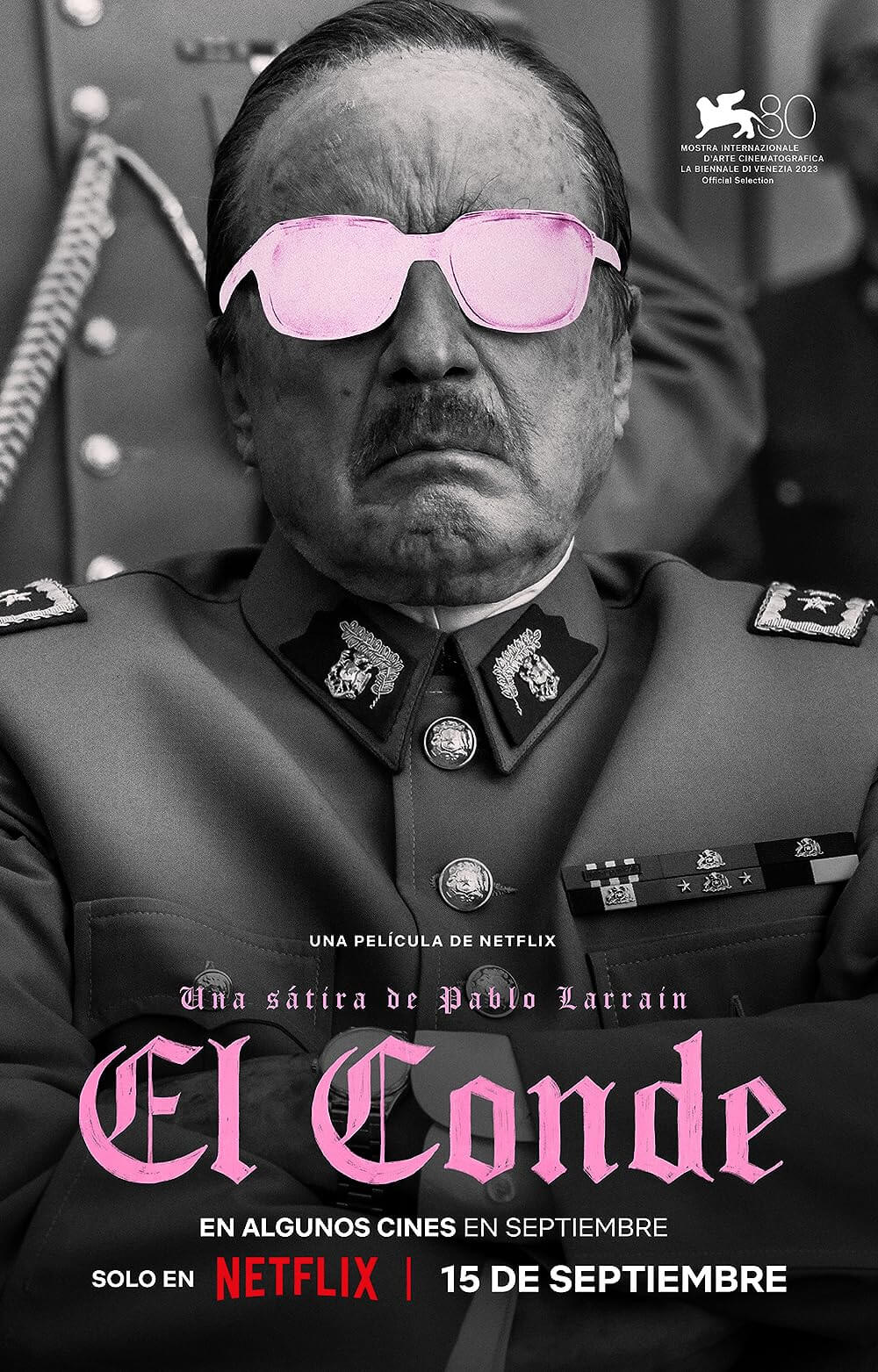

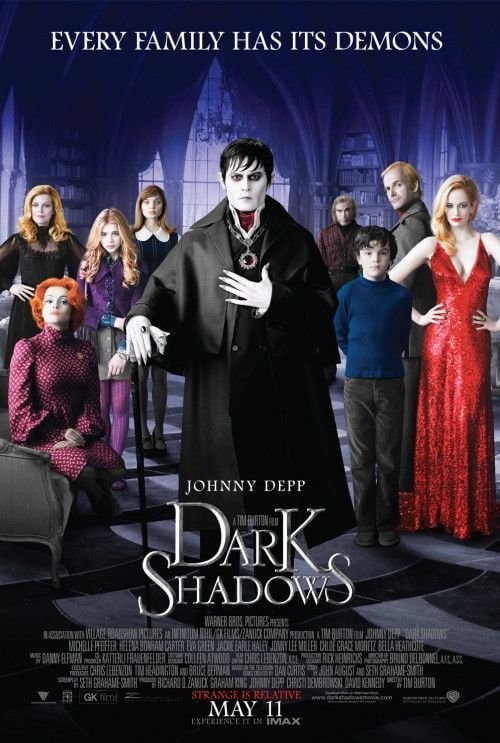

Dark Shadows

By Brian Eggert |

For their eighth collaboration as director and actor, Tim Burton and Johnny Depp pursue another stylish undertaking in gothic-comic territory with Dark Shadows, based on ABC’s daytime drama, which aired from 1966-71 and produced well over 1,200 episodes. Dan Curtis’ gravely serious, supernatural-themed, occult favorite boasted cheesy sets and horror-centric melodramatics, while its central character, vampire Barnabas Collins, played by Jonathan Frid, ached with grand despair and bloodlust from episode to episode. And so, it’s no wonder both Depp and Burton identified with the show in their adolescence, as both have long been drawn to bizarre misfits. Revisiting the material not only appeals to Hollywood’s love affair with bringing back name-brand properties into successful mainstream movies, but it also affords Depp and Burton an opportunity to explore yet another in their long line of black-garbed, pale-skinned, dark-eyed, outsider protagonists with tragic pasts.

It’s not difficult to view Depp and Burton’s latest collaboration as a summation of their earlier work together, but only in the worst ways. Elements from Edward Scissorhands, Ed Wood, Sleepy Hollow, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Corpse Bride, Sweeny Todd, and Alice in Wonderland all have a place here. The film has tragedy and comedy, social and period satire, scary and odd moments, gloomy colors, and bright ones, and given its (rather excellent) soundtrack featuring the likes of Alice Cooper, Donovan, and T-Rex, it’s almost a musical. But as you might imagine, playing mashup with this list of films amounts to little overall cohesion, and that’s the problem with Dark Shadows—a gross mismanaging of the tone. Every moment of potential dramatic significance is usurped by the film’s reliance on lowbrow laughs, and the script by Seth Grahame-Smith, the author of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, never quite balances these counteracting strains of dramatic and comic intent, leaving the viewer distanced and ultimately uninvolved.

Depp plays the exaggeratedly British-accented Barnabas, whose family, we learn in a lengthy prologue, migrated from Liverpool in the 18th century and established a fishing industry in Maine, founding their extravagant estate Collinwood Manor on a high hilltop to look down at their town, Collinsport. But when Angelique (Eva Green), the housemaid he was diddling, finds herself rejected by Barnabas in favor of Barnabas’s love, Josette (Bella Heathcote), she causes Josette to kill herself, curses Barnabas with vampirism, and buries him undead in a coffin for almost two centuries. Construction workers eventually unearth Barnabas and become his first taste of blood in 200 years. After his violent feast (for which he apologies), he finds himself in 1972, where he’s culture-shocked not only by a glowing McDonald’s logo, automobiles, and television, but by the dilapidated state of his family’s former empire.

Living in Collinwood now are matriarchal Elizabeth Collins (Michelle Pfeiffer), her unruly 15-year-old daughter Carolyn (Chloe Grace Moretz), Elizabeth’s klepto brother Roger (Jonny Lee Miller), Roger’s motherless 10-year-old son David (Gully McGrath), and David’s drunkard live-in shrink Dr. Julia Hoffman (Helena Bonham Carter). Barnabas hypnotizes himself a man-servant in the Collinswood caretaker, perpetually smashed Willie (Jackie Earle Haley), and soon finds himself swooning over Victoria, the new governess, who’s a dead ringer for his long lost Josette. The current Collinses have allowed their fishing business to dwindle against the competition, led by none other than Barnabas’ tormentor, the perpetually youthful witch, now called Angie. As Barnabas confronts Angie, he must protect his family, which, in cornball bookend narration, he vows to defend. “Blood is thicker than water,” he declares.

In a modest way, the film employs some effective melodramatic trappings. Victoria’s insane asylum backstory and David’s ghost-seeing troubles amount to small dramatic notes, while Barnabas’ pursuit of love and desire to protect his own from Angie afford woeful scenes. But each attempt at real emotions is defused by irreverent pokes of postmodern humor. Barnabas laments his family’s diminished financial conditions, and then he pauses to regard a troll doll with equal parts fear and amazement. A lava lamp stops him in his tracks. Later, he observes what an ugly woman this Alice Cooper is, only to secure Cooper himself for his “happening” party (an alternative in place of his suggested costume ball) as the rockin’ entertainment. Burton, Grahame-Smith, and Depp never miss an opportunity to wink at the audience about the era’s eccentricities and the resultant culture clashes between 1972 and Barnabas, reducing the potentially weighty material into little more than camp for camp’s sake.

As for the aforementioned soundtrack, the songs themselves would make a splendid playlist of ‘70s hits, but their assignments in the film are shamelessly ironic. The Moody Blues’ “Nights in White Satin” echoes over the title sequence; Barry White chimes in during a raucous love scene; the Carpenters’ “Top of the World” plays over a fixing-up-the-mansion montage. Each song reflects what’s happening onscreen with no end of kitsch and knowing smirks, while the customary Danny Elfman score seems recessive in comparison. What results is a complete absence of the intended growing tension between Barnabas and Angie, which ultimately mounts to an all-out battle laden with special FX and needless spectacle straight out of Death Becomes Her. What the filmmakers have done is translated the material not for fans, but for everyone else. Burton and Depp may have identified with the original show because, as outsiders, they felt they could relate to the morbid characters; however, in their misguided fandom, they’ve made a film as readied for mass consumption as A Very Brady Movie and The Addams Family.

Fortunately, Burton has assembled a wonderful cast, and watching them perform in oftentimes thankless roles remains interesting, if at times painful. Depp commits to his performance, as usual, using flat, baroque vocal inflections outdone only by his excessive use of long-nailed hand gestures straight out of Nosferatu. Green supplies a sexy demoness, her slithery smile and immense, expressive eyes look almost other-worldly under thick, bold eyeshadows and gobs of mascara. Pfeiffer, who gets better with age, remains serious for the most part, as though Burton forgot to tell her he’s making a comedy. Moretz’s misunderstood teen is enjoyable, until she has a silly last-minute supernatural encounter. And the obligatory appearance by Bonham Cater seems present only to supply a villain for a potential sequel.

Produced with Burton’s penchant for spooky, atmospheric sets and vast CGI backdrops, Dark Shadows looks good, and production designer Rick Heinrichs ornaments Collinwood with elaborate wood carvings and lavish, Old Europe embellishments that look appropriately creepy under dust and spider webs. But Burton’s knack for technical and visual flourishes has never been the problem. It’s the film’s uneven tone that leaves something to be desired. Granted, audiences may not be able to revisit the original show today without giggling at the cheapo production values and subpar plotting, but rather than provide a satire of the show, these otherwise talented people could have endeavored to create an equally serious modernization to bring the vampire/witch/werewolf subgenre some much-needed class. Instead, Dark Shadows takes the easy way out by lampooning its source material, simplifying its ‘70s setting through parody, and handling most of the characters like comic relief in an overall treatment that’s beneath everyone involved.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review