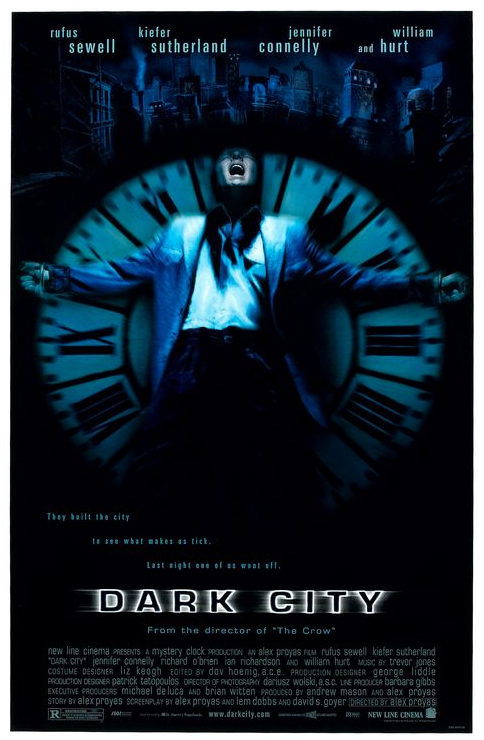

Dark City

By Brian Eggert |

With each film, Alex Proyas comes painfully close to greatness. But something always holds him back from becoming a great filmmaker. Somewhere along the way, whether from studio influence or his own judgment, Proyas resolves to needlessly feed commercial desires. Rather than find an equilibrium between crowd-pleasing entertainment and thought-provoking ideas, his output wobbles and ultimately tips into the realm of conceptually inventive but overtly commercial fare. Proyas’ 1998 effort Dark City represents the very best of his career, a film that one cannot help but admire; but like the director’s other work, a solid setup gives way to a few too many clichés, most notably a silly fight-to-the-death climax. And yet, Proyas’ mark on the film is unquestionable, his visual initiative awesome, and his execution more than compensatory for whatever faults the story may have.

Inspired by classic science fiction, Proyas allows for an undeniable comparison between Dark City and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, and not only in terms of their visual similarities. Both films search for the essence of humanity in an artificial world. Inhuman forces construct a façade, and in both cases, the veneer crumbles because of the human need to question their existence. Whereas Lang’s film offers a utopia for humans that’s ultimately revealed to be false, Proyas’ tale treats its human subjects like rats within a constructed maze. The false city in the film exists in perpetual night, its citizens dejected and wandering, a general sense of malaise coating everything and everyone. The setting is uncertain in time though reminiscent of a 1950s film noir, as there’s a combination of vintage décor and modern conveniences. We see fedoras, automats, old and new cars, and newfangled technologies. The façade is more like a real city, filled with crime, depression, and confusion, but also hints of exposed artificiality.

The Strangers, an alien race in charge of this Dark City, change the simulated world every night when the clock strikes twelve. All at once, everything shuts down. Automobiles roll to a stop. People drop to the ground into a deep sleep. The Strangers, carrying names like Mr. Hand and Mr. Sleep, emerge to alter the geography of the crowded cityscape. Skyscrapers reduce to small office buildings. Dank apartments become luxurious homes. But they also amend the memories of its citizens, using the smarts of human scientist Dr. Schreber (Kiefer Sutherland) to implement a human experiment. With new memories injected into their foreheads, people’s positions change. Clerks become cops. Rich become poor. It’s all in an attempt to determine whether or not human nature is simply a summation of memories and social positions, or something deeper and more profound. The Strangers have a strong desire to know, as their own race is dying and they require human bodies to use as hosts.

When the protagonist (Rufus Sewell) wakes up during the memory implant process, he doesn’t remember who he is. His name is evidently John Murdoch, but he doesn’t recollect that name or his supposed life at all. After some checking, he learns that he was once a happy husband, but after his wife Emma (Jennifer Connelly) had an affair, he became a ruthless killer of prostitutes. In his amnesiac state, Murdock has no intention of killing anyone, so his discovery is all the more shocking. Indeed, this is no utopia. Pursuing Murdock is Detective Bumstead (William Hurt), a ponderous cop that senses something curious about Murdock and the entire world. What’s more, The Strangers, tall and pale and garbed in black, realize Murdock has resisted memory implantation and seek to stop him.

The Strangers are shocked when they realize that Murdock has the ability to “tune,” a form of telekinesis possessed only by them. Tuning allows them to move the Dark City and change its nature; for example, he can move objects or shape a door where there wasn’t one before. That Murdock can do this suggests he is very dangerous, and that perhaps Dr. Schreber has tampered with Murdock’s memory implants. The chase progresses as Murdock seeks to answer the question “Who am I?” Meanwhile, his tuning powers grow stronger and his curiosity greater, sadly building up to a hokey face-to-face between Murdock and the alien leader, who proceed to spar using their telekinetic powers. Though the “final battle” regression of the plot squanders many of the ideas that came before it, the bulk of the film plays out with an aptitude for the themes at the root of all great science fiction.

The Strangers are shocked when they realize that Murdock has the ability to “tune,” a form of telekinesis possessed only by them. Tuning allows them to move the Dark City and change its nature; for example, he can move objects or shape a door where there wasn’t one before. That Murdock can do this suggests he is very dangerous, and that perhaps Dr. Schreber has tampered with Murdock’s memory implants. The chase progresses as Murdock seeks to answer the question “Who am I?” Meanwhile, his tuning powers grow stronger and his curiosity greater, sadly building up to a hokey face-to-face between Murdock and the alien leader, who proceed to spar using their telekinetic powers. Though the “final battle” regression of the plot squanders many of the ideas that came before it, the bulk of the film plays out with an aptitude for the themes at the root of all great science fiction.

Dark City’s visual ingenuity demands appreciation. Proyas has designed a palette completely rendered in shades of dark—bleak blacks and browns, heavy greens and blues—contrasted by the bright blue sky and sunshine in the characters’ ersatz memories. Even though his visuals are appropriately dark, the film retains impressive clarity, allowing the audience to lose themselves in the detailed set design and the edifice of the counterfeit city. His use of special FX also appears subtle yet expertly ingrained into the plot, since the alien technology answers for the strange computerized appearance of moving buildings and telekinetic powers. It’s all set to editor Dov Hoenig’s unrelentingly swift rhythm and sustained by Trevor Jones’ gripping suspense score.

Though at times visionary, Proyas has a history of creative disputes and troubled productions, and yet his films prove to be visually and intellectually stimulating nonetheless. When filming his 1994 film The Crow, his leading man Brandon Lee died in an unfortunate on-set accident; Proyas creatively filled the holes with stuntmen and clever camerawork. His disputes with New Line Cinema on Dark City would eventually lead to a much-demanded Director’s Cut. And the director has been nothing but vocal about Fox’s dogmatic creative control in 2004 on his Will Smith sci-fi actioner I, Robot. Only recently, with 2009’s Knowing, has Proyas been allowed complete creative control. Despite his constant battle to get his films made the way he envisions, his directorial signatures are unmistakable from picture to picture.

Released in 2008, the long-awaited Director’s Cut of Dark City became available to consumers on home video, and it fixed some of the problems in the studio-minded Theatrical Cut, but ultimately created more problems than it was worth. Jennifer Connelly’s voice is used when Emma sings “Sway” and “The Night Has a Thousand Eyes”, as opposed to Anita Kelsey’s original voice dub. Schreber’s over-explanatory opening narration was cut for Proyas’ version, which originally contained spoilers about The Strangers being aliens. About ten minutes of scenes were added and the tempo was dramatically slowed for severity’s sake, but these alterations don’t add much depth to the story. Altogether lost in the Director’s Cut is the frenetic pace of Hoenig’s editing and the dominant use of Jones’ chase theme, two of the most appealing features in the original. Though it may not be the director’s preferred version, the 1998 cut remains superior, if only for its pacing.

Using an array of entrenched science fiction tropes, Dark City follows a scenario molded from many of the genre’s modern films in presenting big ideas and ultimately losing them for the sake of entertainment value. There’s nothing wrong with trying to entertain your audience, but Proyas spends the better part of his film’s runtime making us think, yet still, he resolves his conflicts with an overblown, computer-generated battle in the finale. Granted, while the climax may feel unnatural next to the existentialist journey that occupies the remainder of the film, what lasts is the bravado visuals and dynamic imagery evident in every frame. This is an exceptionally stylish-looking production driving a story with grand aspirations, and though flawed, like the majority of Proyas’ work, it achieves most of what it sets out to do.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review