Demolition

By Brian Eggert |

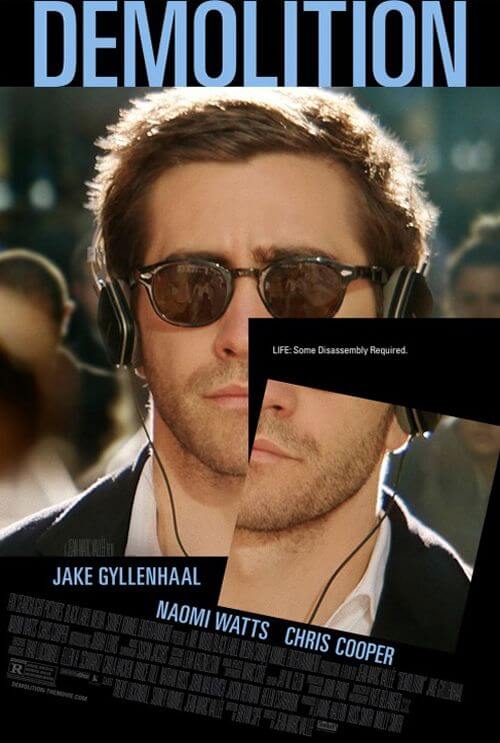

After his wife dies, Davis receives some advice from his father-in-law-turned-boss: “If you want to fix something, you have to take it apart and put it back together.” In Demolition, the main character takes this advice literally. Davis begins to tear down his home and destroy his belongings. Amid the wackiness, director Jean-Marc Vallée means to project something profound, this being his third Oscar-baiting film in a row after The Dallas Buyers Club and Wild—two films relying on similarly obvious metaphors to propel their dramatic turns. By breaking down the protagonist and building him back up again, in both literal and figurative ways, the film explores its subject from a measured distance, drawn only by an unsteady mix of satire and emotion. At times unpredictable and funny, Vallée’s few inspired flourishes fall short of transcending the story’s obviousness and sudden ending, despite a strong central performance by Jake Gyllenhaal.

The screenplay by Bryan Sipe borrows much from American Beauty. Jake Gyllenhaal plays Davis Mitchell, a disaffected investment guru who loses his wife to one of those shocker car crashes Hollywood is so fond of lately (Adaptation and No Country for Old Men feature great examples). Afterward, Davis, who admits he’s been numb to any feelings for well over a decade, follows a path to finding himself that has curious parallels to the characters to American Beauty, now a painfully outdated Oscar-winner for Best Picture: he gravitates to a lower-class job, he finds solace in homosexual friends, he befriends a teenager, and he offers us idiosyncratic voice-over. Hell, Demolition even co-stars Chris Cooper, whose role in American Beauty was another domineering father figure bound to traditionalism, but aching for something more real.

Rather than true narration, we learn Davis’ inner thoughts from a series of letters he writes. In the hospital after the crash that killed his wife, Julia (Jennifer Lind, seen almost entirely in wistful, impressionistic flashbacks), Davis tries to buy some candy, but the vending machine malfunctions. He proceeds to write a letter to the vending company, expounding his current situation in all the woeful details. Customer service rep Karen Moreno (Naomi Watts) reads Davis’ letters and calls him, at 2 a.m. no less, with a sympathetic ear. There’s a long, pleasant sequence where Davis pursues a face-to-face with Karen, until eventually they become friends, perhaps with the promise of more. In the meantime, Davis befriends Karen’s rebellious son, Chris (Judah Lewis), who likes classic rock and blowing things up.

“For some reason, everything has become a metaphor,” Davis admits. So, too, does everything in the film. Davis begins taking things apart and even volunteers his time with a construction crew that tears down old houses. He welcomes physical pain, and elicits Chris to help him tear down his own house. But after Davis drives a bulldozer into his living room, the wildly inconsistent film never acknowledges what happens after the bulldozer stalls; instead, there are random montages where Gyllenhaal dances in the street and takes his appliances apart. It’s all a rather obvious metaphor for the grief process. All the while, Vallée interrupts the forward motion with frequent, jagged flashbacks of Julia, which offer less than an inkling about Davis and Julia’s marriage. We never get a complete idea of why Davis hasn’t felt anything for years. What matters is how Davis works through his grief and begins to feel again.

For his fans, Gyllenhaal’s excellent performance will justify the entire experience of Demolition, heavy-handed metaphors and all. But even the most devout fans of the actor will scoff at how Davis exchanges his materialism for tools of wreckage and devastation. Despite the title, Vallée’s film is far too concerned with its protagonist’s downswing than his upswing. To be sure, the film wraps up Davis’ grief all too easily, piecing together a conclusion that leaves several subplots unresolved. On the whole, Demolition feels like a lesser version of better films such as The Weather Man (2005), in which Nicholas Cage’s disenchanted meteorologist starts carrying a bow and arrow to work. No matter how quirky or predictably unusual the protagonist’s behavior, it must connect to the viewer through an emotional payoff—something this film fails to do.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review