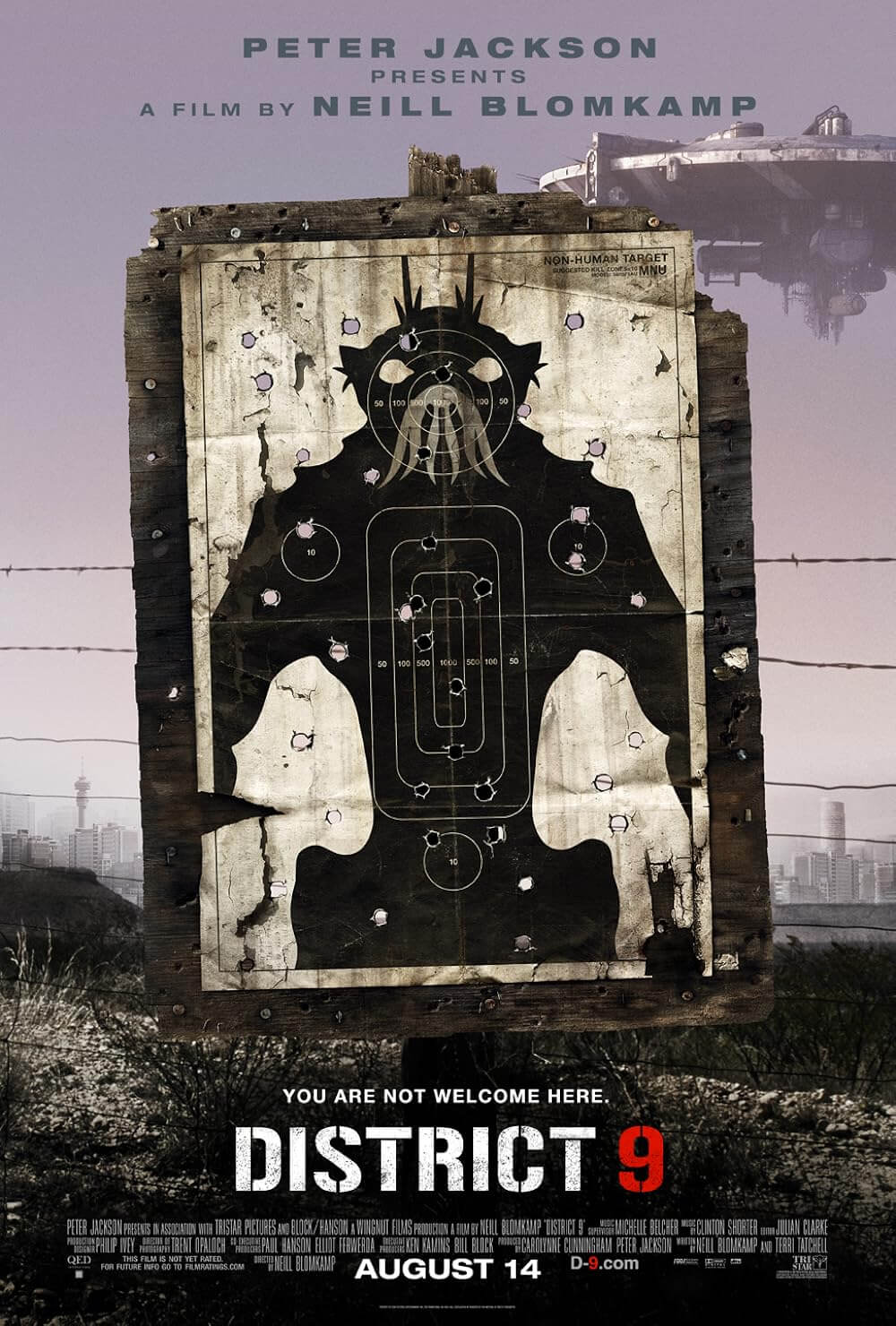

District 9

By Brian Eggert |

When aliens first arrive on planet Earth, they’re not here to conduct anal probes or wipe out our species in some elaborate terra-forming effort. They’re not lizards hiding under human masks, nor are they cutesy gray children with large black eyes and oversized heads. After they arrive, they’re found quivering and starving from their long journey in their malfunctioning spaceship, which hovers over Johannesburg. Their technology has broken down; their food and fuel are all but gone. They look frightening, something between a crustacean and a cockroach; accordingly, locals call them “Prawns.” After twenty years, their ship remains frozen above the South African city, where they live in a third-world zone fenced off from humans and monitored by a world force assigned to supervise them. Hated by the neighboring population, they’re persecuted and attacked for being aliens, taking the term xenophobia to a new, literal extreme.

This is the setup of District 9, one of the best science fiction motion pictures you’ll see this year, possibly ever. Produced by Peter Jackson and directed by newcomer Neill Blomkamp, it’s made with bravado production value through Jackson’s company Wingnut Films, constructed to look as though the footage was thrown together, though it’s assembled with impressive computer effects and clever editing. Like a CNN special report, mock security cameras and documentary footage capture what sad horrors unfold in the plot, most of them as a result of violent prejudice. The outcome provides weighty relativity to political and sociological calamities currently plaguing our world, and most importantly, it all feels painfully real. What makes it great science fiction is that it presents a metaphor for every occupation, every encampment, and every forced relocation in human history.

Segregated into their slums filled with run-down shanties and refuse, the alien survivors, described as drones accustomed to following precise orders but now lost in disarray, have become comfortable in poverty. They cannot leave their ghetto, so they rummage through garbage, sniffing for cans of cat food, for which they’ve developed a strange craving. Local Nigerian warlords use this hunger to incite trade for alien weapons, which can only be operated by a user with alien DNA. Enter Multi-National United (MNU), the company that seeks to move the “Prawns” from their rusty tenements to new, improved, government-issue tents far away from Johannesburg. Meanwhile, MNU conducts top-secret experiments on the aliens, because that’s what governments do, trying to discover a way for humans to exploit the alien weaponry.

Wikus van de Merwe (Sharlto Copley) heads the field operation to relocate some two million aliens from their shacks to their concentration camp-style tents, having gotten the promotion thanks to his powerful father-in-law. He and the soldiers following him patrol through District 9 to get the aliens’ “scrawl” on eviction notices; they search homes for prohibited activity and set illegal egg sacks on fire, chuckling about the mass abortion they’ve caused. They stumble upon one alien, dubbed “Christopher Johnson,” who seems more intelligent than most. Van de Merwe becomes personally involved when he exposes a secret device Johnson has been slowly assembling over several years.

Wikus van de Merwe (Sharlto Copley) heads the field operation to relocate some two million aliens from their shacks to their concentration camp-style tents, having gotten the promotion thanks to his powerful father-in-law. He and the soldiers following him patrol through District 9 to get the aliens’ “scrawl” on eviction notices; they search homes for prohibited activity and set illegal egg sacks on fire, chuckling about the mass abortion they’ve caused. They stumble upon one alien, dubbed “Christopher Johnson,” who seems more intelligent than most. Van de Merwe becomes personally involved when he exposes a secret device Johnson has been slowly assembling over several years.

Though the CGI aliens are impressively sympathetic, Copely carries the film. He seems innocent and good-hearted in early interviews, but then we see him reacting to the “Prawns” in the slums, his small-mindedness exposed. In the second and third acts, however, his character transforms so that the audience is curiously drawn to him, perhaps because he begins to empathize with the aliens more in a unique way. Copely doesn’t lose us through this progression. He’s an unknown actor with only one credit to his name, but he gives an affecting performance that helps propel the film beyond some kitschy alien yarn into the realm of potent allegory.

Based on a real incident during the South African apartheid—the Cape Town relocation of the 1960s, where black Bantu residents of “District Six” were forced out after their government declared the area fitting only for the white-skinned South Africans of Dutch descent—the film’s writers Blomkamp and Terri Tatchell make a startling parallel. Bantu victims of this apartheid speak in throaty clicks, just as the aliens in the film do. Even the Dutch name van der Merwe furthers the analogy, positioning our hero on the enemy’s side until he eventually, and dramatically, sees the perspective of those he’s persecuting. Here we see how science fiction is used in its most optimal way, to echo our society, or in this case human history, and reflect the sheer horror of the actual events through an entertaining disguise.

And how entertaining Jackson and Blomkamp have made this film, so ripe with ideas and nonstop momentum. Alien weaponry eventually comes into play and incites some nasty, shockingly gory moments of human explosion, and the finale contains better robot action than any toy-based blockbuster might offer. But it’s a film that keeps the audience thinking without becoming preachy. Aliens are blown away at first like meaningless insects, furthering the idea that racism is blind and unsympathetic; no doubt, Dutch Afrikaners saw Bantu as inhuman, allowing them to wave off their disposal just as easily. It’s that detachment that we see displayed here, which is slowly replaced by empathy for the aliens and an utter rejection of human intolerance.

Blomkamp doesn’t miss a step. His film is cynical, funny, smart, exciting, and satirical—all without losing his audience’s involvement in the scenario. This being his first feature-length film, the director has demonstrated enough ingenuity and craft so that Hollywood will certainly claim him for future projects (we should be so lucky). With District 9, he’s helped make science fiction relevant again. And along with Moon and Star Trek, 2009 is slowly becoming an unparalleled year for the genre. Through an involved and complex parable, the picture’s brainy filmmaking dazzles with originality and imagination, and what’s more, remains as pure entertainment that will incite further discussion and admiration as time goes on.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review