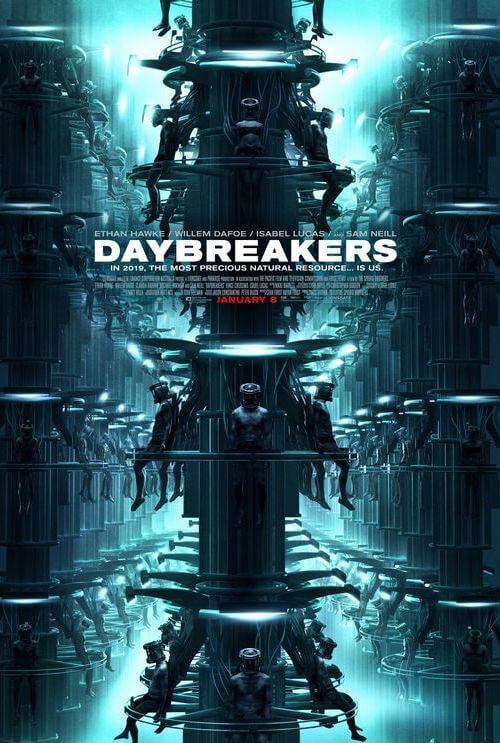

Daybreakers

By Brian Eggert |

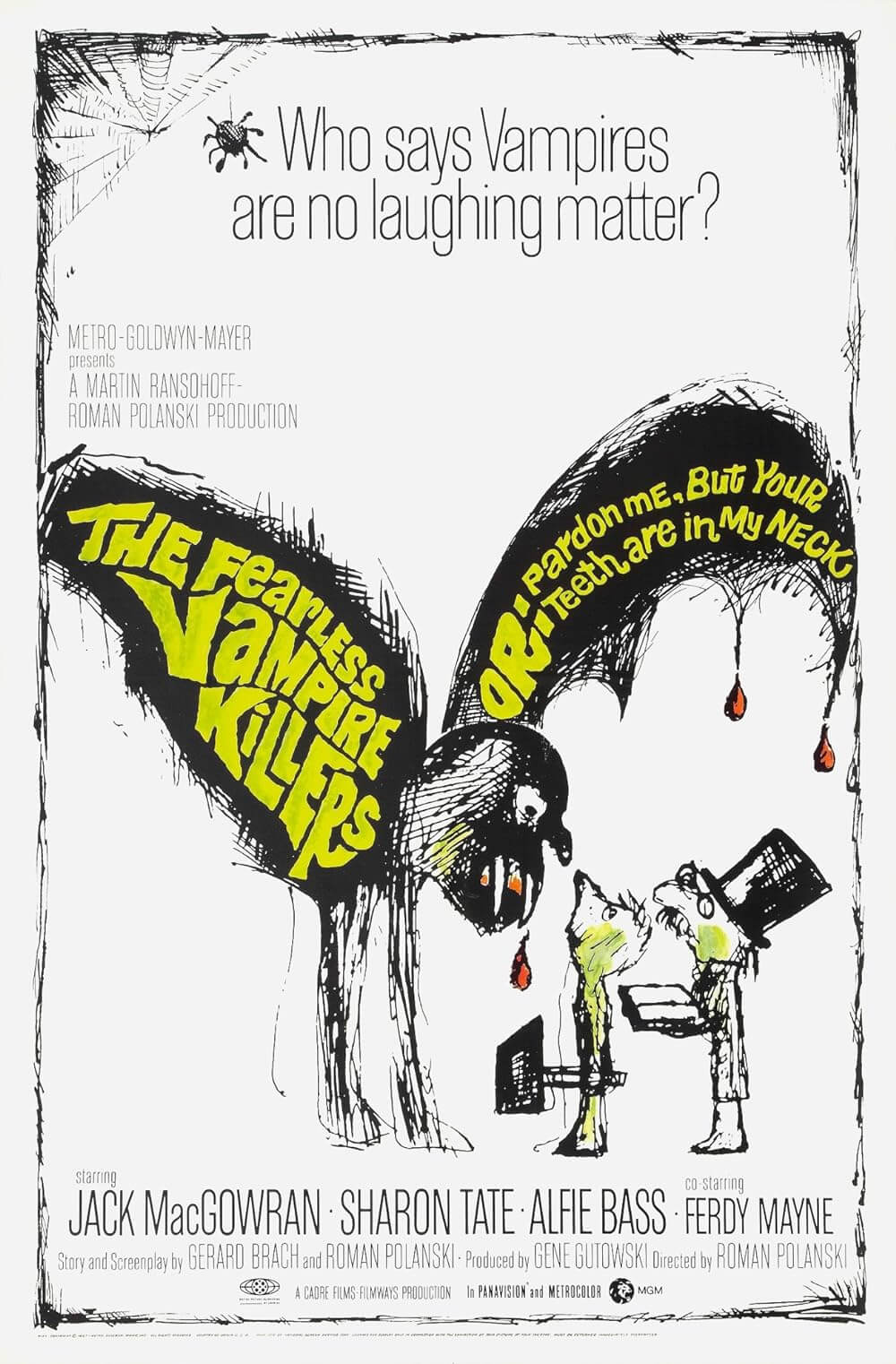

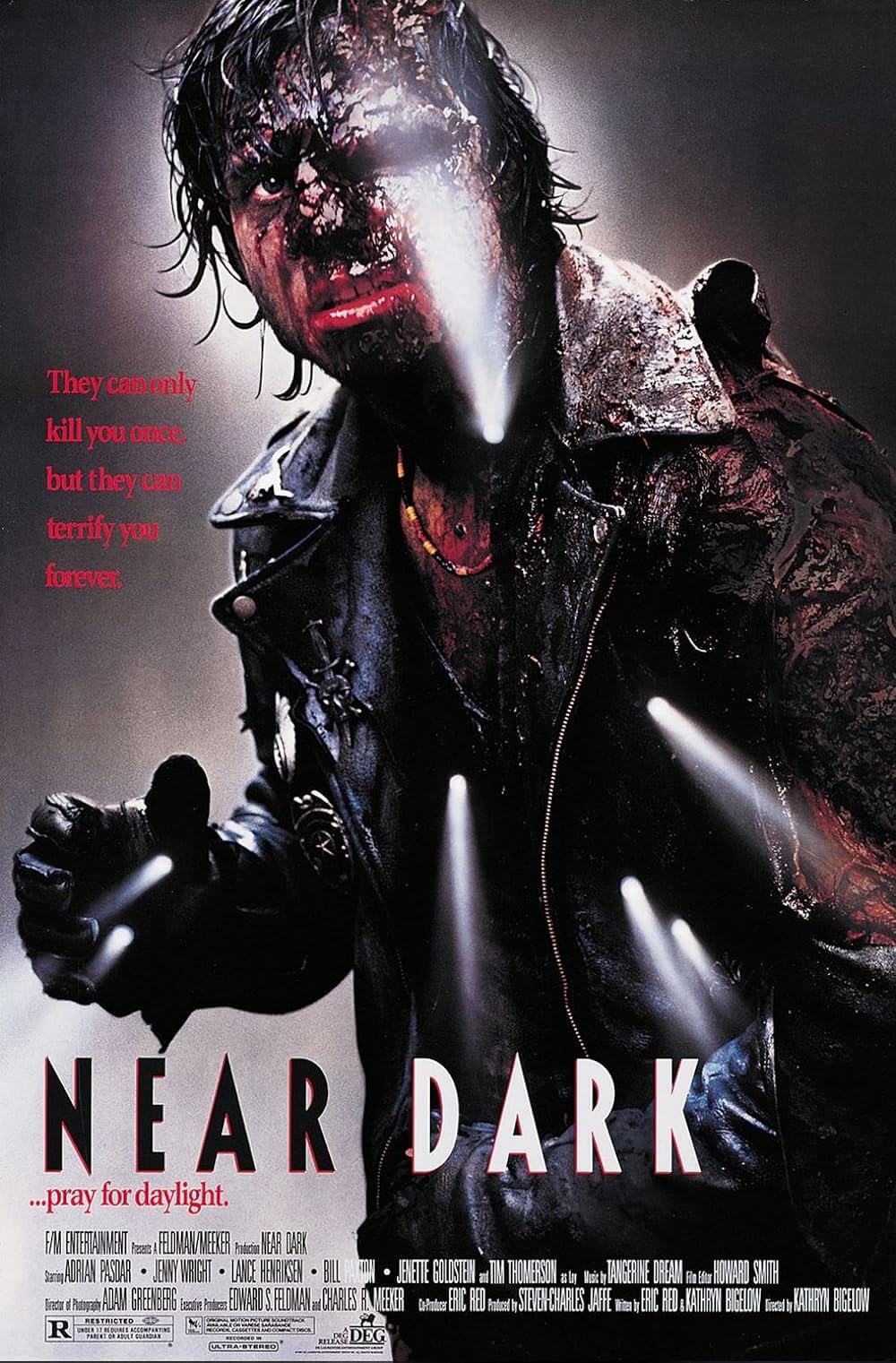

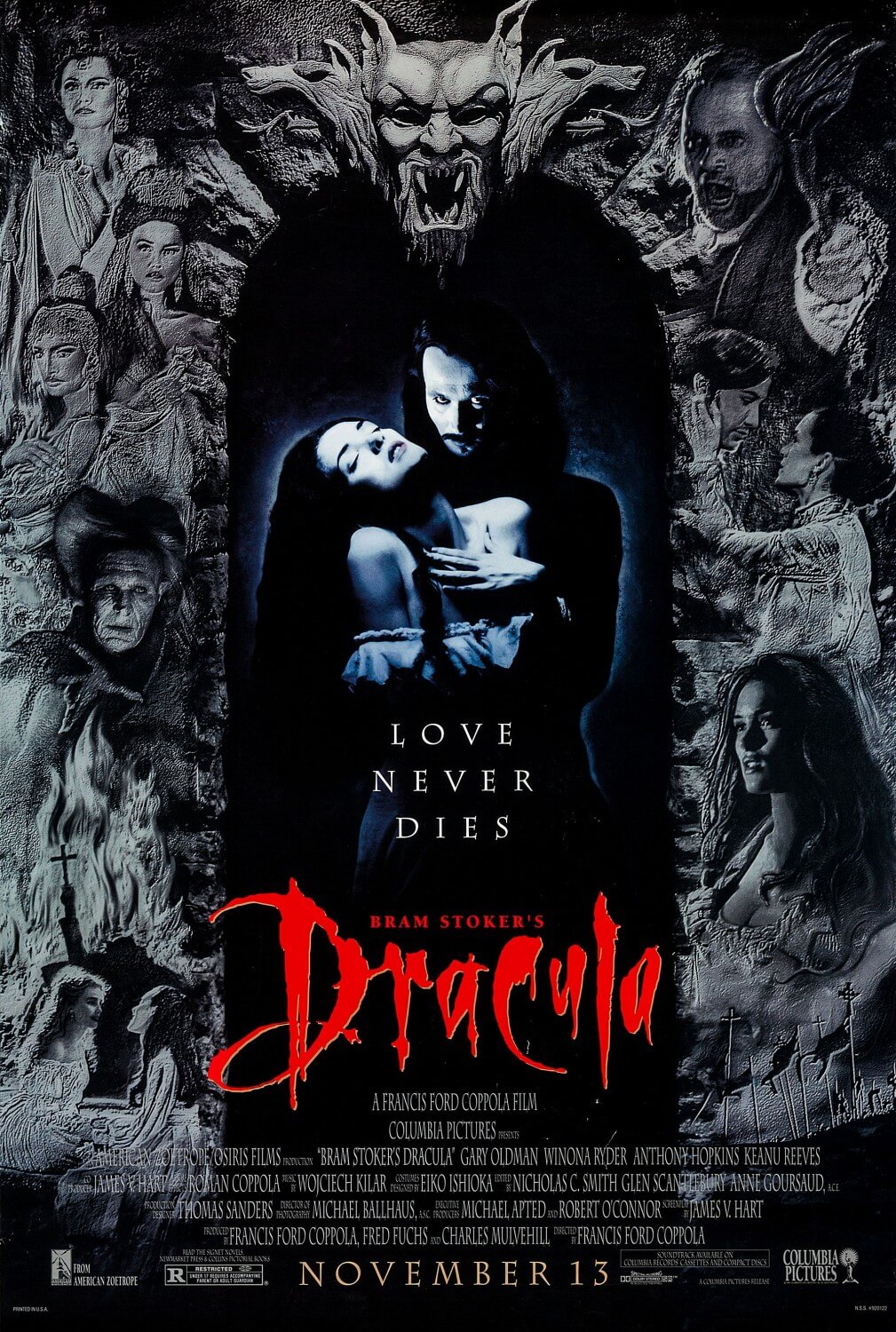

The surprising thing about Daybreakers, a vampire movie and the second feature by the Spierig Brothers, is that it isn’t just some actioner with fangs. There are an involving narrative and even an intelligent allegory within, and they exist in a meticulously conceived environment—believable even, or as convincing as it can be given the subject matter. Moreover, at a time in cinema when the vampire is overexposed, and in a sense de-fanged thanks to its softening by the Twilight series, the Spierigs help reestablish vampires into scary and socially reflective movie monsters.

The story begins in 2019 when for some time a vampire plague has spread throughout the world. The population is 95% vampire, and the other 5% are humans desperately hiding to avoid being captured and harvested for blood. In their rise to power, these reflection-less, scared-of-the-sun vampires have been ignorant about their resources. In other words, they’ve been sucking too much blood and now there aren’t enough humans to go around. The major corporate blood bank Bromley Marks, run by sinister tycoon Charles Bromley (a wonderfully devilish Sam Neill), farms humans, but their food sources are dwindling. Only enough humans remain to supply the vamp world with blood for another month.

Bromley Marks’ top hematologist, Edward (Ethan Hawke), toils to find a solution for the problem using synthetic blood, but he can’t crack the formula. Bromley wants to push synthetic on the masses to help replenish the human population, and then offer genuine human blood as a luxury to the elite classes. But Edward is sympathetic to the humans, having been turned into a vampire against his will; he’s stopped drinking human blood altogether. Not a good idea. Vampires starved from lack of blood intake turn into creatures called “Subsiders”—de-evolved batlike monsters that lurk in the sewers and slums, wherever the blood shortage is felt the most. It seems as though every vampire on the planet will eventually turn into Subsiders if the situation doesn’t improve. Luckily, Edward comes across a band of human rebels with a cure for vampirism.

The details of Spierigs’ vampire world are plentiful and well-considered. They’ve done a superb job of conceiving elements that can’t help but involve us in the save-the-world scenario. The audience has a sense of discovery throughout, with clever little features slowly revealing themselves as the movie progresses, helping to solidify our participation. Cars drive by day with dimmed UV-blocking shades, vamp children wait for their school buses in the middle of the night, and coffeehouses boast 20% blood content in their java. Even while the holes in the plot have the opposite effect, the construction of the movie’s environment keeps us fascinated.

Just as they did with their previous feature, 2003’s underwhelming Undead, the Spierigs’ completed the CGI animation themselves. However, the true visual marvel of the movie isn’t the computer effects, which mostly help complete cityscapes and the human farming machinery. The wonders are the abundant makeup work, everything from the hideous Subsiders to the use of fake blood has a potent tangible quality onscreen. So many movies today use computer-animated blood (see Ninja Assassin for buckets of the stuff that isn’t there) to save time and money, and they use the same tricks to render their creatures (see the Underworld series for some CGI vamps and werewolves). It costs a lot to clean up and reshoot a blood-splattered scene and employ makeup artists and have actors sitting in chairs for hours on end. So the authenticity of the blood and monster effects throughout the film is appreciated.

Besides the impeccable design of the setting and genuine special FX, the writer-director brothers have made their vamp world an allegory, albeit shyly. Consider the vampires as American capitalists on a global scale, ever complacent and ignorant of their place in the world, helping to drain the planet of its natural resources (in this case, human blood). Their conceit has them living in this moment, not as concerned as they should be about the future as they greedily consume everything they can. And the Subsiders, the poor, spread from the cities to the suburbs as the middle class dwindles away. It’s not an overt commentary, but it’s there, and its presence helps give the violence some purpose.

Still, the last twenty minutes resort to a bloodbath in true horror movie form. These scenes are functional for the most part, and though excessive and gory, they’re not gratuitous in their placement—they always help advance the plot. Put it this way: You won’t find extended scenes of martial arts combat set to techno music here. Occasionally hackneyed (particularly in the final moments), the overall effect of Daybreakers proves Michael Spierig and Peter Spierig have the potential to become great genre filmmakers, following in the footsteps of cult horror masters John Carpenter, George A. Romero, and others. Those are big shoes to fill, but if they continue with the entertaining yet smart style they’ve displayed here, they’ll be well on their way.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review