Dark Harvest

By Brian Eggert |

Dark Harvest is a new Halloween classic—a spooky tale about folklore, tradition, and the urgent need to revolt against blind conformity. A marriage of Shirley Jackson’s short story “The Lottery” and Stan Winston’s Pumpkinhead (1988), the film takes place in an American farming community in the early 1960s, during the annual harvest celebration. The small town’s mythology vaguely resembles the Gaelic Irish festival called Samhain, when the doors to the Otherworld were most open to spirits, and people sought to honor them with food, drink, and costumes. Despite the Midwestern setting, the customs in Dark Harvest prove far removed from Halloween, an offshoot of Samhain that in America finds children dressing up in branded department store costumes and knocking on doors, asking for candy. Even so, every year, the local boys wear masks; they also carry pitchforks, baseball bats, and other melee weapons in search of a fire-breathing, pumpkin-headed monster named Sawtooth Jack. Whether or not the creature reaches the town church, after emerging from the cornfield and slaying anyone in his path, determines if next year’s harvest will bring “peace, prosperity, and prize crops,” as the resident mayor hopes.

Based on the 2006 novel by Norman Partridge, the film inhabits a self-contained world where the farm field horizon reaches so far into the distance that nothing might exist beyond it. There, the people are primarily white and Christian, and the one Black family remains segregated. The local law enforcement, Officer Ricks (Luke Kirby), holds court in the high-school gym, where he spouts off like a drill sergeant to bloodthirsty boys about the necessity of killing Sawtooth Jack. This so-called Midnight Run is a difficult pitch, requiring each boy to fast for three days while locked in their room, fuelling their hunger and desperation to win. Officer Ricks also sells them on the rewards—a flashy new Corvette, a house on the nice side of town, and a check for $25,000, which, in 1963, could change the winner’s life. The parents appear enthusiastic about the prospects of their sons winning the annual competition, but there’s also a sense of unease, perhaps from the danger inherent to the hunt. Perhaps something else. Writer Michael Gilio adapts the material into a story worthy of The Twilight Zone, with an earth-shattering twist and a fiery social consciousness.

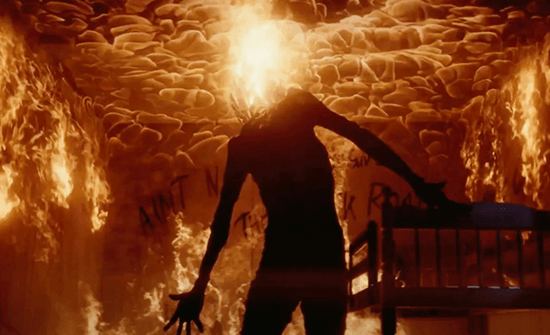

The film opens with a disorienting sequence that finds the jocular teenager Jim (Britain Dalton) catching up with the lanky autumnal terror near the local church and then beating it to death. What follows is a grisly scene even more terrifying than the monster itself—a convincing-looking blend of practical effects and CGI. The boys who are after Sawtooth Jack plunge their hands inside him to pull out his innards—hunks of candy and stringy licorice whips slathered in the beast’s dark blood—which they consume with the voracious glee of rabid dogs. Afterward, Jim receives the promised reward; he drives toward the horizon in his brand-new car to explore the world, announcing, “Ain’t no stop signs on the black road.” Jim leaves behind his brother Richie (Casey Likes), who is tired of living in the middle of nowhere and, a year later, vows to escape by repeating his brother’s success when Sawtooth Jack inevitably returns. He does this against the protests of his stern father, Dan, and loving but shattered mother, Donna, played by Jeremy Davies and the great Elizabeth Reaser, who feel slightly underused.

The teens in Dark Harvest occupy a social dynamic worthy of S.E. Hinton, with sportos and greasers beating their chests at one another. When the next Halloween season approaches, Richie prepares to compete, but Riley (Austin Autry), an Alpha douchebag in a letter jacket, intends to win, even if it means beating Richie to a pulp. According to the rules, Richie cannot compete because his brother won. But he’s a rebel—part of a three-member gang called the Bandits—and he wants out of town. So does Kelly (E’myri Crutchfield), a teen girl of color who recently moved to town and finds that she’s not welcome to participate because of her gender and skin color. She’s a rebel, too, with a backstory that includes some mild pyromania and fearlessness in the face of bigotry. Crutchfield is especially terrific in her role, offering a charismatic character who feels comfortable in her skin despite the intolerance surrounding her. Together, they resolve to find Sawtooth Jack, win the competition, and leave their small-town life behind. But once the Midnight Run starts, they face not only the monster from the cornfield but a starved, desperate band of young zealots bent on fulfilling their duty and earning the prize.

The teens in Dark Harvest occupy a social dynamic worthy of S.E. Hinton, with sportos and greasers beating their chests at one another. When the next Halloween season approaches, Richie prepares to compete, but Riley (Austin Autry), an Alpha douchebag in a letter jacket, intends to win, even if it means beating Richie to a pulp. According to the rules, Richie cannot compete because his brother won. But he’s a rebel—part of a three-member gang called the Bandits—and he wants out of town. So does Kelly (E’myri Crutchfield), a teen girl of color who recently moved to town and finds that she’s not welcome to participate because of her gender and skin color. She’s a rebel, too, with a backstory that includes some mild pyromania and fearlessness in the face of bigotry. Crutchfield is especially terrific in her role, offering a charismatic character who feels comfortable in her skin despite the intolerance surrounding her. Together, they resolve to find Sawtooth Jack, win the competition, and leave their small-town life behind. But once the Midnight Run starts, they face not only the monster from the cornfield but a starved, desperate band of young zealots bent on fulfilling their duty and earning the prize.

After directing his first feature, Kwik Stop (2001), Gilio has remained a writer with a couple of original scripts that made the annual Black List of the best still-unproduced screenplays. His writing on Dark Harvest not only has a firm grip on the material’s creepy small-town fervor but also the characters who inhabit this deeply symbolic scenario. In Gilio’s hands, the story’s allegorical power never feels overstated, and the mythology is just vague enough to remain compelling, mysterious, and haunting. The frantic moment-to-moment pacing prevents the material’s symbolism from taking over. Expertly directed by David Slade, a genre aficionado whose credits include the choose-your-own-adventure Black Mirror movie Bandersnatch (2018), the film embraces its other-worldliness and avoids neutralizing that quality for the audience’s sake. Take the surreal sequence when the Midnight Run descends into a murderous rampage, with starving teen boys so desperate to win that they turn on each other and the local butcher (Mark Boone Junior) for something to eat. It’s a mind-fraying sequence that resets the rules of everything that came before.

Slade has tackled similar material with 30 Days of Night (2007), another twisted tale about an isolated small town and a supernatural threat. In that film, a gang of vampires descend on an Alaskan hamlet where the sun won’t reappear for a month, leaving everyone at the bloodsuckers’ mercy. There’s a similar approach to the frenzied scenes of the Midnight Run in Dark Harvest, with Slade orchestrating the vast scope and horror with expert clarity and camera-wobbling chaos. Slade and Larry Smith—the British cinematographer who shot Eyes Wide Shut (1999) for Stanley Kubrick and regularly collaborates with John Michael McDonagh (Calvary, 2014) and Nicolas Winding Refn (Bronson, 2008)—create images that convey the insanity of what unfolds but with a sense of iconography. Framing the thin, lumbering figure of Sawtooth Jack against blazing fire or capturing a blood geyser in slow motion, the filmmakers imbue the film with a sense of sublime visuality. Not since Trick ’r Treat (2007) has a film so immediately earned its place in the pantheon of seasonal essentials.

What elevates Dark Harvest beyond its monster movie package is Richie’s critical desire to question these traditions and start over with something new. At the heart of this small town is a yearly tradition whose origins remain mysterious and unquestioned, and whose source of power goes unexplored, making it even scarier and more fascinating. And like a terrible entity from an H.P. Lovecraft story, the creature’s monumental presence commands mindless followers. Tapping into the chilling nature of the story, Slade doesn’t pull punches to deliver a Hollywood ending. And yet, there’s a social critique about the decidedly white patriarchal traditions perpetuating themselves because no one ever asks, “Why are we doing this?” This links the film to contemporary discussions in politics, entertainment, and social spheres. Unlike many recent films with themes of social justice, Dark Harvest presents itself without needing a Rod Serling figure to explain its meaning. But by the final frames and into the end credits, the film’s parable quality turns the experience into a passionate call for revolution—to burn down backward establishments preserved out of unthinking allegiance to tradition. It’s a fable that reminds us what makes horror such a vital genre, not just for scares but also for symbols that can be used to examine our world.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review