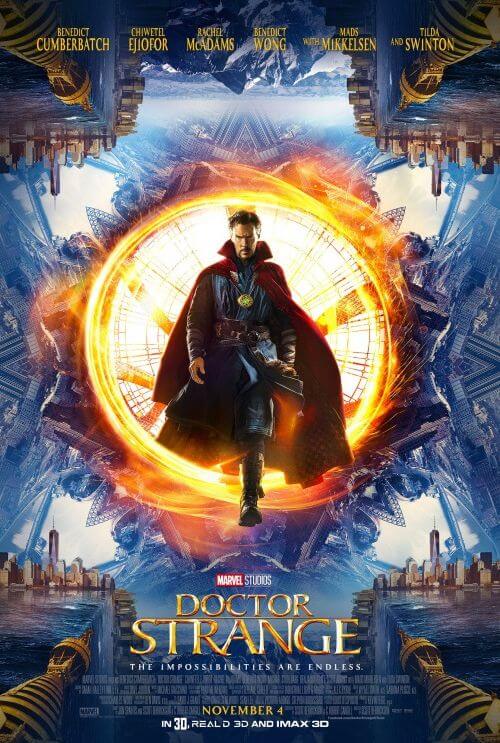

Doctor Strange

By Brian Eggert |

Doctor Strange takes the ever-expanding Marvel Cinematic Universe in a bold new direction, at least it appears that way. Exploding onto the screen with some dazzling CGI and another impressive MCU ensemble, the film delves into a Harry Potter-esque world of mysticism and magic. It was directed by Scott Derrickson, whose career in subpar horror like Sinister, Sinister 2, and Deliver Us from Evil does not bode well for the production; not that the particular filmmaker matters much when it comes to the Marvel Studios assembly line. To be sure, Disney and Marvel have overseen Doctor Strange, ensuring the script by Derrickson and C. Robert Cargill meets their requirements and delivers an accessible, family-friendly product consistent with the greater MCU. The unique presence of theosophy in this entry aside, the material does not stray from the same basic MCU narrative structure accompanying their fourteen releases thus far. And that’s just fine.

The Marvel Comics character debuted in the hippy-dippy sixties and inhabits a realm (multiple realms, actually) steeped in spells and black magic. Originally, Doctor Strange appealed to psychedelic users and college students open to an amalgamation of Eastern philosophies and mythology on the comic’s page. But the character’s circulation has been intermittent since his 1963 debut, appearing in various Marvel books over the years, including a position on the Avengers and Illuminati, though never for very long. He even appeared in a forgotten 1978 television movie and a beleaguered 1992 film (renamed Doctor Mordrid due to some untimely licensing issues). Adapting the Marvel character into a major motion picture contains the same daring it took to adapt Guardians of the Galaxy or Ant-Man, in that the subject matter remains fringe and outside of normal superhero fare; but then again, the risks on Marvel’s part are few.

Indeed, it’s tempting to draw comparisons between every film in the MCU. Doing so would certainly illustrate how each superhero has common traits, as well as how, as the mastermind of the MCU, Kevin Feige has homogenized the superhero narrative into a repeatable and hugely profitable formula. Structurally, most MCU pictures adhere to a predictable blueprint regardless of whether they occupy a unique subgenre, such as a Shakespearian drama in Thor or a spy-thriller with Captain America: The Winter Soldier. For film theorists, the MCU and the superhero genre, in general, have resulted in a decline of creativity and cinematic diversity in the industry. They also make lower- and middle-budgeted productions more difficult for filmmakers to get financed, as studios want the higher probability of a sure thing with an established intellectual property. Despite all this, the formula works, and MCU films are usually made entertainingly and with technical skill.

Doctor Strange is no exception. The story follows egomaniacal neurosurgeon Stephen Strange, played by Benedict Cumberbatch with all the pomposity of his beloved turn as Sherlock Holmes on the popular BBC series. After an accident renders his hands useless and Western medicine provides no solutions, he seeks answers in the Far East. He finds himself studying the astral plane, multiverse dimensions, and eternal powers under The Ancient One (Tilda Swinton), an age-old instructor of the magical arts. Alongside a straight-faced librarian named Wong (Benedict Wong) and idealist trainer Karl Mordo (Chiwetel Ejiofor), Strange quickly learns to see beyond his physical weakness and control untold energies, all the while remaining impossibly arrogant. Meanwhile, the audience takes slightly longer to look past The Ancient One’s whitewashed casting.

If you’re thinking this setup sounds suspiciously familiar to the original Iron Man, you would be right. Both Tony Stark and Stephen Strange embark on similar journeys that set aside their former careers, reach outside of their physical ailments, and subdue their unbridled egos. After they discover and explore their great powers in a fun second act, they finally use said powers in the action-packed finale to save the world. The similarities come complete with an underdeveloped, uninteresting villain, here named Kaecilius and played by Mads Mikkelson. For reasons not adequately explained, Kaecilius has a master plan of bringing Earth into the “dark dimension” of Dormammu, an omnipotent evil being. On the periphery, Rachel McAdams costars in a thankless role as Strange’s former lover and coworker Christine, appearing whenever the screenplay needs a familiar face. Likewise, Michael Stuhlbarg plays one of Strange’s fellow surgeons, and his big scene involves getting free chips from a vending machine.

If you’re thinking this setup sounds suspiciously familiar to the original Iron Man, you would be right. Both Tony Stark and Stephen Strange embark on similar journeys that set aside their former careers, reach outside of their physical ailments, and subdue their unbridled egos. After they discover and explore their great powers in a fun second act, they finally use said powers in the action-packed finale to save the world. The similarities come complete with an underdeveloped, uninteresting villain, here named Kaecilius and played by Mads Mikkelson. For reasons not adequately explained, Kaecilius has a master plan of bringing Earth into the “dark dimension” of Dormammu, an omnipotent evil being. On the periphery, Rachel McAdams costars in a thankless role as Strange’s former lover and coworker Christine, appearing whenever the screenplay needs a familiar face. Likewise, Michael Stuhlbarg plays one of Strange’s fellow surgeons, and his big scene involves getting free chips from a vending machine.

Strange himself proves less interesting than the film’s many worlds and dimensions that fold over on each other in visuals obviously inspired by Christopher Nolan’s Inception. The character’s dramatic arc does not contain grand emotions, nor does he change much over the film’s two-hour runtime, other than his eventual realization that he has a greater calling besides practicing medicine. It’s a basic conflict for a basic character, and the script’s kitschy humor and pop-culture references become clear distractions from the fact that Doctor Strange relies heavily on the audience’s fondness for Cumberbatch, which is significant. Fortunately, the fast-paced plot and dizzying action sequences keep the audience diverted for the duration.

Derrickson seems to relish moments where Doctor Strange takes on the look of a kaleidoscopic acid trip fueled by images from 2001: A Space Odyssey and tinged with luminescent black lighting. When The Ancient One sends Strange spinning across the universe on a nightmarish journey of multiplying baby hands and glowing spatial formations, our eyes practically pop out of our heads. Later, Strange brings Kaecilius and his goons into the Mirror Dimension, a cracked place where whole cities duplicate and float in space, as though M. C. Escher designed the sequence on LSD. To be sure, the film makes enjoyable use of its out-there visuals and the limitless possibilities of magic, particularly in the time-looped climax. It’s all set to Michael Giacchino’s score, which adopts some atmospheric and moody themes; but when the action reaches its pinnacle, viewers may notice the music shares more than a few notes with Giacchino’s Star Trek theme.

As one would expect, Doctor Strange looks good and provides diverting, popcorn-munching entertainment throughout. Most of the characters feel either just one or two-dimensional, while others seem downright unnecessary or like obligatory writerly devices (for example, McAdams shows up when the film needs to remind us of Strange’s humanity). The familiar quality of the story could be distracting for some, except the anything-is-possible world has enough character to make up for what personality the screenplay lacks. Fortunately, the actors fulfilling these roles elevate our involvement, while the continuation of the MCU ensures the characters will grow in future material, such as appearances in another character’s sequel (look for Doctor Strange in Thor: Ragnarok, coming in 2017). Though Doctor Strange may represent little more than the latest piece in an expansive series, it presents a familiar story in a hallucinatory and playful way.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review