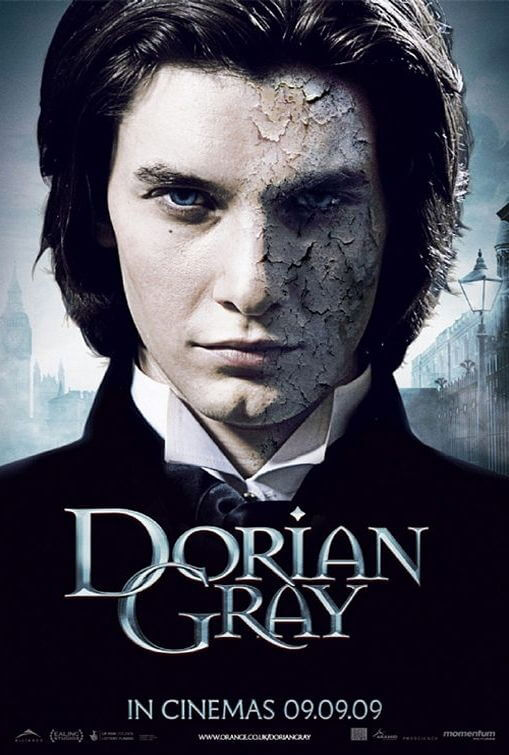

Dorian Gray

By Brian Eggert |

The most disturbing aspect of Oscar Wilde’s singular work of nineteenth-century horror literature, The Picture of Dorian Gray, is that its best rendition into cinema is, by default, Oliver Parker’s 2009 adaptation. Aside from an electronic score that emerges here and there, Dorian Gray is a gothic Victorian tale, a full costume period piece that thankfully wasn’t reconfigured into a contemporary setting. For this, we must be thankful. But despite its dedication to the era, Parker’s film over-emphasizes the story, from the title character’s behavior behind bedroom doors to the gory effects used to create his decaying portrait.

In 1945, director Albert Lewin created a dark vision that starred Hurd Hatfield and boasted Oscar-nominated makeup, though the outcome plays rather flatly today. Malcolm McDowell appeared in Dorian, a regrettable modernization from 2001. And Stuart Townsend made the role villainous in 2003’s absurd literary mashup The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. With the exception of Lewin’s film for the quality of its production, these are all forgettable adaptations. And Parker’s film might be forgettable too if it weren’t for one or two strong performances and some sleek-looking photography by Terry Gilliam’s frequent cinematographer Roger Pratt (Brazil, 12 Monkeys).

Orphaned as a child and adopted by a wealthy man who beat him, Dorian Gray (Ben Barnes) arrives among London’s elite to receive his vast inheritance. The first order of business is a portrait by enamored artist Basil Hallward (Ben Chaplin), who completes a prized work believed to have perfectly captured the much-discussed beauty of the young Dorian. Quickly the naïve innocent is corrupted by Lord Henry Wotton (Colin Firth), whose motto “There’s no shame in pleasure” becomes Dorian’s too, after Wotton convinces him that youth is everything. While admiring his portrait, Dorian whispers to himself that he would give his soul for eternal youth, and the devilish deal is made with no one the wiser, not even Dorian. Only after cutting his hand and seeing later that his painting, not his flesh, was affected, does Dorian realize he can never be harmed and will never age.

Orphaned as a child and adopted by a wealthy man who beat him, Dorian Gray (Ben Barnes) arrives among London’s elite to receive his vast inheritance. The first order of business is a portrait by enamored artist Basil Hallward (Ben Chaplin), who completes a prized work believed to have perfectly captured the much-discussed beauty of the young Dorian. Quickly the naïve innocent is corrupted by Lord Henry Wotton (Colin Firth), whose motto “There’s no shame in pleasure” becomes Dorian’s too, after Wotton convinces him that youth is everything. While admiring his portrait, Dorian whispers to himself that he would give his soul for eternal youth, and the devilish deal is made with no one the wiser, not even Dorian. Only after cutting his hand and seeing later that his painting, not his flesh, was affected, does Dorian realize he can never be harmed and will never age.

Versed in Wilde’s work, Parker has given us likable versions of An Ideal Husband and The Importance of Being Earnest (though Anthony Asquith’s version could never be outdone). But another filmmaker might have chosen a better solution than to make Dorian’s long life no more than a series of sexual encounters. In his search for pleasure and new experiences, Dorian passes from conquest to conquest in graphic R-rated detail, engaging countless women (and the occasional man, which seems an underexplored theme in the film, given the homoerotic symbolism of Wilde’s book). However, Wilde only alluded to Dorian’s activities, writing “What Dorian Gray’s sins are no one knows.” Parker removes that mystery by answering the question with lots of sex and drugs, which in turn removes Barnes from the responsibility of having to portray inner demons, resulting in his one-dimensional performance.

Meanwhile, Dorian’s eternal soul grows more debauched and rotten as the film progresses, as shown with a maggoty painting enhanced (a term used sardonically) by computer effects and groaning sounds. As Wilde’s novella was in many ways a condemnation of the conceit of decorative portraiture displayed in one’s own home, Parker’s distracting use of CGI to transform the portrait into a reactive, pulsating organism feels out of place. The film could have earned some subtlety points had the filmmakers simply used paintings that appear more and more grotesque, and then saved their fancy special effects for the moment when Dorian finally becomes as ugly as his picture.

There are performances to savor, such as the wonderfully devilish Colin Firth playing Dorian’s depraved mentor. As time goes on and the character grows older, Firth’s Wotton begins to regret his behavior and the actor shows more depth in his performance than Barnes does in the whole film. In a role written for the movie, Rebecca Hall (Vicky Cristina Barcelona) appears in the third act as Wotton’s daughter, Emily, and with her open-minded allure brings about Dorian’s questions of conscience. Hall has yet to break out and become a star, but she’s charming and talented enough that with any luck it won’t be long. Chaplin is also very good as the enamored painter.

Taking liberties with Wilde’s source, Parker’s adaptation accentuates far too much, insisting on special effects and even some contrived suspense in place of the author’s dark drama. But horror movies today rarely offer a supernatural scenario without tossing in some blood splattering, plenty of breasts, and lousy CGI. Dorian Gray is certainly no exception. Though, audiences seeking Wilde’s grim tale in movie form have few other choices, as another adaptation isn’t bound to emerge for some time now. This might be one of the rare occasions where moviegoers have to break down and—gulp—read the book.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review