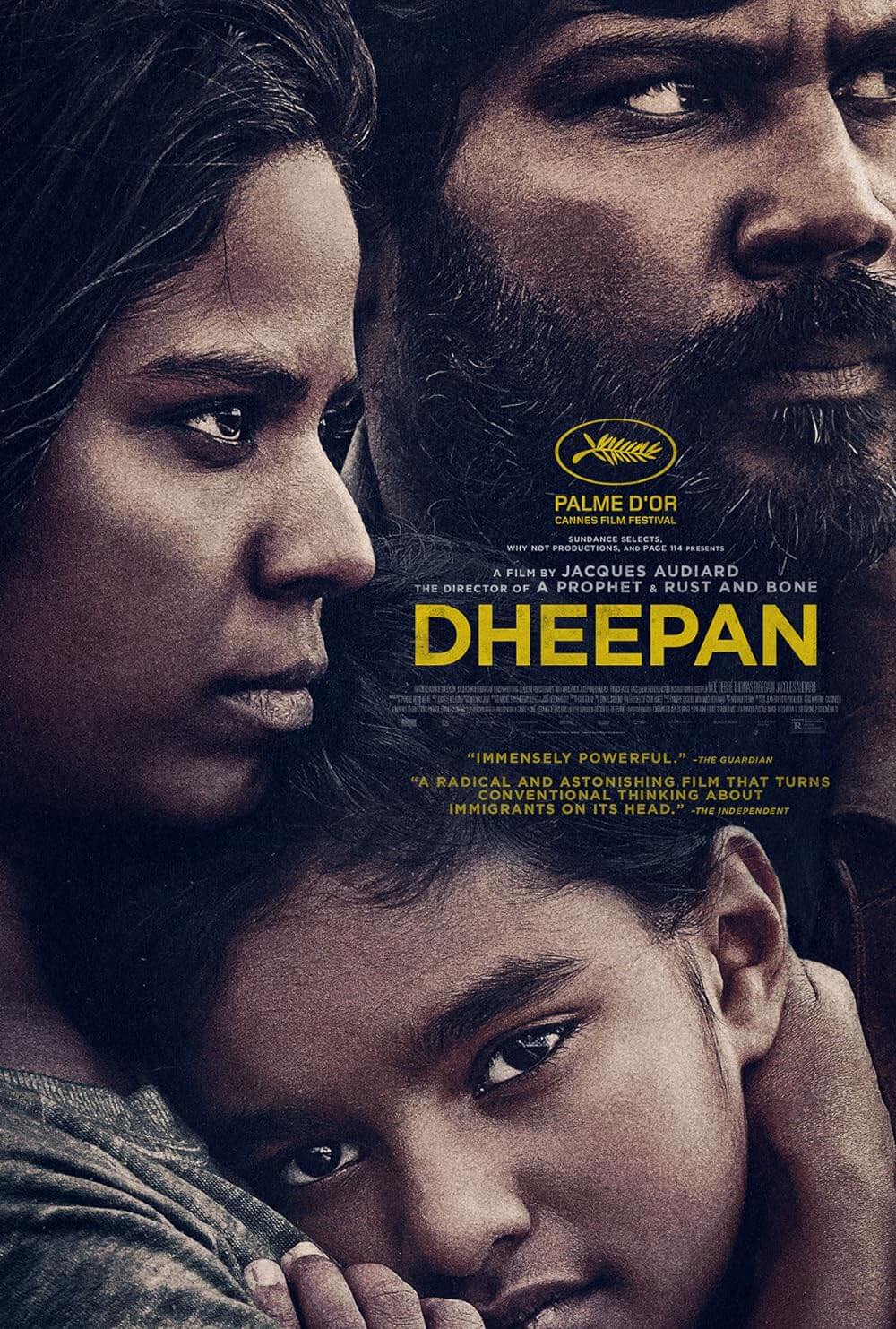

Dheepan

By Brian Eggert |

Jacques Audiard’s Dheepan asks its audience to see from another perspective, from faces and voices that seldom get representation in Western cinema. In 2015 when the film debuted, millions of immigrants the world over sought to escape the conditions of their native country for a better life. As the number of immigrants continues to increase across the globe, their destination countries resist and respond by politicizing people who seek a better life. The inability or unwillingness to see immigrants as human beings results in isolationism, racial profiling, intolerance, and religious persecution. Essentially, a lack of empathy. The French director recalibrates his viewpoint once again, as he did with a deaf woman on the fringes in Read My Lips (2001) or the Algerian criminal in A Prophet (2009). And like those films, his empathy extends beyond his national identity in Dheepan. Audiard offers compassion for his marginalized characters, refugees of the Sri Lankan Civil War and strangers living in a Western setting. His penchant for presenting uncommon worlds in convincing detail, and then twisting that detail with poetic flourishes and playful turns of plot, emerges in a beautiful if curiously hopeful outlook. It’s an odd film, to be sure, as it offers an imbalance of gritty realism, actionized catharsis, and dreamy resolutions.

In the frantic opening sequence, three immigrants in Sri Lanka scramble to make a boat to France. It’s 2009, at the end of the Civil War. Corpses lie everywhere, bodies burn, and the dusty refugee camps offer no solace. A former rebel militant of the Tamil Tigers, Sivadhasan, played by Antonythasan Jesuthasan, an unknown actor from the Indian subcontinent, takes the passport of a man named Dheepan. He realizes that his fellow soldiers of the local rebel militia face inevitable defeat by the government and, using the passports of dead locals, he escapes on a boat to France with a woman and a girl pretending to be his wife and child, Yalini (Kalieaswari Srinivasan) and the 9-year-old Illayaal (Claudine Vinasithamby). After a short time selling novelties on the streets of Paris, Dheepan and his impromptu family enter the social system, and before long, he receives a job managing a group of apartment buildings in a Paris banlieue dubbed Le Pré (the meadow, a lovely name for an awful place), their new home, a grimier and seedier version of the council estates in England. We experience Dheepan’s frustration as the new caretaker; he barely speaks the local language and must rely on Illayaal to translate basic instructions for how to clean and organize his building, one of many in the area.

Audiard and his co-writers, Thomas Bidegain and Noé Debré, place us into the perspective of his Sri Lankan characters. The drama feels enhanced even more from the point-of-view of someone who speaks neither fluent French nor Tamil, where every language onscreen is foreign and therefore equally relatable depending on the film’s subjectivity. In this case, the more foreign of the language is French, whereas the Tamil-language characters, the first introduced in the film, serve as our entry point. The writers imbue the relationship between the faux family members with subtle touches that deepen the characters. Our hero, marked by PTSD, stricken with grief over the loss of his actual family, begins to believe the lie, that Yalini and Illayaal are his family. The others are more realistic about their situation. Yalini, who becomes the personal cook for an Arab neighbor, never deludes herself and keeps her distance at first from both members of her makeshift family. She wants to escape to England, where she thought they were headed in the first place. Illayaal receives little emotional support from her would-be parents, though she yearns for approval as any child does. She’s aware of her estrangement from them, and yet she’s dependent on them. Even so, they become a family of sorts, bonding in their shared otherness, because who else is there?

At the same time, the Le Pré complex is a slum, overrun by a contingent of drug dealers, with just a smattering of poor citizens. Increasingly, their presence keeps Dheepan from his work and, given the language barriers, tensions grow. Their leader, Brahim (Vincent Rottiers), stations himself in his father’s apartment, where Yalini spends her days cooking and cleaning. Although neither of them speaks the same language, Brahim and Yalini talk to each other, making confessions that neither character understands, dancing around their mutual attraction. He’s more fracturable than he appears, while Yalini has hardened and resents her current station. Only the audience understands them both. But as the threat grows, Dheepan’s mental state wanes, and he becomes more convinced of his faux family’s authenticity, he responds in a way similar to what Travis Bickle did in Taxi Driver (1976)—his neurosis sharpens into a violent outburst aimed at the most available target, the local gangsters. The film takes a sudden, strange shift into an action film in its last twenty minutes. And though many have accused Dheepan of adopting a tone similar to Death Wish (1974), a troublesome film dripping with politicized bloodshed, Audiard’s hero has cracked beyond Charles Bronson’s mission of personal vengeance. Dheepan’s final march through Le Pré, complete with a machete-like blade and Molotov cocktails, represents an unleashing of human desperation and trauma that leads to a cryptic ending.

At the same time, the Le Pré complex is a slum, overrun by a contingent of drug dealers, with just a smattering of poor citizens. Increasingly, their presence keeps Dheepan from his work and, given the language barriers, tensions grow. Their leader, Brahim (Vincent Rottiers), stations himself in his father’s apartment, where Yalini spends her days cooking and cleaning. Although neither of them speaks the same language, Brahim and Yalini talk to each other, making confessions that neither character understands, dancing around their mutual attraction. He’s more fracturable than he appears, while Yalini has hardened and resents her current station. Only the audience understands them both. But as the threat grows, Dheepan’s mental state wanes, and he becomes more convinced of his faux family’s authenticity, he responds in a way similar to what Travis Bickle did in Taxi Driver (1976)—his neurosis sharpens into a violent outburst aimed at the most available target, the local gangsters. The film takes a sudden, strange shift into an action film in its last twenty minutes. And though many have accused Dheepan of adopting a tone similar to Death Wish (1974), a troublesome film dripping with politicized bloodshed, Audiard’s hero has cracked beyond Charles Bronson’s mission of personal vengeance. Dheepan’s final march through Le Pré, complete with a machete-like blade and Molotov cocktails, represents an unleashing of human desperation and trauma that leads to a cryptic ending.

For many critics, Dheepan‘s cynical and realistic portraits of immigration in contemporary France early in the film were followed by the incongruousness of the shoot-em-up finale, and the film’s unusual happily-ever-after ending in England. Audiard has said that he drew inspiration for the film from Montesquieu’s epistolary novel Persian Letters (1721), about two Persian men who leave their native country (modern Iran) to explore France, and sees the country from the eyes of an Other. The filmmaker also cites Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971), the notorious classic about a bookish American confronted by the base impulses of backwoods hillbillies on the English countryside. The film’s theme of a stranger in a strange and unfriendly land shows empathy for the immigrant travelers, portraying their journey as a violent one both in physical and psychological terms. And so, perhaps some viewers were being too literal about their interpretation of the final scene of Dheepan. After all, Audiard and cinematographer Éponine Momenceau blend poetry and realism throughout. Consider the repeated shots from Dheepan’s dreams of an almost abstract view of an elephant, a vague remembrance and symbol of home (as though his unconscious mind thinks in Orientalist imagery). In the same slow-motion, moody style, Dheepan and his cheery family appear together in the final shot, his new child with Yalini in her hands, surrounded by friends in their quiet suburban home. Whereas some take this scene to be an idyllic violation of the film’s unflinching sense of reality toward immigration, it seems instead to originate in Dheepan’s mind, where the elephants are.

Dheepan premiered at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, where Joel and Ethan Coen’s jury, which included members Guillermo del Toro and Xavier Dolan, awarded Audiard’s film with the Palme d’Or. It was a decision that has since been questioned, next to competitors like Todd Haynes’ Carol, Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Assassin, and László Nemes’ Son of Saul. But the relevance of the subject matter and the urgency of the filmmaking cannot be denied. Not often does representation from the perspective of the refugee occur in cinema. However, Audiard manages to force viewers from so-called First World countries to empathize with those who seek asylum or wish for a better life, while also reminding us that many Western cities run rampant with crime and gun violence. Dheepan and his family, real or not, face many of the same challenges from their old world in their new home. Audiard seems to argue that such is the tragedy of immigrant peoples, who try to escape one set of horrors only to be thrust into a system that produces another set. Dheepan is, ultimately, a film that calls for human understanding. Though its measured and even lyrical approach takes an unexpected, and brief, maneuver into the ultra-violent, it settles in a somber place. That Dheepan’s fantasy of family, friends, creature comforts, and suburban peace seems outlandish and dreamlike speaks to Audiard’s ability to portray our violent world with such veracity that anything else proves absurd.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review