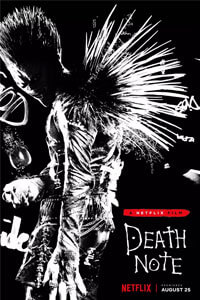

Death Note

By Brian Eggert |

Death Note, the manga by Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata, first published in the pages of Shonen Jump between 2003 and 2006, launched a popular Japanese franchise consisting of novels, an anime series, three live-action films, videogames, and other media. The intellectual property’s translation into an English-language feature, released as a Netflix Original, boasts a respectable mid-level budget, high production values, and a stylish visual approach. Adam Wingard, the independent horror director behind You’re Next (2011) and The Guest (2014), and fresh off his underwhelming detour in last year’s sequel Blair Witch, helms the new version of Death Note. Unfortunately, the film follows a recent string of Hollywood productions that cast white actors in the roles of non-white characters, and its vocal detractors have spoken out. But the casting is less of an issue than the poor transition from a story entrenched in Japanese culture to its new Western skin that, throughout many aspects of the film, still feels like a Japanese story only with American actors.

Death Note has been accused of whitewashing its cast. The mob mentality of our outrage culture often suggests that every role needs to be played by a performer who embodies the race and gender associated with their character. However, color-blind casting choices should be met with a level of open-mindedness in terms of what each film hopes to accomplish. After all, Idris Elba recently played the traditionally white gunslinger in The Dark Tower; Matt Damon and Leonardo DiCaprio starred in The Departed (2006), an update of the 2002 Hong Kong thriller Infernal Affairs; and the Broadway production Hamilton cast a multicultural list of performers in historically white roles. In these cases, casting against racial type worked because either the role or story wasn’t so race-specific to begin with, the material was translated with its story intact but a shift in the cultural backdrop, or the performances in question were strong enough to overcome any incongruities.

Perhaps we should be more open to talk about and understand the casting in the film’s context, and then look at these issues on a case-by-case basis, rather than making a sweeping denouncement before examining the finished film (that last part, about letting filmmakers get their film complete before protesting, is important). Too often critics and social media currents dwell on these extra-textual elements of what we know about the previous versions, what source materials intended for its characters, and how the character should look. Shouldn’t we be more concerned with the new vision, and how well the filmmaker’s choices, both in terms of narrative and casting, play out in the finished product? For instance, an argument could be made for Hollywood’s controversial adaptation of the Japanese anime Ghost in the Shell, starring Scarlett Johansson, as the film told a story set in a futuristic, multicultural melting pot, and its cast hailing from various ethnic backgrounds seemed appropriate within the film’s context. But so many people were incensed by the casting choices that they didn’t bother to see the film for themselves. The combination of close-mindedness and opinions that function on a polarized scale do not make for good, healthy discourse about what’s happening in our culture.

After all, we’re all human beings and, in a way, limiting certain roles to certain races perpetuates the differences between us. Then again, there’s something to be said about the values of an industry that consistently attempts to cast white actors in non-white roles and marginalizes female talent. The regularity of this issue is what raises alarms among our increasingly sensitive culture—and we have become increasingly, sometimes overly sensitive, but not without good cause. It’s alarming to think these casting trends are embraced by Hollywood because that’s what sells. And if so, is this just another sign of white-male privilege in Trump’s America rearing its ugly, bloated, orange head? Could the whitewashing of performers represent yet another symptom of a fascist ideology perpetuated by white supremacists? No matter where you stand on this issue, there are strong counterpoints. Perhaps you’re sympathetic to filmmakers and their representational choices, or perhaps you want to avoid any risk of supporting a conscious or unconscious trend in Hollywood.

In either case, there’s no easy solution to be found, certainly not in Death Note, a film that has been moved from Japan to the U.S. if only to make an easier sell to subtitle-resistant viewers. The film’s cast of characters received instant accusations of whitewashing when the players were announced. Paper Towns (2015) star Nat Wolff plays Light Turner (originally named Light Yagami), a Seattle teen of above-average intelligence who finds a leather-bound book that gives its owner the ability to kill anyone simply by writing their name in its pages. The book has dozens of rules (though we learn only a handful), enforced by the book’s overseer, Ryuck, a porcupine-looking death god who, voiced by Willem Dafoe, resembles a monochrome version of The Joker. The largely practical effects used to bring Ryuck to life, compared to the laughable CGI in the Japanese live-action films, is the new Death Note‘s best feature. Ryuck is creepy as hell.

Without much hesitation, Light tests the book’s capabilities by disposing of a school bully and the gangster responsible for his mother’s death, their deaths achieved through gruesome accidents. He’s soon joined by his darkly inclined classmate and love interest, Mia (Margaret Qualley), and the two engage in a series of corrective murders the world over, all from the relative safety of Seattle. (If themes of godly power and moral justice weren’t enough, consider the availability of fresh apples, the forbidden fruit itself, in Light’s home, and how Ryuck, a demonic beast with glowing eyes, chows through them.) To avoid suspicion, they concoct a ridiculous cover story to these otherwise random, unconnected deaths by attributing them to a vengeful god named “Kira”. Somehow (it’s never adequately explained), a mysterious and eccentric investigator called “L” (Lakeith Stanfield), who has silly mannerisms like standing on chairs, puts together Light and Mia’s scheme. Light could just kill L to avoid capture, but there’s a rule: the Death Note’s owner must be able to visualize the victim’s face, and L keeps his face covered with an absurdly pulled-up turtle-neck.

For the first half-hour as Light discovers the limits of the Death Note, the film maintains a tense, playful, supernatural tone. The excellent electronic score by Atticus and Leopold Ross gives the material that 1980s stylization that most Wingard films have. Cinematographer David Tattersall uses Seattle’s rain-soaked locations to atmospheric effect, saturating night scenes with a neon glow. It all leads to a climax involving a police chase and breathless dangling atop Seattle’s Great Wheel, and the entire sequence is set to Celine Dion’s “The Power of Love,” making it ironically funny. It also makes for an odd finale, but no less so than Ryuck’s final observation that “Humans are so interesting,” followed by abrupt end credits. What exactly Light was supposed to learn from the experience, if anything, remains obscure or perhaps entirely nonexistent.

For the first half-hour as Light discovers the limits of the Death Note, the film maintains a tense, playful, supernatural tone. The excellent electronic score by Atticus and Leopold Ross gives the material that 1980s stylization that most Wingard films have. Cinematographer David Tattersall uses Seattle’s rain-soaked locations to atmospheric effect, saturating night scenes with a neon glow. It all leads to a climax involving a police chase and breathless dangling atop Seattle’s Great Wheel, and the entire sequence is set to Celine Dion’s “The Power of Love,” making it ironically funny. It also makes for an odd finale, but no less so than Ryuck’s final observation that “Humans are so interesting,” followed by abrupt end credits. What exactly Light was supposed to learn from the experience, if anything, remains obscure or perhaps entirely nonexistent.

Quite simply, Death Note isn’t a story that makes much sense for American audiences (or anyone else for that matter), in large part because the material has not been properly adapted. So while Japanese viewers, who have dozens of deities in their culture, have no trouble reconciling the source material’s conceit of a mischievous death god or the notion that the world would accept Light and Mia’s “Kira,” these ideas make little sense to an American viewer watching the American adaptation. By contrast, watching the Japanese films or anime series, these creative choices fit, given the cultural context. Additionally, the deviations from the source material do not amount to a structure vision or purpose, leaving the tone and viewer’s level of engagement to suffer. At times the film feels like a dark comedy, a morality tale, or cat-and-mouse cop thriller. Wingard’s lack of control over the material seems unlike his work, and yet the uneven result speaks for itself.

Americanizing stories from other countries isn’t the problem, at least not the one surrounding the discussion of Death Note—even if that’s the prevailing conversation about the film. From the aforementioned The Departed to Spike Lee’s version of Oldboy, to the upcoming remake of last year’s Toni Erdmann, this trend is nothing new. The problem is not the whitewashing of actors (“whitewashing” is a particularly inappropriate term in this case since Stanfield is a person of color). The problem is how the script (by Charley Parlapanides, Vlas Parlapanides, and Jeremy Slater) resettles a Japanese story in America without completely reformatting the narrative’s details, or even the broadstrokes, to reflect an American culture audiences will recognize. Any question of nationalism, racism, or social irresponsibility in the production’s concept feels less essential than what the film itself has to offer. Sadly, that isn’t much.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review