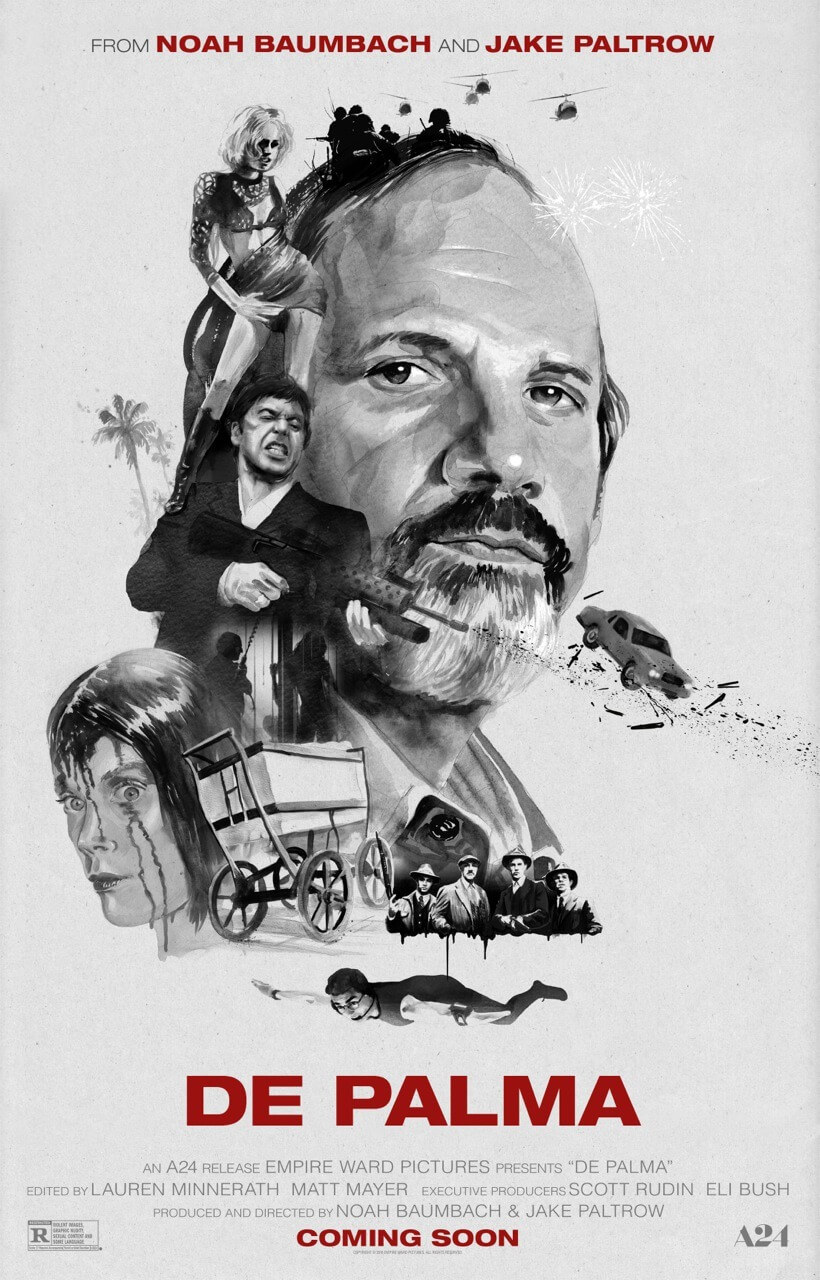

De Palma

By Brian Eggert |

Co-directors Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow each step outside of their comfort zone for De Palma, a documentary looking back on the 70-year-old Brian De Palma’s career. Baumbach’s sensibilities hardly suggest that of a De Palma devotee, since he’s mostly known for a string of blithe existential dramedies like Frances Ha (2013) and Mistress America (2015). Likewise, Paltrow’s underrated post-apocalyptic western Young Ones (2014) doesn’t reflect the filmmaking of a De Palma disciple. Nevertheless, both Baumbach and Paltrow remain cinema aficionados and apparent De Palma enthusiasts, delivering a simple interview-style retrospective of the virtuoso filmmaker’s life and career. The entire interview was apparently shot in one sitting, with the interviewers remaining off-camera and unheard, as this rather straightforward and linear account of De Palma’s proceeds with brief cutaways to their subject’s body of work.

De Palma fans probably could not imagine a more appropriate opening than the one conceived by Baumbach and Paltrow: a scene straight from Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), a film which, along with other Hitchcock pictures, has had immeasurable influence on the director. Indeed, the filmmaker often earns comparisons to Hitchcock, as well as accusations of barefaced theft from the Master of Suspense. Certainly several of De Palma’s scenarios borrow from Hitchcock, and he’s the first to admit it. For De Palma, Hitchcock engaged his audience by manipulating their gaze, creating an illusion that draws the viewer in, and once locked-in to the illusion, the director destroys that illusion and shatters his audience—such as killing the main character thirty minutes into Psycho (1960). As the documentary later shows, most of De Palma’s passion projects involve a similar, pointedly Hitchcockian dynamic. As De Palma talks about Hitchcock’s “influential” status, he wonders why other filmmakers aren’t more closely following him: “I haven’t seen that many people who actually follow his form except for me,” he chuckles.

Before digging into each of his twenty-eight features, the doc briefly touches on De Palma’s early life in a Quaker school, growing up alongside two brothers and under a father whose career as an orthopedic surgeon kept him distant from the family. De Palma later studied film at Sarah Lawrence, became closely acquainted with Robert De Niro and worked alongside the up-and-coming actor on their first films together, and soon joined the ranks of the New Hollywood film buffs of the 1970s (including Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, George Lucas, and Francis Ford Coppola). Once De Palma reaches a rhythm, just as the director remembers feeding lines to Orson Welles on his early low-budget project Get to Know Your Rabbit (1972), he proves to be a candid storyteller, recounting several memorable stories about working with actors and writers throughout his career.

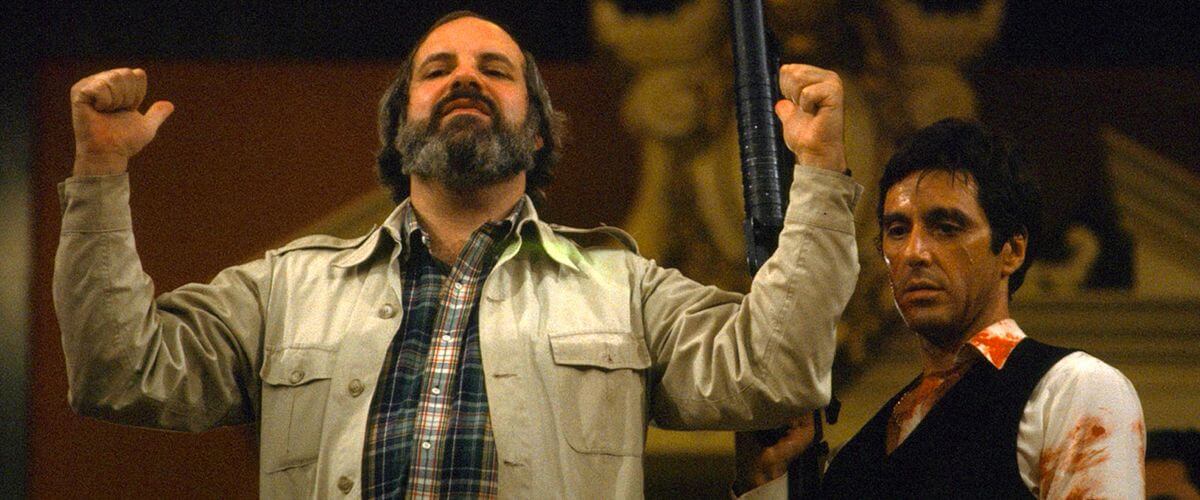

Whether he’s remarking on Cliff Robertson’s distractingly brown makeup on Obsession (1976) or recalling how he had to remove screenwriter Oliver Stone from the set of Scarface (1983), his stories are fascinating, sometimes providing new insight into a film, sometimes showcasing the filmmaker’s unexpected honesty about his work. Consider the way he dismisses The Fury (1978), his acclaimed follow-up to Carrie (1976), as conventional and not one of his favorites “by a longshot.” Or his original ending to Snake Eyes (1998). Or how he talks about his big-budget studio picture Mission to Mars (2000) like a lingering trauma. He also talks about his most commonly used devices, split-diopter lenses and split-screens, and how he hopes to challenge the viewer with a juxtaposition of images.

Perhaps the most interesting aspects of De Palma involve his dismissive discussions about censorship and his critics. If there’s a worthy criticism about De Palma, it’s that the doc does not thoroughly investigate how he’s been perceived. Throughout the years, critics have censured De Palma for his use of violence against women, violence in general, and perceived misogynist undertones to his films. Most apparent is the director’s desire to film his own ideas, not someone else’s. When Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer offered him the chance to direct the surefire hit Flashdance, he turned down the opportunity to helm Body Double (1984), for which he received his most heated bad reviews. “It all seemed very logical to me,” says De Palma, dismissing interpretations of the film’s phallic symbolism. It becomes apparent, though not outwardly addressed, that De Palma is not consciously or intellectually exploring his recurring themes; rather, his frequent themes often emerge unconsciously in his work. (Note: To make up for his critical bomb on Body Double, he tried something else: Bruce Springsteen’s “Dancing in the Dark” music video (!).)

The filmmaker’s concerns with technical and formal storytelling become apparent throughout De Palma. We hear story after story about how he begins with a sequence in mind and works from there. Addressing his off-screen interviewers, De Palma says, “You start with character and work your way outwards, while I start with construction and work my way in.” Having grown up as a student of science and winning several science fairs, De Palma demonstrates that he remains less interested in theory than exploring his own technical preoccupations, and putting everything in its right place as he sees it (which is not to suggest his films are devoid of thematic underpinnings and interpretable subtexts; quite the opposite—they are loaded). According to DePalma, he’s not consciously thinking about the meaning of his films, but rather exploring ideas about the nature of cinema, how Hitchcock would do it, and his ideas about what he wants to see in a film. For any De Palma fan or anyone interested in learning more, this doc is essential viewing. Through it, Baumbach and Paltrow infer that De Palma is about as “pure cinema” as it gets.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review