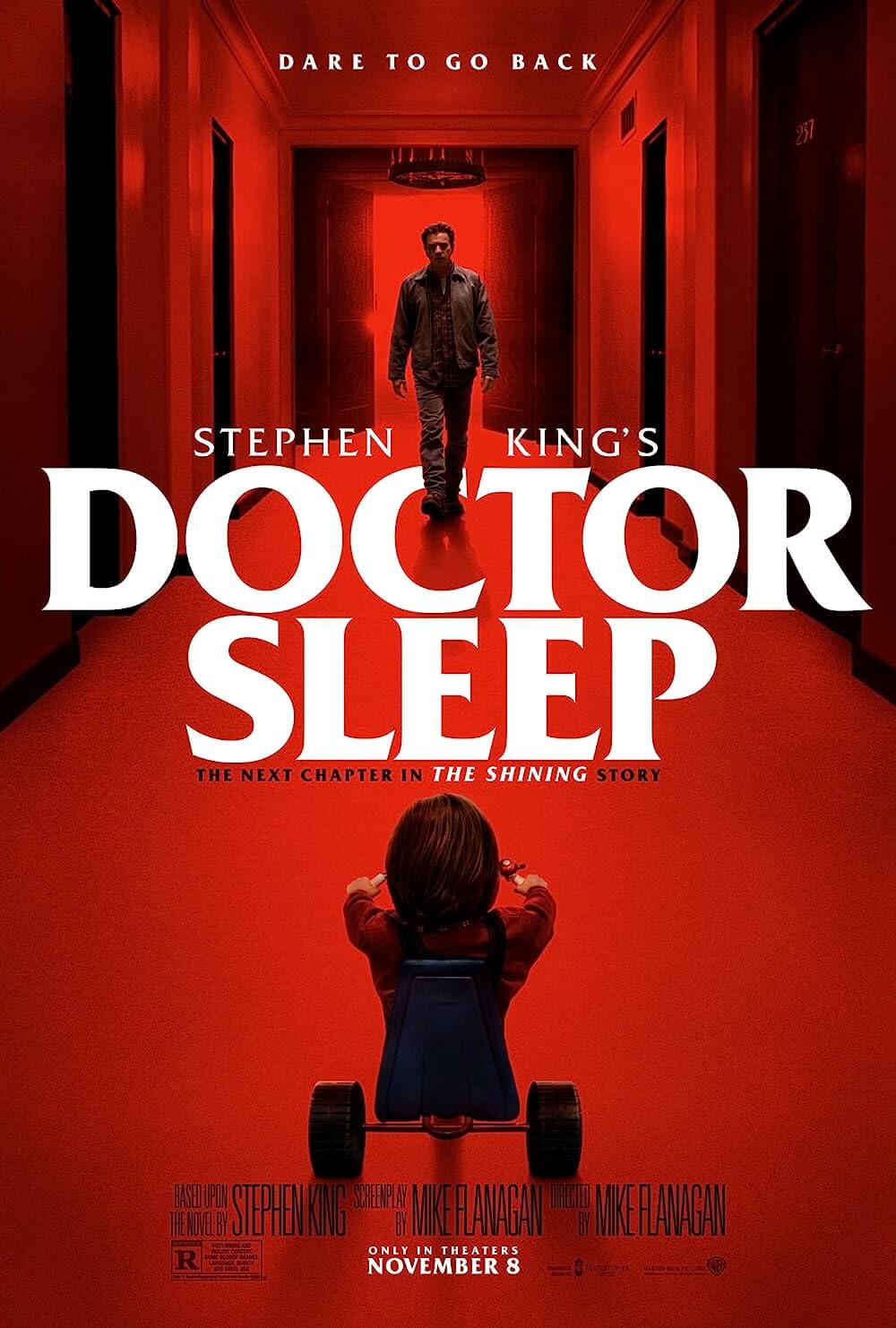

Doctor Sleep

By Brian Eggert |

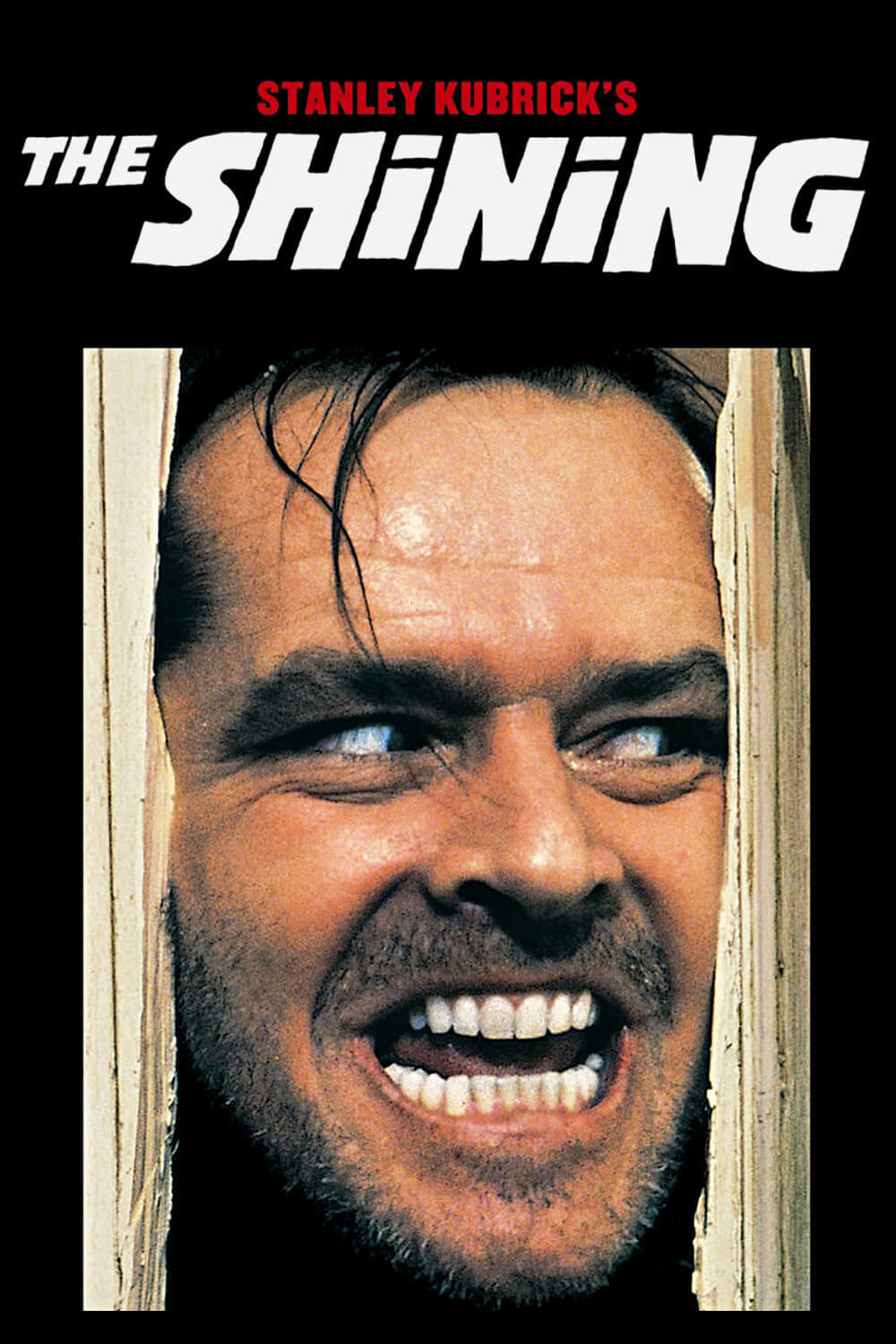

Though based on Stephen King’s novel from 1977, Stanley Kubrick’s film of The Shining has surpassed its source material in terms of cultural recognition. Kubrick’s 1980 masterpiece has been studied and obsessed over as few films have, inciting countless theories in books, documentaries, and video essays from scholars and fixated horror aficionados. The labyrinthine corridors of its plot have entrenched the film’s imagery, from the patterned carpeting of the Overlook Hotel to the distinct performances captured during the infamously long production, into cinematic iconography. It represents a hallowed ground for many, not to be tampered with or sullied, even though the film diverged from its source and created a fissure between the author and Kubrick’s take on the material. Making a sequel to The Shining nearly 40 years after its release seems destined for failure. But when King wrote a rather good follow-up in 2013, called Doctor Sleep, the material followed the events in his original novel and not Kubrick’s film. And so, how could an adaptation of the sequel reconcile the literary foundation of King’s two books yet acknowledge the visual authority established by Kubrick? Writer-director Mike Flanagan has an answer.

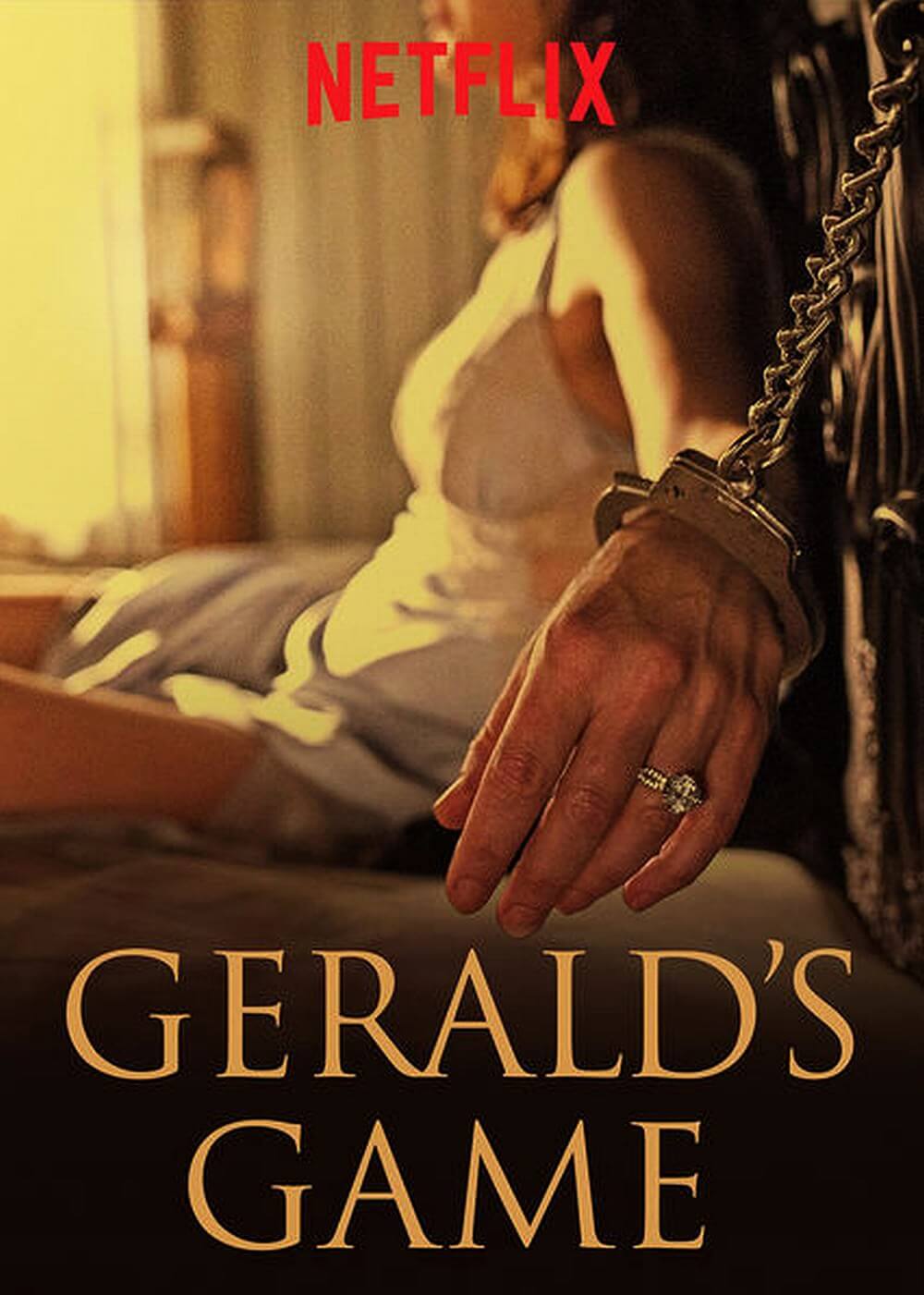

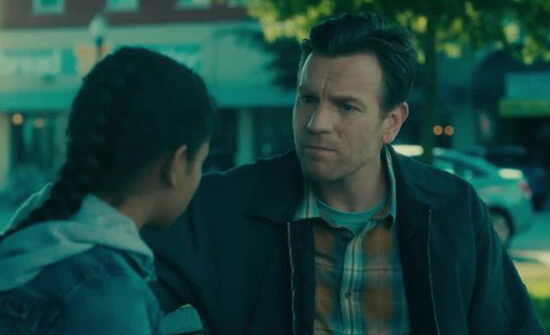

Flanagan’s Doctor Sleep is a generous adaptation at 151 minutes, and he adds his personal signature onto the works of two masters. Fortunately, his own output has established a set of thematic and visual preoccupations, which serve as a third layer to King’s book and Kubrick’s film. Watching the sequel, you hear the voices of both sources, and Flanagan’s voice joins them to achieve a kind of belated harmony. The filmmaker has made a name for himself with tales about people dealing with past trauma by representing their emotional specters as the supernatural. Such is the case with the underrated Ouija: Origin of Evil (2016) and his Netflix series The Haunting of Hill House (2018), as well as his 2017 take on King’s Gerald’s Game—works that value depth of character over cheap scares. Instead, the scares often enhance the dramatic concentration of his work. But if Flanagan excels at telling stories about his protagonists coming to terms with the wounds of their past, then the damage central to Doctor Sleep’s main character, Dan Torrence, played with afflicted sincerity by Ewan McGregor, originated during the events of The Shining. It seems as though King’s sequel has given Flanagan an ingenious way to revisit Kubrick’s film while driving the story forward, as great sequels must do.

One of the lingering questions about Kubrick’s version involves a mystery about what happens in the Overlook. Was it a haunted hotel that possessed Jack Torrence to attempt to kill his family with an ax? Or was Jack plagued by alcoholism or cabin fever, or both? The opening scenes of Doctor Sleep, a comparatively straightforward text next to the maze of Kubrick’s film, seek to clarify the events, while at the same time aligning with King’s book. The story opens in 1980 when the young Danny (Roger Dale Floyd) learns from the spirit of Dick Hallorann (Carl Lumbly) that the Overlook was “eating” young Danny’s “shine”—his ability to receive ghostly signals and communicate telepathically. It’s an idea that comes to horrifying life with the introduction of Rose the Hat, played by Rebecca Ferguson, a seductive and menacing figure who first appears when she uses flowers and an enchanting song to tempt, and ultimately devour, a young girl with a touch of the shine. Rose the Hat leads a vagabond group of quasi-vampires called the True Knot, who imbibe “steam,” the smokey essence of anyone who has the shining. Their motto: “Eat well. Stay young. Live long.” Indeed, the True Knot has survived on steam for centuries, inhaling the lifeforce of their victims to extend their own lives to near-immortality, and keeping the excess stored in small metallic canisters.

Decades later in 2011, Dan, bearded and ragged looking, has numbed his psychic abilities with alcohol, having drifted through life in a series of random hookups, blackout benders, and odd jobs. One morning after a drunken barroom brawl, he wakes up next to a strung-out woman he met the night before, and just as he begins to leave, he finds her small child. Quickly getting out of there, he’s pursued by the thought of these two, and the shameful realization that both surely died after he left. This overwhelming guilt leads him to a New Hampshire boarding house, where Danny finds a friend and sponsor in Billy Freeman (Cliff Curtis), who sets him up with a job and introduces him to Dr. John (Bruce Greenwood), the leader of the local AA group. Dr. John also secures Danny a position at the local hospice clinic, where he uses his shining abilities to ease dying patients into their eternal, restful slumber, earning him the nickname “Doctor Sleep.” But Dan’s demons remain, and he’s plagued by his alcoholism and the ghosts of the Overlook Hotel—the decrepit woman in the bath, the twin girls, et al.—the same things that corrupted his father. Fortunately, Hallorann taught Dan a neat trick as a child: he can lock away those ghosts inside mental boxes, psychic traps stored in his mind where they can’t hurt him.

On the periphery, Dan communicates telepathically with a teenage girl named Abra Stone (Kyliegh Curran, supremely confident), whose ability to shine extends beyond his own skills. For years, they have been aware of each other only as a psychic feeling, occasionally articulated by messages written on a chalkboard in Dan’s room. Exploring the limits of her powers one night, Abra watches from several states away as the True Knot kidnaps and consumes a young boy (Jacob Tremblay, from Room, who doesn’t escape his kidnappers this time). Abra, as in “abracadabra,” witnesses the extent of Rose the Hat’s cruelty as she heightens and purifies the boy’s steam by torturing him in an excruciating scene. But Abra’s presence does not go unnoticed by Rose, who immediately recognizes that she’s being watched by “big steam”—Abra, a white whale that could feed the True Knot for ages. What unfolds is a fascinating cat-and-mouse game between three parties: the predatory True Knot; Abra, who wants to expose them; and Dan, whom Abra enlists to help. Of course, amid the preponderance of psychic maneuvers and real-world murders, there are more earthbound matters to negotiate. How, for instance, does Abra explain to her parents (Jocelin Donahue, Zackary Momoh), willfully ignorant of their daughter’s talents, that she’s secretly, not to mention telepathically, friends with a middle-aged man?

Inevitably, the confrontations, which occur both on the astral plane and in a thrilling shootout sequence, lead to a showdown at the Overlook Hotel. Up to this point, Flanagan’s adaptation has been mostly faithful to King’s book, to the extent that the filmmaker has brought entire sequences to life as the reader envisioned them in their mind’s eye. The climactic sequence must reconcile with Kubrick’s film, however, as in the book, the Overlook was destroyed by neglected boilers, but at the end of Kubrick’s film, it was left standing. This is where some viewers will check out or have trouble with Doctor Sleep, cinematically speaking. It’s not as though Flanagan merely pays homage, as Steven Spielberg did in his dazzling ode to Kubrick’s film in Ready Player One (2017). Rather, Flanagan recreates the cinematic space, using the setting as a haunted house where the steam-eating hotel and the imprint of Dan’s father still linger. Doctor Sleep employs convincing reproductions, including uncanny performances by Henry Thomas and Alex Essoe as Jack and Wendy Torrence, which may betray the memory of Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall for some. But inserting clips from Kubrick’s film or animating Nicholson with CGI may have proved distracting and would have left the proceedings to feel fragmented, whereas Flanagan’s approach lends a sense of wholeness to his film, allowing it to emerge from under the shadow of Kubrick.

Of course, Kubrick’s fingerprints remain everywhere, perhaps because Warner Bros. could not avoid exploiting the intellectual property and lasting iconography, perhaps because Flanagan could not resist imbuing his sequel with the resonant power of The Shining. Regardless, the film never feels like a cheap homage; Flanagan always finds a narrative purpose for his links to Kubrick’s film. For instance, the Newton Brothers composed the score for Doctor Sleep, drawing from the tones and jarring strings of Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind’s original score. But underneath it, they also use the persistent heartbeat from The Shining, a pulse that in the sequel denotes the presence of psychic activity, adding a sense of dread beneath a few crucial scenes. Elsewhere, Flanagan embeds a few not-so hidden details as Easter eggs, such as the appearance of the adult Danny Lloyd in a brief scene or how Dr. John’s office looks like Ullman’s “impossible” interview room from The Shining. The effect may offend some purists, but Flanagan’s treatment mostly avoids winks or dramatically unnecessary callbacks. It never distracts from the events at hand, Dan’s psychological hangups, or the plan to stop Rose the Hat and her gang of steam-suckers.

Moreover, Flanagan does not merely create a copy of Kubrick’s visual style; he inhabits the spaces of The Shining while delineating his own visual approach with cinematographer Michael Fimognari, a frequent collaborator. Also serving as editor, Flanagan allows the material to breathe at a deliberate pace. Doctor Sleep carries on in immersive, almost novelistic fashion, allowing the characters to remain the focus as he builds an imperative mood. Note how Flanagan chooses to include a scene where, while unearthing one of the True Knot’s victims from a shallow grave, Billy remembers how he used to hunt. He recalls one time when he wounded a deer, which he proceeded to track for several days before finding its rotting body. That smell, he says, is the same smell of the rotting child they’re digging up—and it’s a description that cannot help but create a phantom stench in our olfactory senses. It also illustrates that Flanagan is more interested in the grim journey to dig up the corpse than the macabre sight itself. Doctor Sleep is filled with moments such as this, where the director uses a gradual build to enhance the impact of a scene. Next to the comparatively cold and emotionally remote treatment by Kubrick, Flanagan’s touch is warm, involving, and affecting.

In the end, the effectiveness of Doctor Sleep depends on the viewer’s willingness to accept Flanagan’s meddling in Kubrick’s territory. It will undoubtedly prove bothersome to the late master’s loyal following, and I admittedly wrestled with it at first. King fans will have less to complain about, aside from the final act’s detours away from the page. But for his part, Flanagan has constructed more than a shameless publicity-stunt-of-a-sequel; it’s a thoughtful and meaningful experience that justifies its existence with its deliberate pacing, dimensional characters, and confident filmmaking. Ferguson alone validates the film; it’s a compelling and monstrous role, iconic in its own right, and terrifically cast and acted alongside the excellent performances by McGregor, Curran, and Curtis. Ultimately, Doctor Sleep manages to do the impossible by somehow remaining faithful to both King’s books and Kubrick’s film, yet in a way that creates a unique amalgam of both sources, producing something altogether new. It’s an unlikely feat, while at the same time representing a testament to Flanagan’s unmistakable trademarks as a horror auteur.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review