Disconnect

By Brian Eggert |

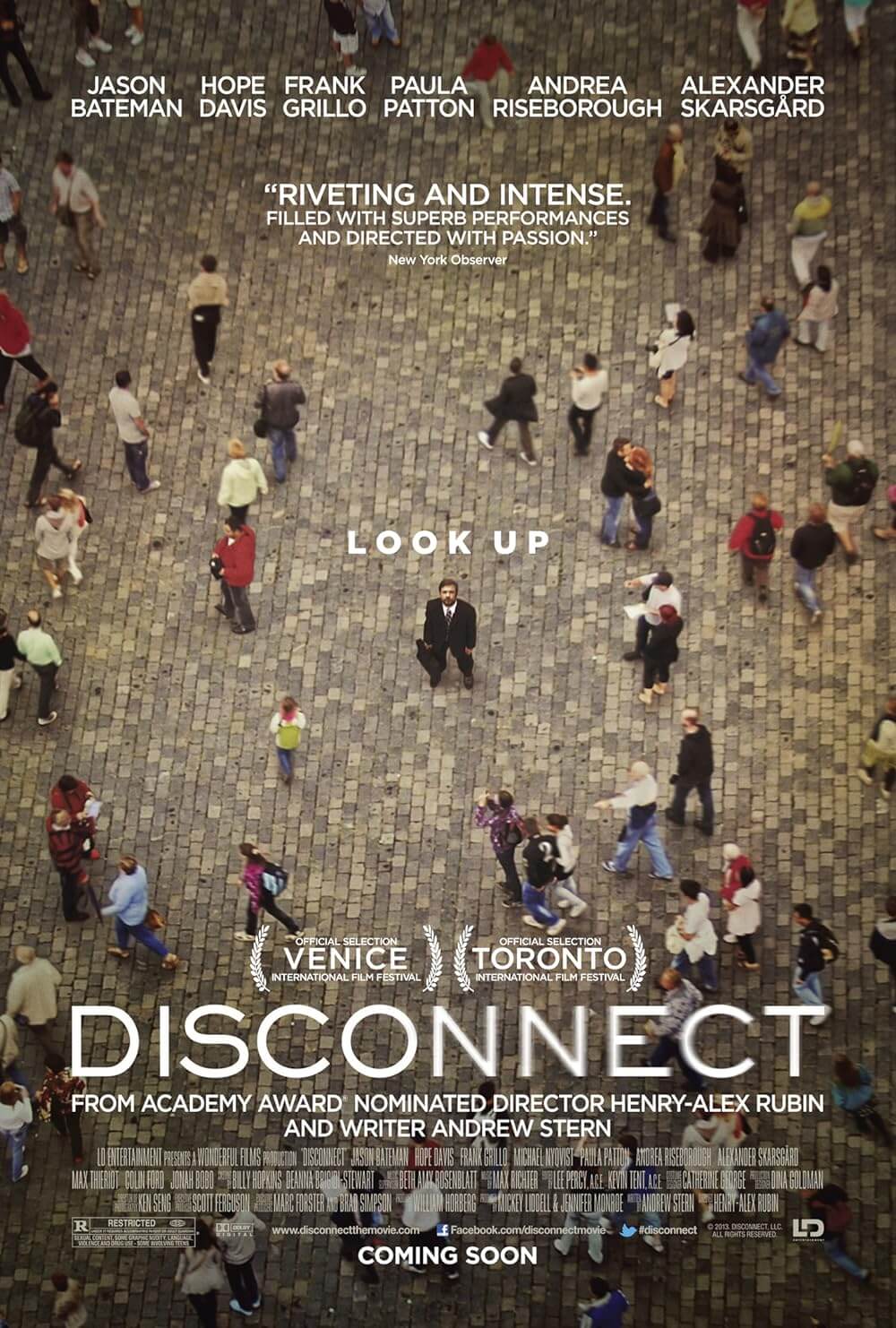

Go into any restaurant today, and you’ll find a couple sitting together, their eyes looking not at each other but directed down at the glowing screens of their smartphone, iPad, laptop, or what-have-you. They sit there together, but they’re miles apart. The irony of technology which is designed to bring people together yet seems to keep them at a distance is readily apparent everywhere. This is the theme of Disconnect, a cautionary tale and character mosaic about people living in an age where social behavior is often shaped by technology and internet networking. Directed by Murderball documentarian Henry Alex Rubin as his first fictional feature, the screenplay by Andrew Stern considers three overlapping stories about people whose lives are shattered because they rely on technology instead of simply speaking to one another. Anyone who’s had an email misinterpreted or sought to extinguish their loneliness on a social media site or chat room understands the circumstances all too well. Rubin and Stern consider the consequences of this in a drama as relevant as it is powerful.

Introverted and lonely, Ben Boyd (Jonah Bobo) makes music that no one hears but his few Facebook followers. Among them is “Jennifer Rhony,” a phony profile created by two of Ben’s classmates, Jason (Colin Ford) and Frye (Aviad Bernstein), two boys with nothing better to do but play cruel practical jokes on unsuspecting victims. Their joke on Ben via their false Facebook profile goes too far in such a way that the results eerily mirror recent headlines. Ben’s father Rich (Jason Bateman) searches for answers as to what happened to his son by contacting “Jennifer Rhony” online, and Jason, guilty over what’s happened, responds somewhat honestly. Another seemingly lost teen like Ben is Kyle (Max Thieriot), an 18-year-old web model who sells time for private video sex sessions. Crafty but low-level reporter Nina (Andrea Riseborough) finds Kyle online and wants his story for an exposé; her interest in the swaggering Kyle becomes something more through their illusory relationship, and she quickly finds herself willing to risk her career on a fantasy. A similar false friendship grows between Cindy (Paula Patton) and her chat room confidant ‘fear&loathing’ (Michael Nyqvist); but all at once, Cindy and her husband Derek’s (Alexander Skarsgård) finances have been stolen by an identity thief. With little legal recourse and bills piling up, they resolve to find the suspect—‘fear&loathing’—themselves and confront him.

The natural ways in which these three intersecting stories connect over the course of two hours enhance the larger themes in Disconnect and represent a poignancy not felt in such a mosaic film outside of Robert Altman or Paul Thomas Anderson. Rubin doesn’t employ the technical whimsy of an Altman or Anderson mosaic, but his treatment of the characters is evenly dispersed and met with a staggering authenticity. Much of the film feels shot and edited with a recessive visual personality, until the end, when the mounting tension builds to a climactic moment of ultra-slow-motion and booming music. That we’re completely engrossed rather than put off by this sudden stylistic flourish is a testament to the power of the filmmaking. We believe these characters; their actions never feel contrived for the sake of grand overemphasis. When Rubin escalates his visual technique to match the emotional heights of what occurs onscreen, the sequence might be compared to the titular collision from Paul Haggis’ 2004 film Crash, oft-consider the most undeserving of all Best Picture Oscar winners. Such comparisons do Disconnect an injustice.

Where Crash used insignificant correlations between characters to bring a sense of meaning to the overwrought melodrama, this film avoids falling into such traps by concentrating on fewer connections and making each one purposeful. That Jason’s distant father (Frank Grillo) drives him to open up online through his concealed conversations with Rich is significant, insomuch that Grillo’s character is also the ex-cyber crimes detective taking cases on the side, Cindy and Derek’s, in fact. Rich, a powerful attorney for Nina’s news corporation, always has an ear or one eye on his cell phone. His wife Lydia (Hope Davis) tries to speak to him, but his responses are delayed, his attention diverted by the glowing screen. Moreover, as these characters become more and more affected by their reliance on technology, the moderation of what happens does not spoil the thematic weight by overreaching dramatically. Where other films of this kind bring their characters together through some all-encompassing act or disaster, Disconnect exercises a level of restraint that empowers the drama and underlines the message.

Shooting over shoulders, through windows, across streets, and peering into the lives of these characters is cinematographer Ken Seng, his camera both voyeuristic and intimate, reflecting the same qualities of the tech-based relationships on display. We also see conversations conducted through chat rooms and texts onscreen, almost like subtitles. The technique is a form-follows-function move toward closeness, yet keeps these characters at a distance or half in the frame, denoting how even through film, their lives are fragmented by technology. This isn’t a documentarian’s approach to drama, but a modernist’s view better associated with someone like Steven Soderbergh in one of his less commercial projects (2009’s The Girlfriend Experience comes to mind). But, as stated, the style is recessive and takes a back seat to Rubin’s ensemble cast, which is uniformly excellent, particularly Bateman in a rare dramatic performance and Riceborough in one of several strong recent portrayals. Patton and Skarsgård share a number of tender scenes, whereas teen actors Ford and Bobo show incredible range.

An independent production that premiered at the Toronto Film Festival in 2012, Disconnect is brilliantly acted and staggeringly emotional, and it leaves you feeling guilty for every text, email, and Facebook post made after viewing. As the film’s characters attempt to resolve their conflicts through various-sized keyboards or methods of artificial communication, we can relate to their inability to communicate clearly or meaningfully. It makes you want to shut down your cell phone and have significant conversations with people again. What’s more, Disconnect could have easily gone a step too far and felt as contrived as Crash or even Babel (a film in which culture and languages keep people at a distance); instead, it ends up conveying a similar message in an equally profound way as David Fincher’s The Social Network. This is a drama whose turns play out in confrontations and collisions we anticipate, but they’re also rendered with a poetic step back from the kind of operatic tragedy that would make such a tale unbelievable. The characters make decisions and arrive at their fates in ways that seem realistic and, given the importance of the message, for this, we must be thankful.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review