Reader's Choice

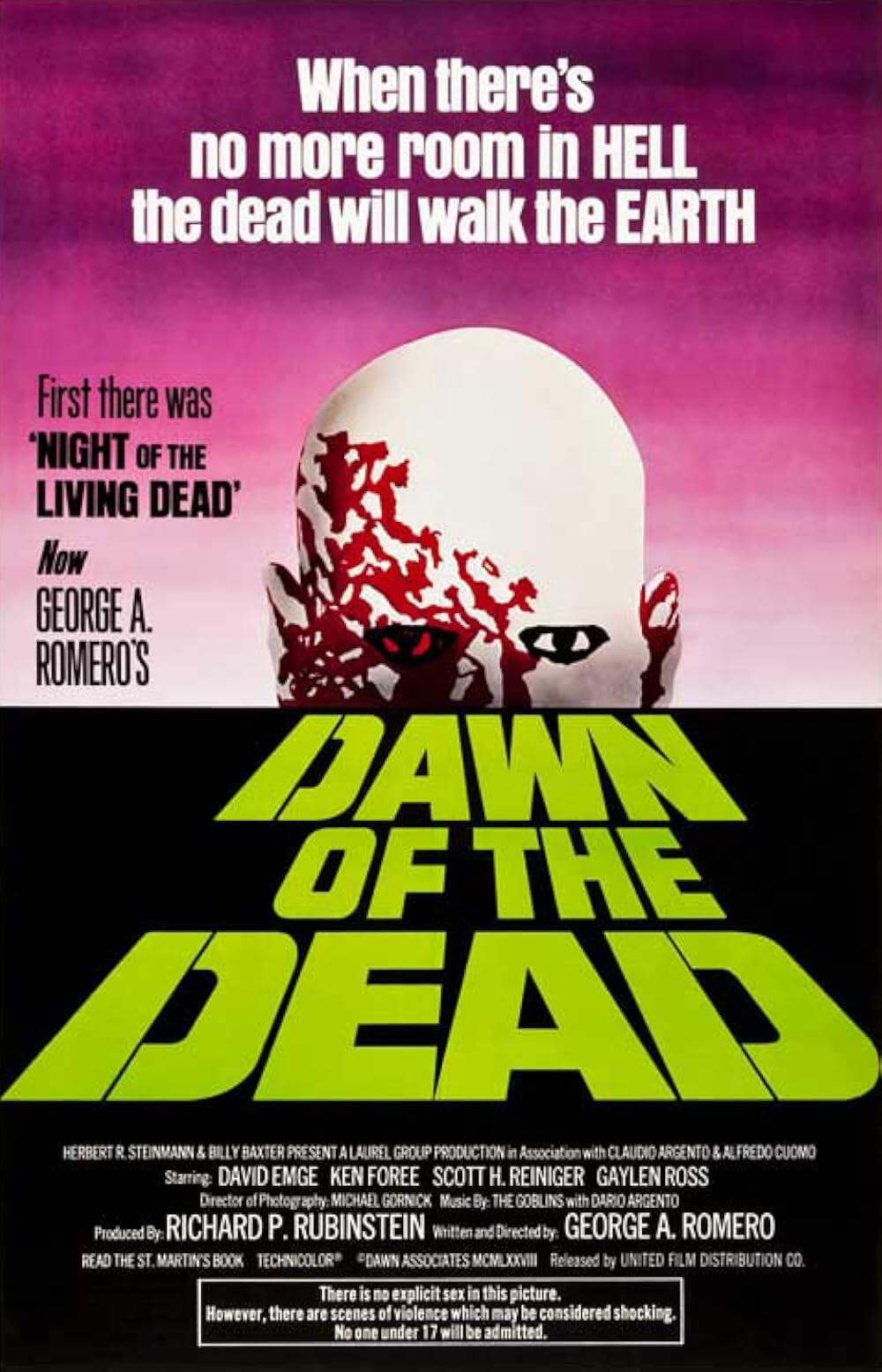

Dawn of the Dead

By Brian Eggert |

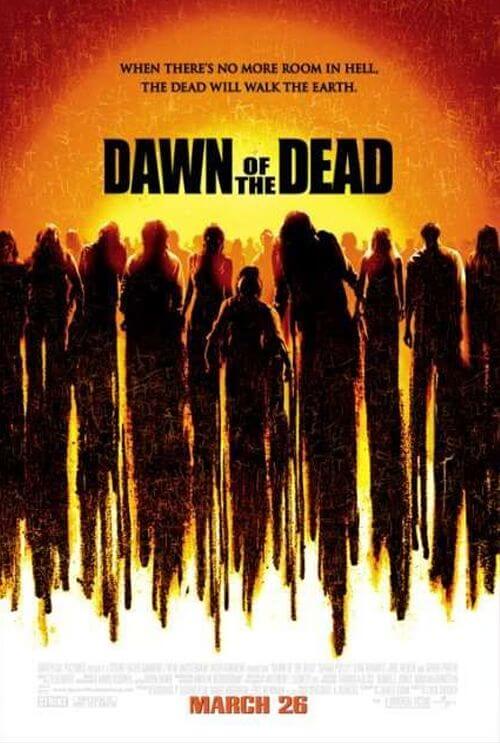

George A. Romero’s critique of materialism in Dawn of the Dead (1978) likened zombies to mindless consumers, but Zack Snyder’s 2004 remake wipes away the original allegory and replaces it with frenetic action. The resulting movie does exactly what one should expect when Hollywood remakes a cult classic for mainstream audiences: The production values, from the recognizable actors to the special FX, appear more expensive. It diminishes, if not altogether eliminates, the social commentary, readying the product for mass consumption. And the visual presentation has been hyper-stylized and accelerated for the shortened attention spans of the twenty-first century. This approach—characteristic of many horror remakes in the 2000s, including a swath of Platinum Dunes titles and Rob Zombie’s Halloween (2007)—might be condemnable from a certain point of view. Except, the outcome in this case proves so damn entertaining, due in large part to the script credited to James Gunn. But it’s also due to the most effective application of Snyder’s stylistic signatures, which manifested in Dawn of the Dead, his debut feature, and have since remained unchanged. Although the remake cannot be credited with improving upon its predecessor, it nonetheless creates an accessible and often viscerally engaging take on Romero’s basic setup.

The differences between Romero’s version and Snyder’s range from the story to the tonality to the films’ aesthetics. In the earlier version, two cops and two civilians hole up in an abandoned shopping mall to hide from the zombie apocalypse. They sweep the mall of any remaining zombies—undead saunter around the mall, mindlessly drifting like shoppers on a weekday afternoon—and make it their home, living off the goods inside and jealously guarding it. But our four heroes slowly deteriorate from their isolation and growing complacency. All at once, their hideout is exposed and trashed by a massive gang of looting bikers, leaving the mall teeming with zombies. Romero’s portrait of humanity’s greed and materialism reveals how these qualities corrupt absolutely. Gunn’s script (doctored by Minority Report scribe Scott Frank) abandons Romero’s observations and, instead, uses the basic survivors-in-a-mall setup as a launchpad for something else entirely. All of the events within the mall take place on their own horrifying terms. More characters allow for additional opportunities for bloodshed. And the seemingly endless string of trials gives the audience little more than a scene or two to catch their breath.

The zombies themselves change too. Romero’s undead were blue-skinned and splattered with bright red blood; they staggered along, almost dawdling to accentuate his anachronistic intent. Taking a cue from Danny Boyle’s zombie reinvention 28 Days Later (2002), Snyder’s zombies sprint at an unrelenting pace, and he decorates them with fleshy, realistic gore. One zombie can run a character down, making every last one of them a frightening threat. Although Snyder’s camerawork is slicker than Boyle’s intentionally frenzied approach, they share an interest in the violent limits of a zombified human body. Whereas a character in Romero’s films could maneuver around one of the undead, or even a small crowd of zombies, just one of Snyder’s zombies behaves as if fuelled by pure hatred adrenaline. The shift reflects an increasingly fast-paced, overstimulated world adjusting to the digital revolution, the post-9/11 news cycle, and the energetic editing of countless music video directors like Snyder, who later turned to movies. The running zombie symbolizes a world that changes so fast we cannot hope to outrun it.

The change signals itself in the tense first scenes that follow the provincial concerns of Ana (Sarah Polley), a Milwaukee nurse who finishes a long shift and returns to her suburban home. There, she settles into American Idol with her husband, Louis (Louis Ferreira), and casually discusses her work schedule before their planned “date night” commences. At the same time, we cannot miss references to a patient who was admitted for a bite and later sent to the ICU, news about violent incidents that “are not isolated,” and an emergency broadcast that sounds on the television. The next morning, Louis wakes to see a neighbor girl standing in their bedroom doorway, her face badly wounded. We recognize her as a zombie; Louis does not. He approaches her, assuming she has been in an accident. Within a few short seconds, the girl hisses and bites a hunk of sinewy flesh out of Louis’ neck. Ana forces her out of the bedroom, locks the door, and then tries to save Louis, who quickly bleeds out and dies. Panicking, Ana tries to call for help, but Louis has already turned. He races after her, screaming with the same guttural sound as the little girl. From there, Ana races into the bathroom, escapes out the window, and runs to the car, only to discover her modest suburban life has turned into chaos.

Gunn’s script never bothers explaining the zombie outbreak—whether made by a virus, contagion, super-Rabies, or what have you—it simply begins, and a few television news clips suggest the outbreak is worldwide. It quickly becomes apparent that Gunn’s strength as a writer is crafting distinct characters with a few simple lines of dialogue, performed by the pitch-perfect cast. Amid the initial chaos, Ana meets a disillusioned police officer Kenneth (Ving Rhames); the natural-born leader and mediator Michael (Jake Weber); and former gang member Andre (Mekhi Phifer), who believes his best chance at redemption is helping to raise a child with the very pregnant Luda (Inna Korobkina). Covered in blood and rattled by the mayhem, they make their way to a nearby mall, where a trio of controlling mall security guards (Michael Kelly, Kevin Zegers, and Michael Barry) exert what little control they have over the situation. The shopping center, the aptly titled Crossroads Mall, provides shelter and resources—making it the perfect safe haven. A second wave of survivors soon arrives, populated by a no-nonsense trucker named Norma (Jayne Eastwood), a rattled young woman (Lindy Booth), and the resident smarmy asshole (Ty Burrell), among other types.

Our sympathies remain with the initial group, namely Ana and Michael’s burgeoning romance, Andre and Luda’s coming child, and Kenneth, who communicates by dry-erase board and binoculars with a gun shop owner, Andy (Bruce Bohne), whose store is a couple hundred yards away, across an ocean of undead. C.J. (Kelly), the security guard who gradually realizes that being a hardass isn’t helping earn the others’ trust, also supplies a sympathetic arc. The others, some mentioned and others not, manage to be distinct without making an impression. With the characters relatively one-note, the decision to leave their consumerist haven is propelled by the plot and not an existential crisis. Isolation and complacency drained the life out of Romero’s survivors. In contrast, Snyder’s cast of characters seems rather content in their mall environment, despite the presence of Bobby McFerrin’s “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” muzak on the speakers. A comic montage set to Richard Cheese’s lounge-style “Down With The Sickness” shows them embracing their inner capitalists, bonding over distanced chess, casual sex, and other vices. But when Andre hides Luda’s zombie bite, leading to several deaths and a zombie baby, the incident becomes a catalyst to leave the mall.

What remains unique about Dawn of the Dead is how Snyder takes the opposite approach as Romero, using fast-paced plotting and action, whereas Romero allowed his film to meander in the slow decline of his characters. As suggested above, Snyder’s style is predictable for anyone versed in his later works, such as 300 (2007) or Sucker Punch (2011), complete with Matthew F. Leonetti’s overexposed colors and the director’s penchant for fast-slow-fast transitions in film speed. Borrowing a trick used by Sam Peckinpah, which he borrowed from Akira Kurosawa, Snyder blends delirious action and slow-motion for dramatic effect. A typical sequence in Dawn of the Dead finds a zombie sprinting at top speeds only to be shot down by a gun firing in slo-mo, the shots fetishizing the discharge from the gun barrel and the empty shells falling to the ground. This sequence repeats itself in the film with decreasing interest. Tyler Bates’ score, too, accentuates these moments, building to a jolt when harsh aural effects shatter the quiet—a sound design that creates jump-scares from a sharp note combined with a sudden cut. Moments of deadly silence are interrupted by the sounds of a zombie banging on a door, a cocked shotgun, or a burst of music turned up to eleven to intensify our sensory experience.

What remains unique about Dawn of the Dead is how Snyder takes the opposite approach as Romero, using fast-paced plotting and action, whereas Romero allowed his film to meander in the slow decline of his characters. As suggested above, Snyder’s style is predictable for anyone versed in his later works, such as 300 (2007) or Sucker Punch (2011), complete with Matthew F. Leonetti’s overexposed colors and the director’s penchant for fast-slow-fast transitions in film speed. Borrowing a trick used by Sam Peckinpah, which he borrowed from Akira Kurosawa, Snyder blends delirious action and slow-motion for dramatic effect. A typical sequence in Dawn of the Dead finds a zombie sprinting at top speeds only to be shot down by a gun firing in slo-mo, the shots fetishizing the discharge from the gun barrel and the empty shells falling to the ground. This sequence repeats itself in the film with decreasing interest. Tyler Bates’ score, too, accentuates these moments, building to a jolt when harsh aural effects shatter the quiet—a sound design that creates jump-scares from a sharp note combined with a sudden cut. Moments of deadly silence are interrupted by the sounds of a zombie banging on a door, a cocked shotgun, or a burst of music turned up to eleven to intensify our sensory experience.

Snyder’s pervasive interest in sensory shocks and style over substance, or style as substance, means his formal touches replace the need to think much. At least the actors give us committed performances. Polley, Weber, and Kelly do incredible things with a few simple lines and scenes. As for the zombie terror, Snyder delivers it with clarity, never skimping on the requisite blood and gore (even more so on the Director’s Cut, which has a few more exploding heads)—some of it practical make-up, some of it CGI. In particular, the last act races, shifting from an ill-advised rescue attempt to a frightening sewer chase, from a breathless escape in reinforced vans to a somber finale at a marina. It’s a delirious series of ghoulish action set pieces, accented by exploding propane tanks and a particularly nasty bit with a chainsaw. The sole misstep: the scattershot scenes that play over the end credits, offering a fragmentary glimpse at how the survivors escape onto Lake Michigan and probably meet their demise. It’s handled with all the subtlety of a bludgeoning to the skull, spoiling any tenderness we may have felt in the last scene before the credits rolled.

Even though the fragmentary credits scenes leave a bad taste, Dawn of the Dead supplies an irresistible burst of energy that makes it worth revisiting. The film also helped solidify, for better or worse, the re-emergence and popularization of zombies in the new millennium. Along with Snyder’s remake, which cost around $26 million and earned over $100 million at the box office, 2004 also brought Edgar Wright’s brilliantly funny Shaun of the Dead. Hollywood got wind that audiences wanted zombies and saturated the marketplace. The next year, Universal Studios brought back Romero to make his first zombie film since 1985’s Day of the Dead, the actionized Land of the Dead (2005). Romero’s return, fuelled by Snyder’s remake, furthered the new demand for zombie material—enough to make fans almost regret its resurgence. Romero made a few more zombie movies of decreasing distinction, AMC’s The Walking Dead and its spin-offs petered out, and zombies became the stuff of YA romances. But no matter how much the genre has been beaten to death in the years since its release, Snyder’s remake is enduringly scary, thrilling, and incurably watchable time after time. It remains his best film.

(Note: This review was suggested by supporters on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review