Dìdi

By Brian Eggert |

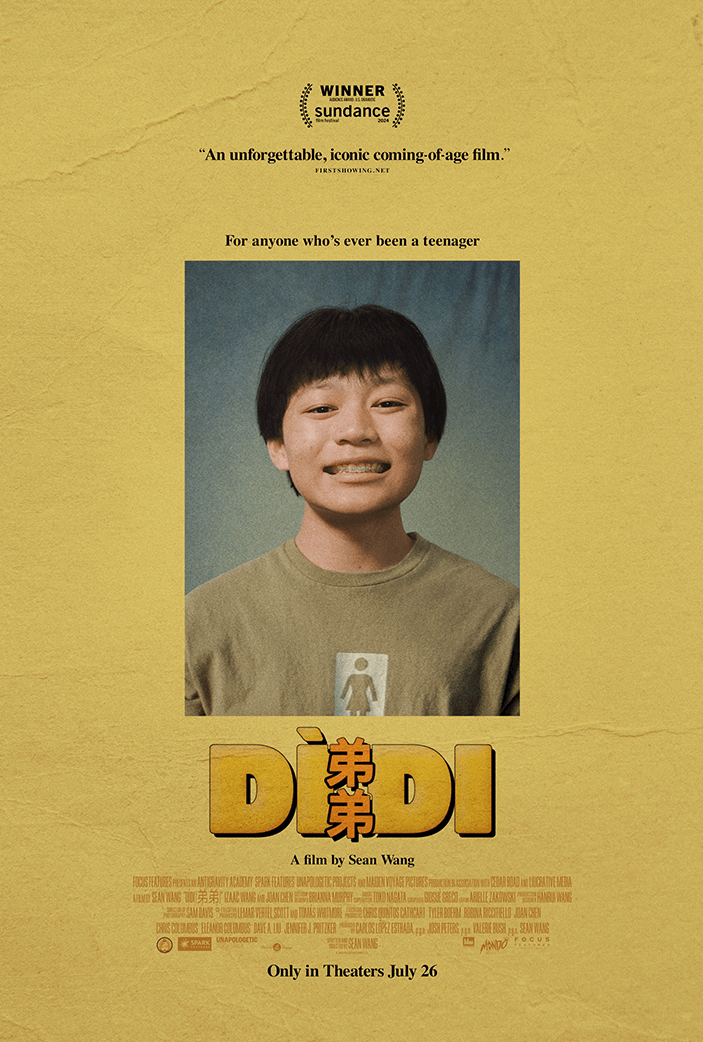

At a certain point, you have to wonder how many times you’ll see the same old coming-of-age movie. Each year, a slew of new entries in the genre arrive from filmmakers who want to share part of their adolescence. Most perform well because audiences love nostalgia and identify with the relatable hormonal stew and awkwardness on display. But every once in a while, one of these movies strikes a chord and epitomizes the experiences of a particular generation or social group, with examples ranging from The Breakfast Club (1985) to Mean Girls (2004) to Moonlight (2016). The list goes on and on. Even with the ubiquitousness of the genre, filmmakers keep telling these stories, and audiences keep seeing them. Look no further than the tagline on the poster for Dìdi (弟弟), Sean Wang’s semi-autobiographical debut and winner of the Audience Award at this year’s Sundance Film Festival: “For anyone who’s ever been a teenager,” it reads, summing up the broad appeal of coming-of-age movies. Indeed, these films keep getting made because we’ve all been there, and they’re a quick way to conjure empathy.

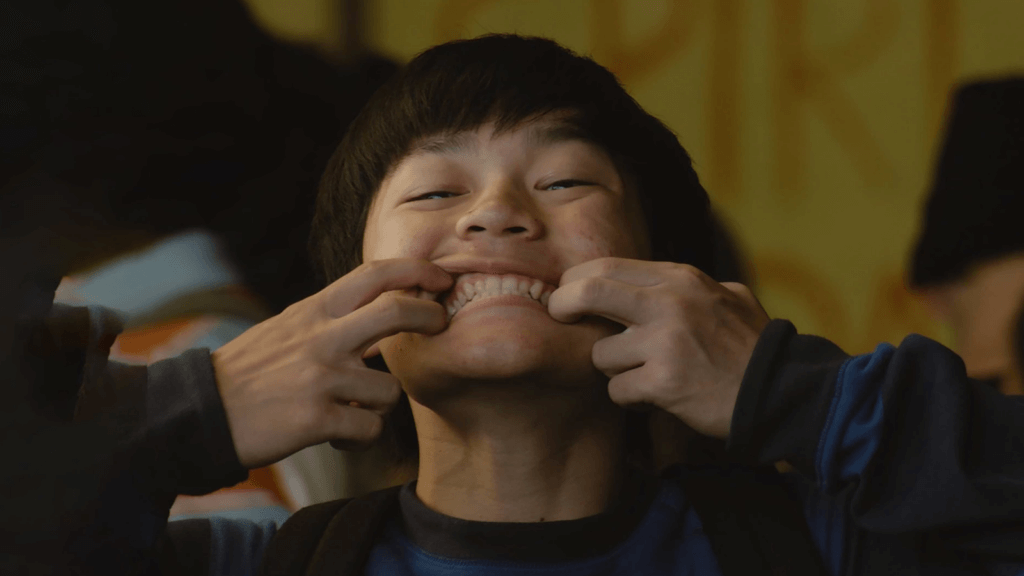

None of this is meant to degrade Dìdi for its conventionality or the commonplace status in the market. But apart from a few distinct details, Wang’s film adheres to the blueprint, and it serves its purpose as expected. What distinguishes it, and other films like it, are the particulars and personalities drawn from real-life experiences. The story follows Chris (Izaac Wang), a Taiwanese-American teen navigating the summer between junior high and high school. Speaking from experience, this is the age when some boys are at their worst. They can be perverted little jerks who say horrible things, behave like monsters, lie through their braces-laden teeth, and impulsively lash out at those closest to them. This is not a boys will be boys defense but an acknowledgment that, no matter how many coming-of-age films attempt to impart lessons learned from this age, many people learn too late that these behaviors are abhorrent. Later in life, one might look back at this time as a period of great regret, if not a sense of disassociation for who they were and how they behaved.

That seems to happen here with the writer-director, whose fictional counterpart, Chris, has the titular nickname at home. While his unseen father earns for the family in Taiwan, Chris lives with his aspiring painter mother Chungsing (Joan Chen), his college-bound sister Vivian (Shirley Chen), and his grandmother Nai Nai (Chang Li Hua). Although his parents seek the American Dream, Chris would be happy with finding some stable friends, perhaps even a girlfriend, or people he can be himself around. It doesn’t help that Chris often tries too hard, building himself up in desperate ways that reflect his alienation and insecurity. With the film set in 2008, the director deploys a desktop cinema view—like in Searching (2018) and Host (2020)—to show Chris crafting his online identity for Madi (Mahaela Park), a girl he likes. He checks out her Facebook and MySpace profiles and then uses that information on AOL Messenger to make himself appear to have more in common with her. This might be creepy in a different context; here, it just seems like a lost kid who needs to feel liked, even by a girl who tells him, “You’re pretty cute, for an Asian.”

Chris’ story might relay the origins of a juvenile delinquent or a particularly low chapter in the teen’s life, but Wang doesn’t flinch from giving an honest portrait. The effect is rather like Eighth Grade (2018), with Chris engaging in cringe-worthy behavior yet always maintaining the viewer’s sympathy. He participates in some pretty awful situations with his friend group of rambunctious, unthinking boys, including a nasty episode with a squirrel and a regular use of homophobic slurs. But he’s also fragile, showing sensitivity about his acne, but especially about his naïveté when it comes to interacting with Madi, giving way to an embarrassing moment that haunts him for the rest of the film. Later, talking to some older skater boys, he feigns experience shooting skateboarding videos and claims to be half-Asian—lies that, when exposed, leave only Chris to blame. Still, the film isn’t a series of humiliations and gaffes. Tender moments occur between Chris and his sister, who have a combative relationship until she realizes that her playful insults have gone too far.

Chris’ story might relay the origins of a juvenile delinquent or a particularly low chapter in the teen’s life, but Wang doesn’t flinch from giving an honest portrait. The effect is rather like Eighth Grade (2018), with Chris engaging in cringe-worthy behavior yet always maintaining the viewer’s sympathy. He participates in some pretty awful situations with his friend group of rambunctious, unthinking boys, including a nasty episode with a squirrel and a regular use of homophobic slurs. But he’s also fragile, showing sensitivity about his acne, but especially about his naïveté when it comes to interacting with Madi, giving way to an embarrassing moment that haunts him for the rest of the film. Later, talking to some older skater boys, he feigns experience shooting skateboarding videos and claims to be half-Asian—lies that, when exposed, leave only Chris to blame. Still, the film isn’t a series of humiliations and gaffes. Tender moments occur between Chris and his sister, who have a combative relationship until she realizes that her playful insults have gone too far.

Much of Dìdi entails Chris trying to figure out his social life, whereas his family is peripheral. Of course, every teen takes their family for granted, and Chris is no exception. But his family’s generational dynamics—from the nagging Nai Nai to the beleaguered Chungsing to the thoroughly Americanized children—factor into the conflicts, with Chris wanting to distance himself from their behavior. Nai Nai can be hilarious in her demands for Chris to eat or her irrational worry that every misstep will lead to his eventual ruin. But she can also be quite mean in her insults to Chungsing’s parenting. And as much as Chris attempts to distance himself from stereotypical Taiwanese behavior, he, too, speaks Mandarin. But he hides that part of himself from the kids at school. He wants to avoid earning nicknames like those he’s had in the past, such as “Wang Wang” or “Asian Chris.” Teens already feel different, and Chris doubly so. The writer-director accesses how this story is universal but specific, a standard way of describing most successful Sundance indies of this ilk. The more distinct its community, the more films like this seem to speak to everyone. It’s one of the weird little ironies of storytelling.

Dìdi weighs how the internet and social media amplify bad behaviors and insecurities among teens, making all those stupid choices—drugs, drinking, fighting, lying, and realizing too late that you’ve behaved awfully—all the worse. Its filmmaker understands how this 2008 era changed how children communicate and grow, seldom for the better. In that sense, Dìdi has an impressive authenticity, capturing how the internet looked then, the clothes kids wore, and the movies they watched. It does this without an overreliance on nostalgia or remember when situations, preferring to look critically at the past and Chris’ behaviors. Throughout, there’s an emotional immediacy and naturalism to the performances. Joan Chen shares a scene with her screen son late in the film that will prompt tears. Even so, Chris is a difficult character to like sometimes—certainly more disagreeable than Elsie Fisher’s role in Eighth Grade. But Dìdi watches this transitional chapter in his life close while another, decidedly more optimistic chapter begins.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review