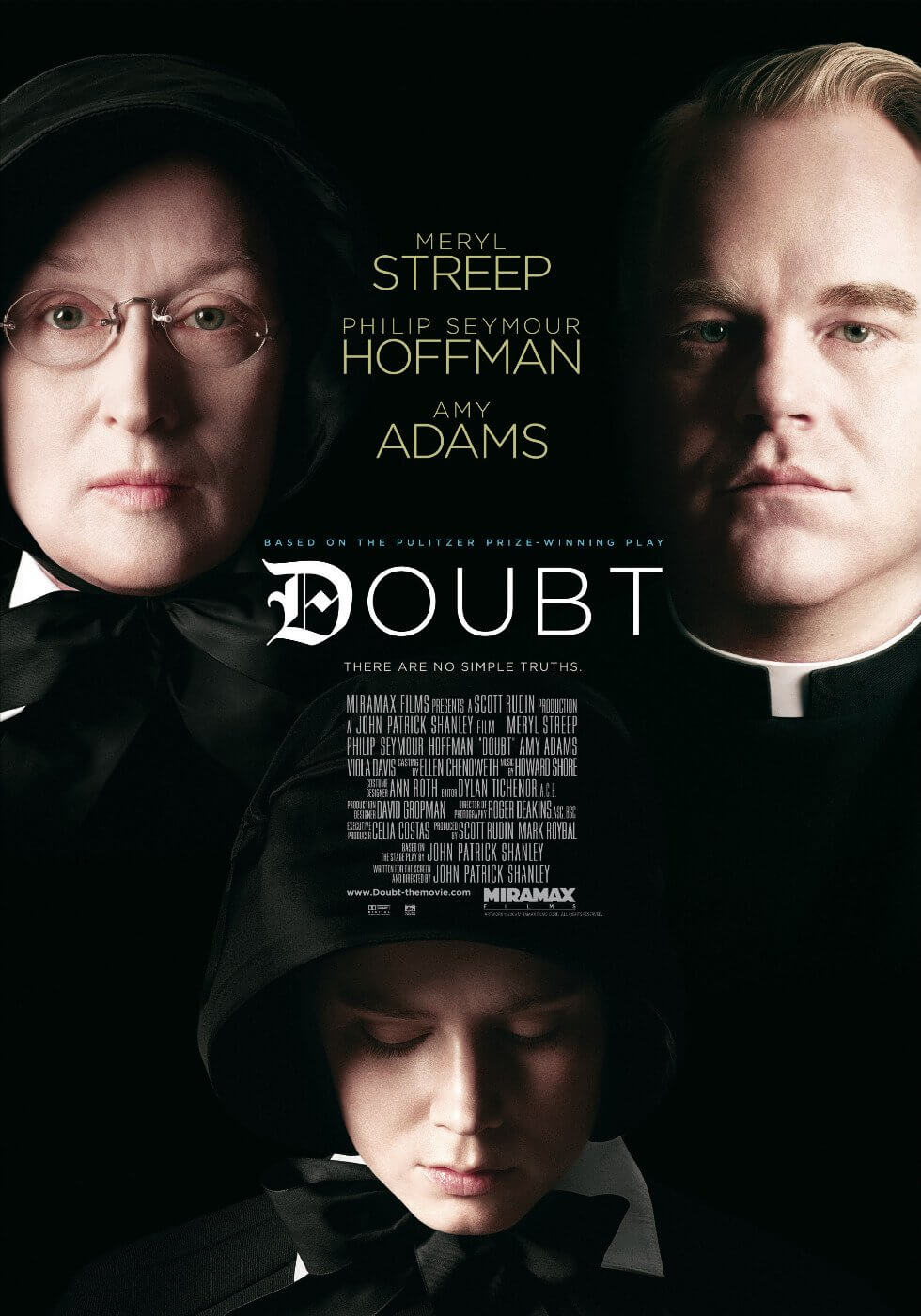

The setting is autumn of 1964, in The Saint Nicholas Church School in the Bronx. In an era where nuns still wielded rulers like battle axes, slapping the wrists of those they felt deserved it, Sister Aloysius (Meryl Streep), the Catholic school’s principal, prefers a swift hand delivered to the back of the head. She sees misconduct everywhere and immediately corrects it. Father Flynn (Philip Seymour Hoffman) presides over the institution, hoping to progressively bring the church into a community-friendly modern age. He dares to suggest they sing secular songs, like “Frosty the Snowman,” in the upcoming Christmas pageant, much to Sister Aloysius’ disgust.

There’s no questioning that the Sister and Father have opposing views. And so, their reactions to what comes next are no surprise. Innocent and perhaps naïve, Sister James (Amy Adams) reports to Sister Aloysius that Father Flynn called student Donald Miller (Joseph Foster) away from class, and when the boy returned, he had alcohol on his breath. Sister Aloysius assumes, or rather knows, the worst must have happened, that Father Flynn engaged young Mr. Miller in some inappropriate manner. Father Flynn denies the accusation, believing Sister Aloysius’ blind certainty a symptom of her narrow rule.

What follows is a Cold War of religious idealism versus reform, of old versus new. Sister Aloysius represents established dogmatism not to be questioned, structured on a solid foundation that supports its sturdy architecture, complete with evident cracks in the façade like an ancient cathedral. Father Flynn exists as the flexible and restorative filler, willing to adapt himself to support the traditional with a new air of modernism. The warfare takes place during Flynn’s wonderful sermons, behind office doors, through arguments and inner debates, with position and logic wielded like nuclear weapons. Shanley doesn’t waste time on the needless details of what Father Flynn may have done. Of course, it may be of a sexual nature. Then again, there may be some emotional identification taking place, and that’s all. The audience is left to determine this for themselves. The film makes no admissions, though viewers might disagree on that point as well. What we’re left with is two very opposing sides vying to justify their stations.

Streep and Hoffman are two powerhouse performers, leading us through this exhausting cat-and-mouse game. Both embody their roles and become their characters, disappearing into the masterfully formed details ranging from mannerisms to inflections in their voices. We’ve seen both Streep and Hoffman give great performances before, and their ability to vanish into their roles allows audiences to fully appreciate their idealistic combat. The collateral damage in this holy war is Adams’ Sister James and Viola Davis, playing Donald’s mother. Adams portrays yet another childlike adult, but she excels in this, and her placement in this story is key. Davis, however, steals the show in her sole scene with Streep, not only revealing a major crux to the ongoing plot, but offering the most sobering of outside viewpoints.

Consider the title Doubt in all its simplicity, and you’ll find the basic meaning of this film. Doubt, which Father Flynn talks about in his sermon in the film’s first scene, leads to questions and exploration. Certainty lacks a tolerant viewpoint, whereas uncertainties allow for open-minded consideration. Perhaps Father Flynn hopes doubt will, in due course, lead to answers in the form of God. And while Sister Aloysius resents the idea of uncertainty in her unbending world, her certainty, which has slowly mutated into righteousness, needs doubt to sustain itself. Ironically, when the answers people seek in their lives remain elusive, doubt is filled in with religion or some other construct.

Retaining integrity and clarity of purpose in every perfectly timed line of dialogue, every perfectly placed shot by cinematographer Roger Deakins (No Country for Old Men), and every perfectly suggestive piece of commentary, Doubt is a small masterpiece. The film questions certainty, as the title very plainly suggests, but more than that, it acknowledges through allegory the inherent illusion of conviction, faith, or any form of assuredness ranging from religion to science. And yet, the philosophical ponderings of the film never detach from the emotional context. So while it asks audiences to think, the film’s drama doesn’t subside into intellectual preaching and remains centered on the brilliant, deceptively simple story.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review