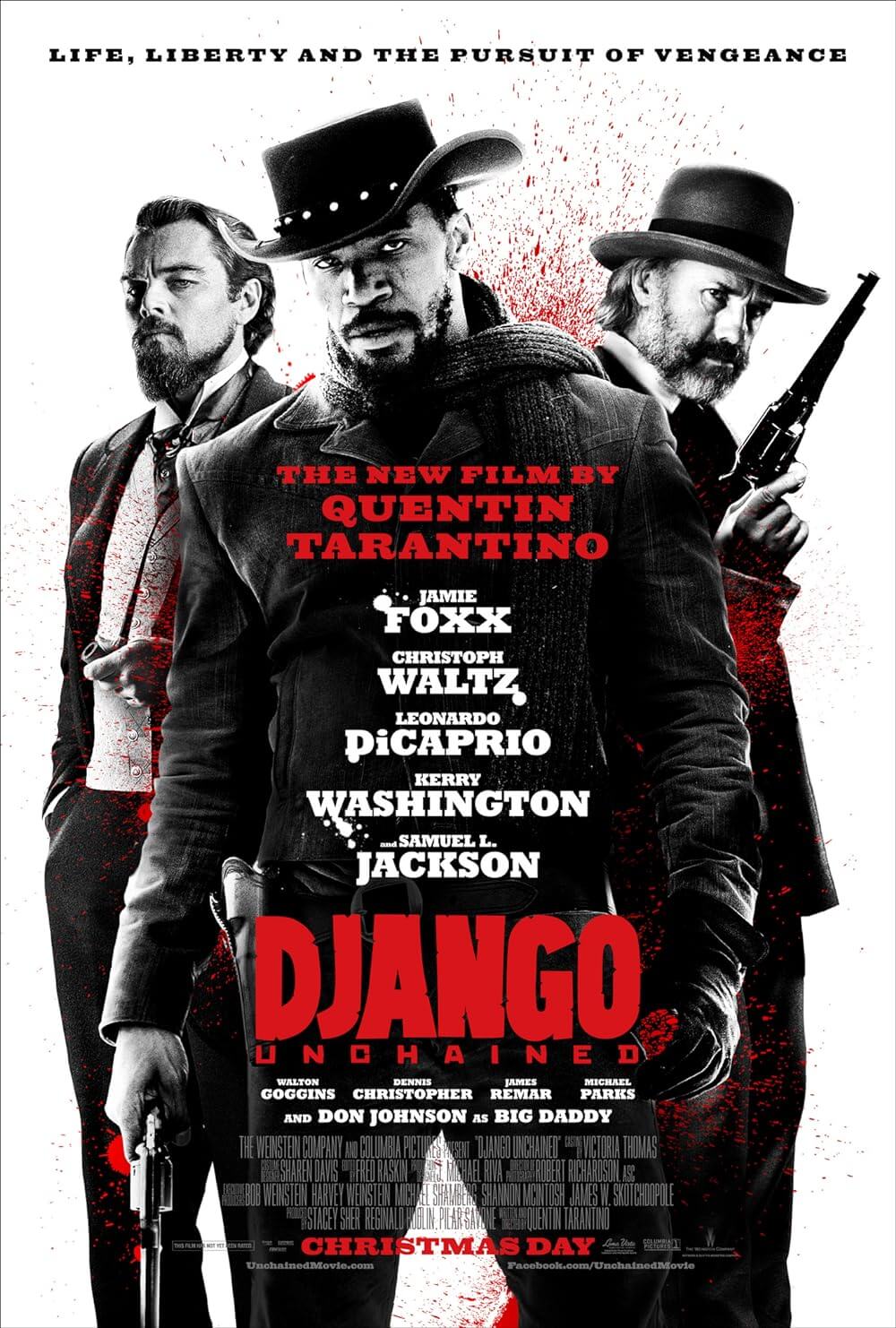

Django Unchained

By Brian Eggert |

Quentin Tarantino continues to play with history and cinematic tradition in Django Unchained, his self-proclaimed “Southern” whose deposits of blaxploitation and Spaghetti Western filmmaking engage a violent saga of revenge and historical atrocity. After Inglourious Basterds, in which he set loose a cadre of Jewish-American soldiers to rewrite history by killing Adolf Hitler, Tarantino’s eighth film arms a freed slave to seek vengeance on the Old South for centuries of racial degradation. Out of necessity to disguise what would otherwise be an unflinching reminder of America’s sordid past, Tarantino’s highly stylized and self-conscious approach embraces an almost cartoonish level of cinematic boldness: he uses quick camera zooms; historical embellishments and inventions galore; splatters blood about the screen as if tossed from buckets; and his loud soundtrack combines twangy Western songs, the post-modern presence of rap, and Ennio Morricone riffs—all in service of this ethically just, wildly entertaining, often controversial motion picture.

Reactions to the film have inspired nothing if not passionate assessments, with questions and accusations of racism and the trivialization of slavery at the center of these arguments. Spike Lee condemned the picture as “disrespectful” for its hundred-plus uses of the “N-word” and the depiction of slavery in an almost satirized light, while the NAACP Image Awards nominated it for Outstanding Motion Picture. Tarantino’s pastiche remains both political and therapeutic, using graphic acts of violence against the black slave characters in his film as examination, and doles out arguably even more violent retribution against his deplorable slave-owning characters. Instead of treating his tragic subject matter with pure gravity, Tarantino, ever the pop-culture revisionist, chooses cinematic fantasy to produce catharsis and allow, for one of the rare times in a motion picture Western, someone other than a white man the opportunity for bloody justice. Aside from a few such examples like Navajo Joe (1966), an admitted influence for Tarantino on Django Unchained, traditionally wronged white men have the exclusive moral right in Westerns to exact vengeance, the archetypal example being The Searchers (1956), where John Wayne kills countless Comanches in pursuit of his kidnapped niece.

By shifting the action from the Wild West to the Old South, Tarantino’s longstanding attraction to black culture receives its first complete embrace, although his third film Jackie Brown (1998) comes very close to this as well. The director’s racial role reversal begins on a chill night “somewhere in Texas” in 1858, when the wordy-but-eloquent German bounty hunter Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) stops a chain gang of slaves being escorted by two white traders. Schultz is looking for a slave named Django (Jamie Foxx) to identify the Brittle Brothers, whom Schultz has never seen. Dispensing with Django’s white escorts and freeing him from his shackles, the rather moralized Schultz, the sole sympathetic white man in the picture, offers Django a proposition of $25 a Brittle head should he assist. As for Django’s slave status, Schultz casually remarks, “For the time being, I’m going to make this slavery rigamarole work to my advantage.” Schultz may seem like an amoral, cold-blooded bounty hunter, but his cultured humanity finds slavery disgusting and uncivilized, if not completely silly.

By shifting the action from the Wild West to the Old South, Tarantino’s longstanding attraction to black culture receives its first complete embrace, although his third film Jackie Brown (1998) comes very close to this as well. The director’s racial role reversal begins on a chill night “somewhere in Texas” in 1858, when the wordy-but-eloquent German bounty hunter Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) stops a chain gang of slaves being escorted by two white traders. Schultz is looking for a slave named Django (Jamie Foxx) to identify the Brittle Brothers, whom Schultz has never seen. Dispensing with Django’s white escorts and freeing him from his shackles, the rather moralized Schultz, the sole sympathetic white man in the picture, offers Django a proposition of $25 a Brittle head should he assist. As for Django’s slave status, Schultz casually remarks, “For the time being, I’m going to make this slavery rigamarole work to my advantage.” Schultz may seem like an amoral, cold-blooded bounty hunter, but his cultured humanity finds slavery disgusting and uncivilized, if not completely silly.

Schultz imparts his man-hunting skills onto the quick study Django and finds his new sidekick has a backstory that draws comparisons to the German legend of Siegfried and Brunhilda on the mountain. Inspired, Schultz agrees to help rescue Django’s wife, named Broomhilda (Kerry Washington) no less, who was sold by their former owner to sadistic slaver Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio) after the couple tried to escape captivity together. After a winter’s worth of learning the bounty trade, Django and Schultz make their way to Candyland, Candie’s notorious Mississippi plantation, where the two put on an act as businessmen interested in purchasing a “mandingo” fighter—the suave-yet-base Candie’s chief pastime involves holding to-the-death gladiatorial bouts between slaves. One such scene of hand-to-hand combat ends with a hammer and is so jarring you have to look away. The victor is rewarded with a single beer. When our heroes eventually reach Candyland, Candie’s aged top house slave, Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson), distrusts the new guests, especially Django, who puts on airs as a freed black man riding a horse. In a way, Candie’s raw evil and sadism are less aggravating than the diabolical nature of Stephen’s Uncle Tom, whose loyalty to his master never questions white superiority.

In comparison to Pulp Fiction, Death Proof, or Inglourious Basterds, Tarantino’s narrative structure proves linear and less reliant on protracted scenes of dialogue that lead to bursts of violence—although there’s no shortage of bloodshed here. Granted, two or three passages play out in Tarantino’s usual lovingly prolonged fashion, such as the dinner table discussion at Candyland that becomes unbearably tense as Candie delivers his phrenological thesis on the innate submissiveness in black slaves, or a comical discussion on the lack of visibility from within the hoods worn by Ku Klux Klan members. Django Unchained is a journey that seems to reach its destination at the flamboyantly named plantation but then takes some unexpected turns in the last act. The climax does not arrive at the film’s bloodiest shootout, but it carries into threatening territory. Throughout the picture, Tarantino spills as much blood as his two Kill Bill volumes combined, if not more. Every time a bullet makes contact, flowing splashes of red burst, as though everyone onscreen was made of balloons that pop when penetrated. As always, the director’s instances of violence feel less realistic than intentionally over-the-top, including several threats to and punishments on male genitalia.

To say the violence becomes excessive is missing the point, which has more to do with Tarantino’s embrace of Spaghetti Westerns and his abhorrence of slavery than with purveying mindless killing. More than the obvious genre practitioner Sergio Leone, whose The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) lends Django Unchained its epic feel and runtime (2 hours and 45 minutes), Tarantino develops from Sergio Corbucci. As always, a level of Tarantino’s work is “about” cinema itself, paying homage through a series of references and reverences that comes across less as derivations but rather as pure inspiration. Behind Corbucci’s aforementioned Navajo Joe and his cult-classic Django (1966), which starred Franco Nero (who appears here in a cameo), Corbucci’s gritty, actionized style finds a modern counterpart in Tarantino’s hands. Other nods: Richard Fleischer’s Mandingo (1975), the slave fighting yarn from which Tarantino borrowed the name for his film’s bloodsport; Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) with Schultz’s retractable gun-up-his-sleeve; and virtually any Western between 1930-1970 that used a title song and featured two men riding out against a common evil (i.e., a lot of them).

To say the violence becomes excessive is missing the point, which has more to do with Tarantino’s embrace of Spaghetti Westerns and his abhorrence of slavery than with purveying mindless killing. More than the obvious genre practitioner Sergio Leone, whose The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) lends Django Unchained its epic feel and runtime (2 hours and 45 minutes), Tarantino develops from Sergio Corbucci. As always, a level of Tarantino’s work is “about” cinema itself, paying homage through a series of references and reverences that comes across less as derivations but rather as pure inspiration. Behind Corbucci’s aforementioned Navajo Joe and his cult-classic Django (1966), which starred Franco Nero (who appears here in a cameo), Corbucci’s gritty, actionized style finds a modern counterpart in Tarantino’s hands. Other nods: Richard Fleischer’s Mandingo (1975), the slave fighting yarn from which Tarantino borrowed the name for his film’s bloodsport; Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) with Schultz’s retractable gun-up-his-sleeve; and virtually any Western between 1930-1970 that used a title song and featured two men riding out against a common evil (i.e., a lot of them).

That Tarantino happens to be a post-modern trendsetter in cinematic style and also a renowned actor’s director at the same time is still a curiosity. Writing Schultz specifically for Christoph Waltz, who won an Oscar for his supporting role in Inglourious Basterds, Tarantino uses the actor’s strength for long bouts of verbal showmanship. Schultz is a complicated character with a probing sense of morality that takes him into unforeseen nobility. We cannot help but want to know more about him, whereas Foxx’s Django remains a singular epitome of human revenge. Foxx is perfectly suited for Django, a role originally meant for Will Smith; he has a level of vulnerability that makes scenes where he must “stay in character” around Candie unbearable for the audience. And then there’s DiCaprio’s villain, a vile and superficial specimen with a yellow-toothed grin. A brilliant moment occurs when Schultz reveals that Candie’s revered author Alexandre Dumas was black, and we see the vain weakness exposed. DiCaprio may finally earn himself an Oscar for this lurid portrayal, a performance where the actor is clearly having fun being what must be one of the most despised characters in movie history. As suggested, however, even worse is Jackson’s Stephen, who puts on quite a show in front of guests, but behind closed doors becomes his master’s strategic confidant. Meanwhile, Tarantino’s supporting cast includes some of the director’s favorites from yesterday and today: Zoe Bell, Robert Carradine, Bruce Dern, Jonah Hill, Don Johnson, Michael Parks, M.C. Gainey, and Tom Wopat.

Only Quentin Tarantino could so effortlessly walk the line between offensive and entertaining, and then smash that line as he does in Django Unchained. His strangely hilarious, shockingly brutal, artistically inspired, and always mesmerizing style provides a level of intertextual cinema that challenges as much as it provides a rollicking good time. Take away the vengeful blood and guts and torturous violence, and Tarantino has provided a moralist film with a resounding repulsion toward slavery that occupies his film’s characters and themes. America refuses to look into its past and acknowledge the atrocity of slavery in full scope; Tarantino isn’t afraid to do this in such a way that refuses to look away. He may adhere to history’s excessive use of a certain word and portray the Old South as unflinchingly unpleasant, but if Tarantino ever gets to a point where he’s pulling his punches to satisfy his detractors, there would be far more to complain about. Shot with a magnificent eye by cinematographer Robert Richardson, Django Unchained is an instant classic within both Tarantino’s oeuvre and the Western genre, and the way it toys and transcends racial and historical sensitivities makes it perhaps the most divisive motion picture of 2012.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review