Dark Phoenix

By Brian Eggert |

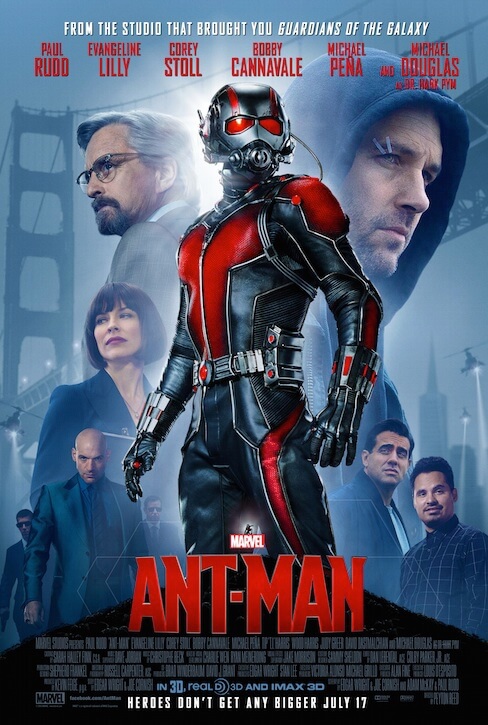

X-Men movies have turned into a late-blooming child who refuses to grow up and move out of their parents’ basement. Most of their siblings have matured, gone to college, taken good jobs, and started families of their own. But aside from the occasional greatness that gives these Marvel Comics superheroes their due, such as Deadpool (2016) and Logan (2017), the series of ten-plus entries has been muddled by an inconsistent timeline, unfaithful characterizations, and underwhelming spinoffs since the 2000 original. Even rousing concepts like X-Men: Days of Future Past (2014) squander their potential by trying to reconcile themselves with the mess that came before. The floundering state of the X-Men franchise has only worsened in the wake of Disney’s acquisition of 20th Century Fox. It seems all of these characters and storylines are bound for a reboot under the Marvel Cinematic Universe in the future, leaving the few X-Men projects lingering under the Fox umbrella to feel utterly pointless.

Such is the case with Dark Phoenix, an X-Men sequel that once again hopes to correct mistakes made in X-Men: The Last Stand (2006), the movie that notoriously killed off several beloved characters and underserviced a major storyline from the comics—namely, “The Dark Phoenix Saga.” For more than a decade, directors Bryan Singer, Matthew Vaughn, and James Mangold have each tried to repair the errors of universe-building and storytelling caused by the third X-Men movie with their own sequels, prequels, and spinoffs. But the franchise has never recovered from the damage left by director Brett Ratner and the screenplay by Zak Penn and Simon Kinberg. Oddly, Kinberg, a longtime writer-producer at Fox, returns with a new script for his first venture into directing with Dark Phoenix, vowing to get right the famous storyline he mishandled the first time around. And while Kinberg had every opportunity to do just that and make a worthy sequel, Dark Phoenix is among the worst of all X-Men movies.

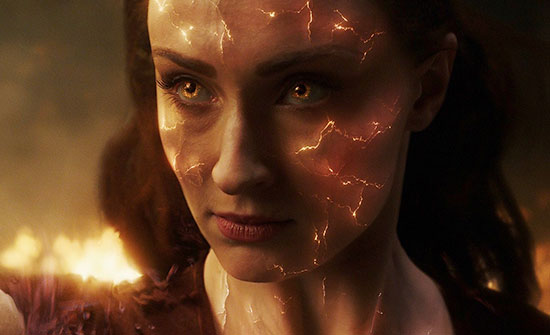

Admittedly, Kinberg’s screen story bears a closer resemblance to the original comic storyline penned by Chris Claremont and John Byrne than The Last Stand, but it still feels like a rushed, shorthand version of the “Saga.” Sophie Turner returns as Jean Grey, the telekinetic mutant who becomes inhabited by the intergalactic Phoenix entity in the early space rescue sequence of the movie. Along with her costar, Tye Sheridan as Cyclops (Jean’s loyal boyfriend), Turner and Sheridan are the best part of Dark Phoenix. She commits to the role’s emotional highs and lows, whereas Sheridan’s character is her rock, as the character should be. Casting has always been this franchise’s strong suit. Who better than Michael Fassbender to evoke the inner rage, anti-authoritarianism, and desire for mutant vengeance of Magneto? Who better than James McAvoy to capture the intelligence, understanding, and hope of Professor X? While the casting of Dark Phoenix is often inspired, Kinberg’s continued mistreatment of the characters left me with the persistent feeling that I didn’t recognize the heroes whose comic books I read as a boy.

Perhaps this is a good time to bring up Jennifer Lawrence. Given her star power, the franchise has made the curious choice to position a relatively minor character, Raven (aka Mystique), into the leader of the X-Men in the field (a bit like making Batman the sidekick to Harley Quinn). After Jean is imbued with untold spatial powers by the Phoenix entity that amplifies her abilities and emotions, Raven begins to ask questions about Jean’s former “broken” emotional state, and how Professor X “helped” her as a child. Raven also begins to question Professor X’s motivations and, in a streak of feminism, wonders why they’re called “X-Men” and not “X-Women,” since the most powerful mutants on the team are female (hence the absence of X-Men in the title). Later in the movie, Raven becomes a martyr, and the remaining heroes use her as a shining beacon, as if to ask, “What would Raven do?” The sheer amount of dialogue and story that revolves around this otherwise supplementary character feels incongruous for any fan of the comic, unnaturally contorting the material to appease Lawrence’s celebrity—a thread sewn into both Days of Future Past and X-Men: Apocalypse (2016). It distracts from the primary thrust of the narrative: Jean.

Perhaps this is a good time to bring up Jennifer Lawrence. Given her star power, the franchise has made the curious choice to position a relatively minor character, Raven (aka Mystique), into the leader of the X-Men in the field (a bit like making Batman the sidekick to Harley Quinn). After Jean is imbued with untold spatial powers by the Phoenix entity that amplifies her abilities and emotions, Raven begins to ask questions about Jean’s former “broken” emotional state, and how Professor X “helped” her as a child. Raven also begins to question Professor X’s motivations and, in a streak of feminism, wonders why they’re called “X-Men” and not “X-Women,” since the most powerful mutants on the team are female (hence the absence of X-Men in the title). Later in the movie, Raven becomes a martyr, and the remaining heroes use her as a shining beacon, as if to ask, “What would Raven do?” The sheer amount of dialogue and story that revolves around this otherwise supplementary character feels incongruous for any fan of the comic, unnaturally contorting the material to appease Lawrence’s celebrity—a thread sewn into both Days of Future Past and X-Men: Apocalypse (2016). It distracts from the primary thrust of the narrative: Jean.

As Jean’s emotions flare, inadvertently hurting those around her, the X-Men team—the blue-furred Beast (Nicholas Hoult), the weather-controlling Storm (Alexandra Shipp), the teleporting Nightcrawler (Kodi Smit-McPhee), and the speedy Quicksilver (Evan Peters)—try to bring her home. Before long, Magneto joins the fight to stop Jean too. Adding plot atop plot, Kinberg decides to throw an alien invasion into this already loaded concoction, and it’s a needless distraction similar to the “mutant cure” he devised for The Last Stand. A shape-shifting alien race whose planet was obliterated by the Phoenix, the leader of which takes the form of Jessica Chastain, wants to obtain the entity inside of Jean and colonize Earth for themselves. Chastain’s character attempts to manipulate Jean and convince her that she’s weak because of her out-of-control emotions, leading to Jean’s revelation that “My emotions make me strong!”—a similar epiphany had in this year’s Captain Marvel.

Lackluster CGI battles between Jean and her fellow X-Men, and between the superpowered mutants and aliens, ensue, revealing Kinberg’s weakness as a director. Somehow, none of the set-pieces in this reportedly $200 million production incite awe or exhilaration—suggesting that most of the price tag went to the impressive cast’s salaries. Although it’s fun to watch Nightcrawler pop into a scene and deliver a punch, then disappear, it’s less interesting to watch Magneto raise his hands and, without visible beams or waves, see metallic objects react. At times, it’s like watching adults play superhero the same way young children might; the difference is Fassbender’s strained physical commitment to these moments. Additionally, X-Men movies, despite a fount of mutant characters to pick from in the comics, always manage to add one or two with laughable mutant powers into the mix. The first X-Men movie featured a character named Toad with an extended tongue; X-Men: First Class (2011) had a woman with dragonfly wings; in Dark Phoenix, there’s an unnamed Magneto goon played by stuntman Andrew Stehlin who uses his long braided hair like whips—and it’s unintentionally hilarious.

Elsewhere, issues of the franchise’s out-of-joint timeline raise questions. Note how the story takes place in 1992. A conservative estimate suggests Magneto, a Holocaust survivor, should be in his sixties, but Fassbender looks about 42 in the role and without a gray hair on his head. Likewise, Professor X was twentysomething in 1962, when First Class took place, making the wheelchair-bound character at minimum 50 in Dark Phoenix, but again, the actor playing him looks youthful (and you would think that having to save the world over and over would add years to a person’s face). Other traits of X-Men movies remind us how the series has faltered creatively: corny bookend narration, a preoccupation with vehicular disasters, and underdeveloped supporting characters. It’s all very dull, and it all ends in a conspicuously similar way to the penultimate scene in The Dark Knight Rises (2012).

Elsewhere, issues of the franchise’s out-of-joint timeline raise questions. Note how the story takes place in 1992. A conservative estimate suggests Magneto, a Holocaust survivor, should be in his sixties, but Fassbender looks about 42 in the role and without a gray hair on his head. Likewise, Professor X was twentysomething in 1962, when First Class took place, making the wheelchair-bound character at minimum 50 in Dark Phoenix, but again, the actor playing him looks youthful (and you would think that having to save the world over and over would add years to a person’s face). Other traits of X-Men movies remind us how the series has faltered creatively: corny bookend narration, a preoccupation with vehicular disasters, and underdeveloped supporting characters. It’s all very dull, and it all ends in a conspicuously similar way to the penultimate scene in The Dark Knight Rises (2012).

It’s not that Dark Phoenix is a complete disaster—it’s that the franchise hasn’t changed much in the last 20 years, while the rest of the superhero genre has continued to grow and evolve. The movie is certainly preferable to The Last Stand, but that’s not saying much. Kinberg delivers a straightforward entry in the X-Men series that should have done justice to the beloved storyline and soared above the others. Instead, he does what X-Men movies usually do, which is muddle the storytelling and characters while presenting a watchable blockbuster for those only mildly invested in the material. Though other comic franchises from Fantastic Four to The Punisher have learned the hard way that audiences care about the integrity of the intellectual property—and the MCU continues to take strides in this department—the X-Men movies have only a few examples that demonstrate their awareness of this (again, see Deadpool or Logan). How ironic that movies about the next stage in human evolution remain so committed to outmoded superhero moviemaking.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review