Death on the Nile

By Brian Eggert |

Agatha Christie wrote a Hercule Poirot mystery almost every year for much of her career. The most famous remains Murder on the Orient Express, published in 1934, followed by Death on the Nile three years later. Director Kenneth Branagh adapted the former into a respectable feature in 2017. With his second Poirot adaptation, he returns to Christie’s iconic Belgian sleuth, playing the ornately mustachioed fusspot detective with particular glee. Doubtless, Branagh was also attracted to the scenery, which exchanges a majestic train snowbound in Croatia for an elegant riverboat in Egypt. Whereas other Poirot mysteries unfold at dinner parties or the estates of wealthy victims, these two blend exotic, mobile locales with the author’s tendency for colorful characters and tightly wound plotting. It’s cinematic material, and Branagh recognizes its visual potential, but he overuses his digital toolkit. And while viewers might have known about the ending of Murder on the Orient Express out of sheer cultural osmosis, Death on the Nile’s mystery might deliver more intrigue for those unfamiliar.

There’s a long history of Christie adaptations for the big and small screens. Before Branagh tackled it, Christie’s Death on the Nile was made into a memorable film in 1978, featuring Peter Ustinov as Poirot and a supporting cast of Maggie Smith, Angela Lansbury, Bette Davis, and David Niven, among others. Branagh’s take appears lavish and expensive, putting attractive people in stunning environs. The Egyptian setting and moneyed company will also appeal to those drawn to the exhibition of wealth, even while Poirot alternately critiques their extravagances and relishes the many pleasures of vanity. Then again, much has been written online about the problematic members of the cast (Armie Hammer, Leticia Wright, and probably others in the time it takes me to finish this sentence). Without getting into the choices Hollywood performers sometimes make, the ensemble consists of lesser caliber actors than those who performed in Branagh’s Murder on the Orient Express. Instead of an all-star roster of marquee stars, the players include a few notable names and some faces the average moviegoer may recognize. Not that it matters; Branagh saves the juiciest role for himself.

In typical Christie fashion, the story finds several family members, lovers and former lovers, business partners, and acquaintances stuck on the same boat with “enough champagne to fill the Nile.” Everyone’s celebrating the marriage of the wealthy Linnet Ridgeway (Gal Gadot) and Simon Doyle (Hammer)—that is, except Jacqueline de Bellfort (Emma Mackey), Simon’s former fiancée. Then, of course, someone ends up dead, and everyone’s a suspect: Linnet’s quiet assistant (Rose Leslie); jazz singer Salome (Sophie Okonedo) and her manager (Wright); Linnet’s socialist godmother (Jennifer Saunders) and her nurse (Dawn French); Linnet’s lawyer (Ali Fazal); Linnet’s former fiancé, Dr. Windlesham (Russell Brand). Poirot’s trusted friend Bouc (Tom Bateman, reprising his role from the previous film) even appears with his cantankerous mother (Annette Benning) in tow. And while Branagh’s ostentatious and affecting character—charming here in his nervous attempts at flirtation with Salome—steals the show, the excellent turns from Gadot, Okonedo, and Bateman support him.

Branagh launches into Death on the Nile with his distinct brand of sensationalism. When he first started as a filmmaker, the director brought new life to several Shakespeare plays and rendered Dead Again (1991) and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994) with relentless pacing. He returned to that whirlwind momentum for Murder on the Orient Express, a production filled with punchy humor and editing. But like its predecessor, there’s a distracting amount of CGI used to create the Egyptian surroundings in Death on the Nile, with UK-based soundstages and Morocco standing in for the real thing. Compared to Branagh’s down-to-earth Belfast, which just opened late last year and earned several Oscar nominations, including Branagh for Best Direction and Best Original Screenplay, this feels like a hollow confection engineered on a computer. Interiors look convincing, but the digital skies and virtual camera movements mark a sharp contrast, leaving visual anachronisms for those used to seeing Poirot acted by David Suchet at actual locations. From the pyramids of Giza to the temples of King Ramses II at Abu Simbel, Branagh and cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos (the director’s collaborator since 2007’s Sleuth) create an artificial world, albeit accented with intermittent pleasures—the soundtrack of jazz and blues tunes, in particular. Still, the director applies his early career capacity for narrative thrust into the proceedings, keeping the 127-minute runtime plugging along.

Branagh launches into Death on the Nile with his distinct brand of sensationalism. When he first started as a filmmaker, the director brought new life to several Shakespeare plays and rendered Dead Again (1991) and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994) with relentless pacing. He returned to that whirlwind momentum for Murder on the Orient Express, a production filled with punchy humor and editing. But like its predecessor, there’s a distracting amount of CGI used to create the Egyptian surroundings in Death on the Nile, with UK-based soundstages and Morocco standing in for the real thing. Compared to Branagh’s down-to-earth Belfast, which just opened late last year and earned several Oscar nominations, including Branagh for Best Direction and Best Original Screenplay, this feels like a hollow confection engineered on a computer. Interiors look convincing, but the digital skies and virtual camera movements mark a sharp contrast, leaving visual anachronisms for those used to seeing Poirot acted by David Suchet at actual locations. From the pyramids of Giza to the temples of King Ramses II at Abu Simbel, Branagh and cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos (the director’s collaborator since 2007’s Sleuth) create an artificial world, albeit accented with intermittent pleasures—the soundtrack of jazz and blues tunes, in particular. Still, the director applies his early career capacity for narrative thrust into the proceedings, keeping the 127-minute runtime plugging along.

After just one Poirot film, Branagh has deconstructed his character. A World War I prologue before the murder mystery proper supplies an origin story to Poirot’s mustache. It’s like the opener in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) that explained Harrison Ford’s chin scar—or perhaps more accurately, the titular character in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), who hid a facial scar behind his walrus mustache. The sequence is shot in black-and-white and features a de-aged Branagh; it even recalls Joel Coen’s recent foray into Shakespeare with The Tragedy of Macbeth, complete with CGI ravens and fog. (There’s a lot of CGI in Death on the Nile, especially of the animal variety: a snake escapes its charmer and leaps at the viewer; a Nile crocodile snaps at some prey; a fish nips at a submerged handkerchief.) But the early sequence establishes the film’s melancholy mood of lost love, which carries through to multiple characters but mainly gives Poirot dimension. Those few small moments where Branagh portrays his character’s remembrances and how he used to love transform Poirot into more than a mere OCD detective.

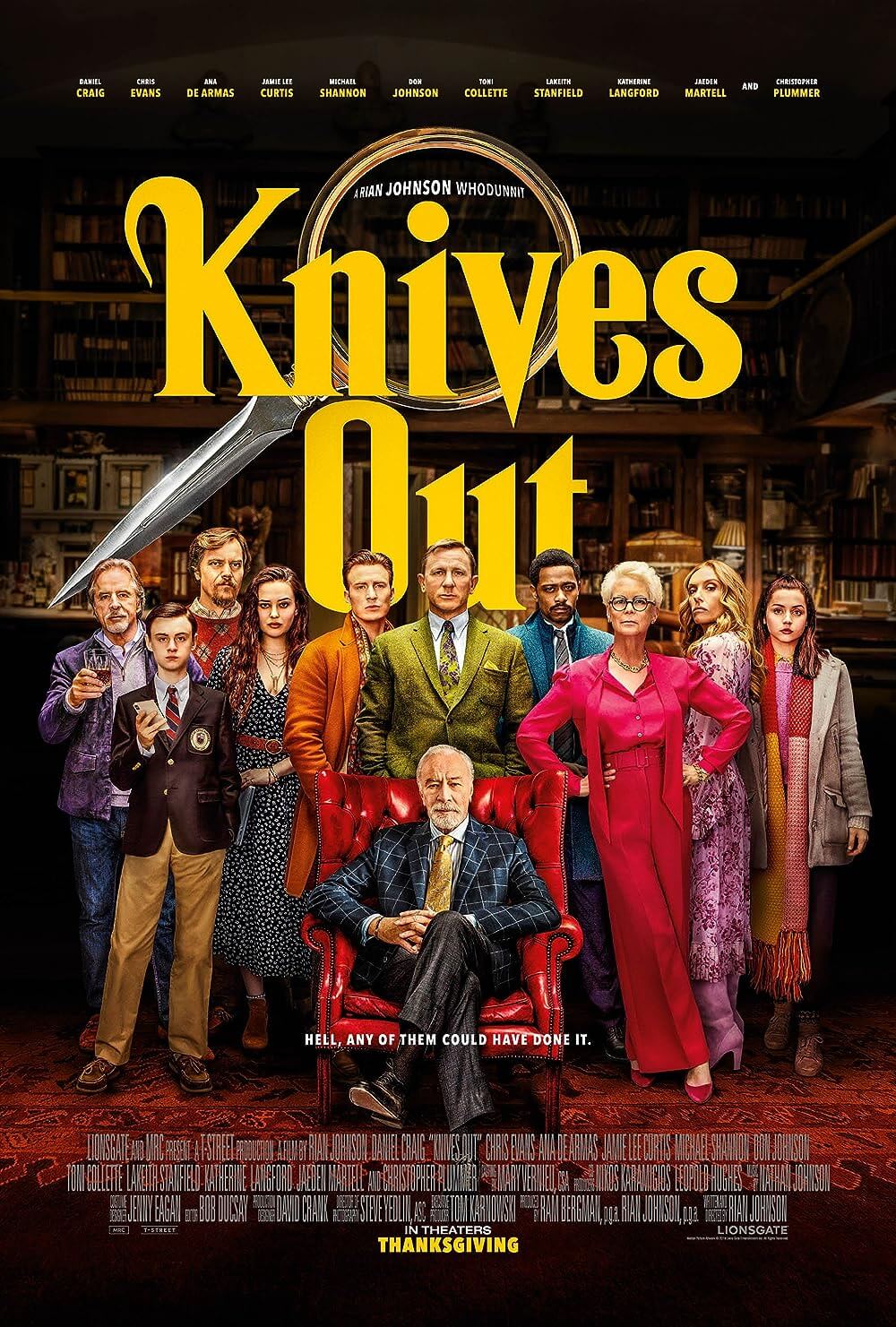

Death on the Nile has been moved and reshuffled on the release calendar since 2019, after delays caused by both the pandemic and Disney’s takeover of 20th Century Fox (now 20th Century Studios). Moreover, two years after Branagh reintroduced the world to Christie, Rian Johnson delivered his postmodern take on the whodunit with 2019’s superb Knives Out. After Johnson turned every Christie convention on its head, the mystery of Death on the Nile feels commonplace. Branagh and screenwriter Michael Green keep to Christie’s standard structure (setup, murder, interviews, and resolution), but the best moments deviate and allow Poirot to exist as a human being. Few characters in the film feel like more than archetypes playing out their assigned roles. When Branagh enables them to be more, the movie provides a diverting yarn. Whatever its visual missteps, the storytelling manages to grab hold—and so if Branagh keeps exploring Poirot’s adventures, I’ll keep watching them.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review