Darkest Hour

By Brian Eggert |

In 1940, while the United States was hiding behind Neutrality Acts that limited its involvement in future wars, Europe was under siege by Adolf Hitler’s spreading Nazi regime. The Germans had invaded Poland in 1939; that same year, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain met with Hitler to sign over the German borderlands of Czechoslovakia to the Nazis as an appeasement. Denmark, Holland, and Norway soon fell to the Nazis in early 1940. Belgium and France would surrender next. Meanwhile, as the Americans took an isolationist stance that would remain until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the British saw that their leadership was weak. Chamberlain had done little to prevent Hitler’s increasing power, and members of the Conservative Party wanted him replaced. Darkest Hour tells the story of Chamberlain’s successor, Winston Churchill, and his efforts to embolden the fight against the Nazi threat, as well as orchestrate the rescue of Allied troops from Dunkirk (as dramatized by Christopher Nolan earlier this year).

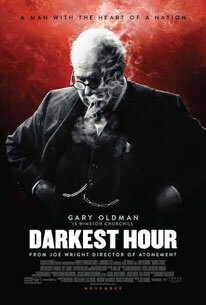

In the same way that Steven Spielberg disguised his character study Lincoln as a political drama, screenwriter Anthony McCarten (The Theory of Everything) uses the first days of Churchill’s office to explore his personality and legacy. Directed by Joe Wright, Darkest Hour presents a familiar brand of Oscar-bait in the filmmaker’s rather ostentatious and overly flashy style—beginning with a splashy performance by Gary Oldman as the rotund Churchill, a portrayal that might be called an embodiment if not for the artificiality behind his physical transformation. Oldman’s appearance—part prosthetics, part digital magic show—is never entirely convincing, though the film’s generally harsh lighting often hides the illusion. Still, there’s always a glimmer of the thin actor beneath the makeup and CGI, and the result, while mostly effective, enters a similar realm as the Uncanny Valley—Oldman’s look is both real and unreal. Speaking with the heavy-jowled inflection of Droopy the dog, he looks and sounds like Churchill. But the trickery is sometimes distracting.

With Chamberlain disliked for the country by King George VI (Ben Mendelsohn), the obvious replacement from the Conservatives is Viscount Halifax (Stephen Dillane), who turns down the job. Churchill is next in line, though his unpredictable personality and unconventional behavior make him a dubious choice (he drinks with his breakfast, downs two bottles of champagne per day, and works into the night). He takes on the post with a degree of uncertainty about his role as Britain’s leader, while his military record remains marked by famous failures. At the same time, grim reports of the German army’s progress require attention, but many in his party (Chamberlain and Halifax) believe peace negotiations should be considered. Stumbling in his approach, Churchill refuses to entertain the mere thought of surrender; he would rather die than subsist under Nazi rule—but his party members aren’t so willing to engage in war or sacrifice, given that their army faces utter annihilation at Dunkirk. Between political maneuvering and military strategy, Churchill must prove his salt.

On the periphery, Lily James appears as Churchill’s typist and secretary, Elizabeth Layton, a thankless role with almost no dimension (the character feels inserted only to break up the monotony of stuffy, overprivileged elder statesmen). More impressive is Kristin Scott Thomas as Churchill’s wife, Clementine; their relationship is full of honesty and playful jibes (she affectionately calls him “pig”), and Thomas plays it wonderfully. Of course, the obvious awards contender remains Oldman, a committed performer giving his all, perhaps too much, in Churchill’s many speeches and curmudgeony scenes. It’s an impressive turn, although the viewer is always aware of the performance happening before us. Nevertheless, Darkest Hour presents a rousing account. The celebrated historical figure served from 1940 to 1945, and then from 1951 to 1955 in a second term before his resignation. And being a grand, larger-than-life leader in a time when inspiring leadership is hard to come by, his symbol is inspiring to be sure—and a reminder that history reveres those who put their country before their personal aspirations.

In keeping with Oldman’s performance, Wright’s visual approach resists subtlety. When a straightforward angle would do, the director finds no reason at all to imbue the material with overhead shots, punctuated editing, and indulgently long takes that rarely advance the story. Instead, they seem like formal showboating. In post-modern efforts like Wright’s music-video-of-a-film Hanna (2011), his rampant style may seem appropriate and infectiously entertaining. But in Anna Karenina (2012) or here, Wright’s particular obsessions with micro-edits around typewriters and meal preparations (present in his work since Atonement from 2007) feel distractingly mannered, whereas the few brief war scenes look like videogame cutscenes put together with expensive CGI. None of these flourishes serve Darkest Hour or represent a metaphoric style, leaving the narrative and form to feel at odds. Alas, with Wright’s constant embellishments and the considerable labor placed on getting Oldman to look like Churchill, the film has a manufactured quality that prevents the viewer from making a full connection. Stirring though the proceedings may sometimes be, Darkest Hour resists absolute immersion so that its audience will notice how much effort went into its making.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review