Reader's Choice

Damsel

By Brian Eggert |

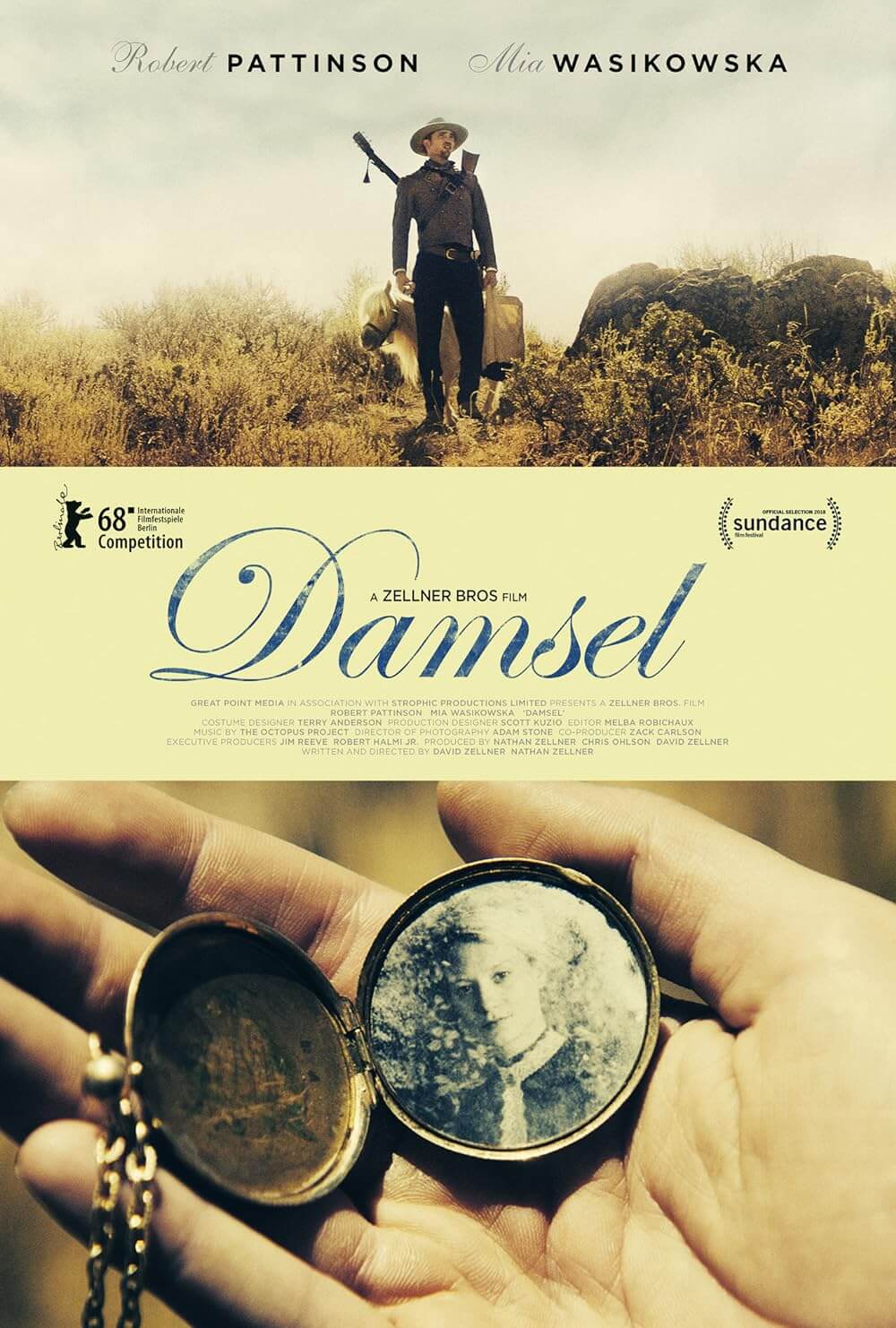

Damsel, written and directed by the Zellner brothers, might answer the question of why no one smiles in Wild West photos. Experts argue that early cameras required longer exposure times, so photographers demanded stillness and a straight face to make a clearer picture. The Zellners’ film suggests there wasn’t much to smile about. Late in the proceedings, a rough-looking bunch of grotesques poses for a photo in a saloon. They appear filthy, warped, and defeated by their hard lives. Their appearance reminds us of the brilliant first scene at a stagecoach stop in the middle of a desolate landscape, with an Old Preacher (Robert Forster) headed back East, and a Pioneer (David Zellner) going to the so-called Land of Milk and Honey for a fresh start. The Pioneer asks the Old Preacher why he’s leaving the West. The downtrodden holy man responds by classifying the West as “shitty in new and fascinating ways.” Then, all at once, the Old Preacher gives the Pioneer his Bible, its pages torn out to make fires and wipe his ass, and begins to strip down to his long johns. He tosses his clothes to the Pioneer and heads out into the wasteland, crazed, ranting, and welcoming his end. By the time the film is over, no character in Damsel could be blamed for doing the same.

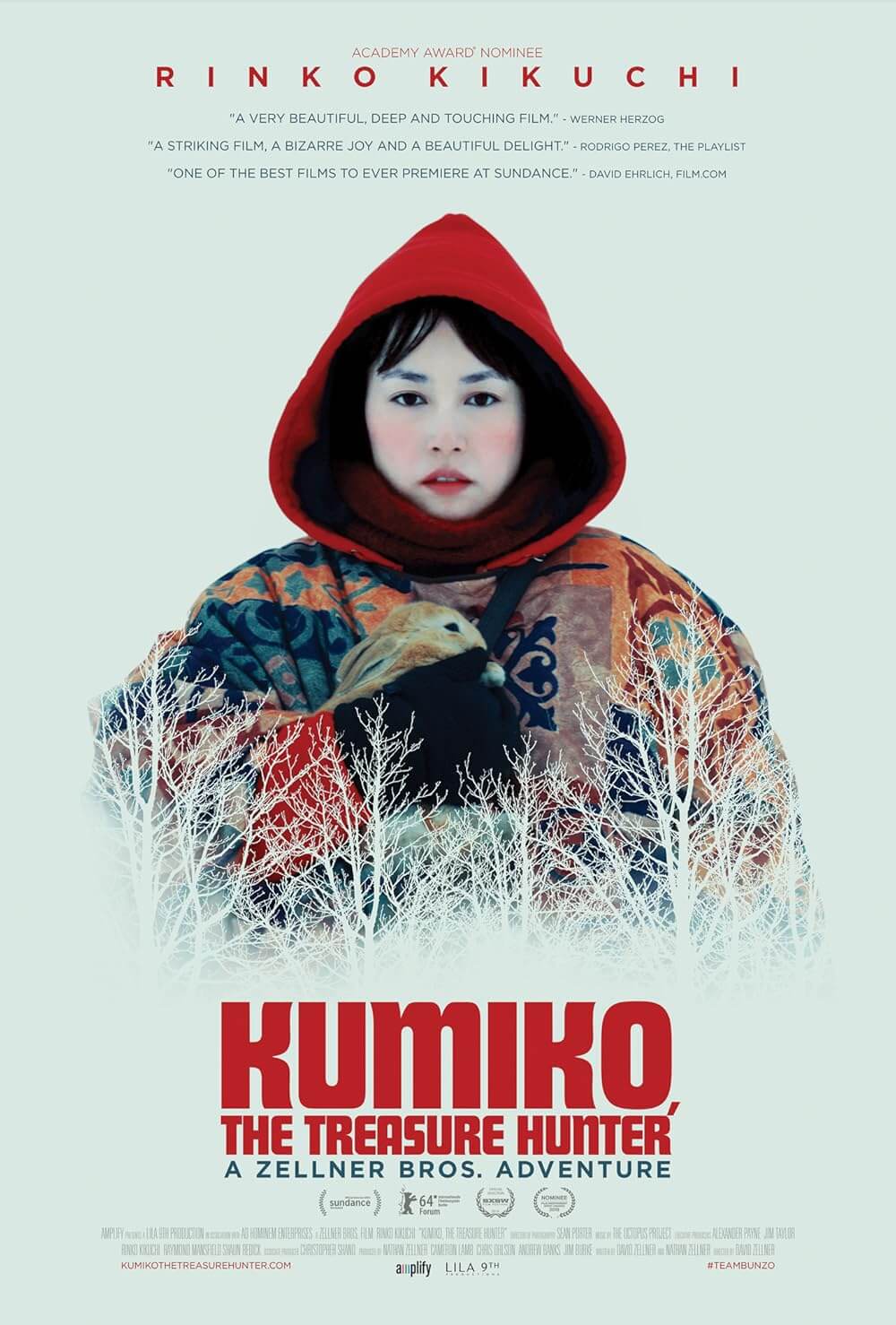

Demystifying the West with the blackest and weirdest humor, the Zellners’ post-revisionist filmmaking comments on the Western, exploring form and gender roles through a series of absurdist oppositions. With Damsel, they match the tone of another pair of genre refashioners, Joel and Ethan Coen, by seeing a Western through an alternate lens. Part pastiche, part ironic takedown of Western masculine stereotypes, the film engages the viewer in a traditional genre fantasy of a male hero saving a female damsel in distress. But it doesn’t take long for Damsel to reveal the Zellners’ project of actively working against Western traditions in hilarious and disturbing ways. While the Coens are legendary for rethinking film noir with Blood Simple (1984), The Big Lebowski (1998), and The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001), the Zellners are known for paying homage to the Coens. For instance, they turned the urban legend about a Japanese woman who died searching for the fictional buried cash from the Coens’ Fargo (1996) into their breakthrough, Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter (2014). The Zellners carry on the Coens’ approach—and that of filmmakers from Quentin Tarantino to the Wachowskis—of allusionism and critique through a distinctly personal perspective.

Damsel begins like many other Westerns—with a man on a journey and a woman in peril. From his first appearance, rowing to a foggy shore and accompanied by a miniature pony named Butterscotch, Samuel Alabaster (Robert Pattinson) isn’t what we expect of a Western hero. Named after a soft rock, he’s what you might call a dandy, evidenced by his crisp new clothes and delicate mannerisms. When he enters a saloon and begrudgingly orders a whisky because there’s no pilsner, a drunk mocks him for barely sipping the drink. “You a pussy?” asks the drunk. Samuel admits, “You could say my stomach is.” Armed with a revolver and a guitar, he’s no gunslinger, no Johnny Guitar. Instead, he’s a man determined to rescue and finally marry his fiancée, Penelope (Mia Wasikowska), who has been kidnapped—at least, that’s what he tells the Pioneer, who is now calling himself Parson Henry (David Zellner), a local boozer hired to officiate Samuel and Penelope’s wedding. “She’s the most precious thing in the whole world,” Samuel declares, showing Henry his locket. “She’s like a flower.” He even shares with Henry the song he wrote for Penelope called “Honeybun,” with lyrics (written by Pattinson) like, “I love you, can’t you see? I want you just for me.”

Pattinson’s performance shows the serious actor from Good Time (2017) and High Life (2019) also has an underused comedic side. Watch the scene where two men measure manliness by comparing the size of their Adam’s apples—not their guns or a pissing contest. Their approach deconstructs the Western by resetting its male perspective, presenting Samuel as a riotous alternative to the usual hero archetype: instead of a gruff beard, he maintains a cleanly trimmed goatee; he’s a lousy shot; he crabwalks on the ground to avoid scuffing his fine clothes; and when he attempts to remove his locket in a single-pull gesture as a gift for Penelope, he cannot manage it. And then there’s the sight of Butterscotch, a wedding present for Penelope, a delicate and fancy creature that has no place in the Wild West, just like Samuel. What’s more, he’s not even the film’s hero; Samuel’s mission isn’t exactly what he described to Henry. The Zellners reveal that his noble rescue of Penelope from her “pure evil” kidnappers are the actions of an obsessed stalker. Samuel has pursued his object of affection with fanatical blindness, justifying his behavior because “I’m just a man—a man who believes in pure love!”

Pattinson’s performance shows the serious actor from Good Time (2017) and High Life (2019) also has an underused comedic side. Watch the scene where two men measure manliness by comparing the size of their Adam’s apples—not their guns or a pissing contest. Their approach deconstructs the Western by resetting its male perspective, presenting Samuel as a riotous alternative to the usual hero archetype: instead of a gruff beard, he maintains a cleanly trimmed goatee; he’s a lousy shot; he crabwalks on the ground to avoid scuffing his fine clothes; and when he attempts to remove his locket in a single-pull gesture as a gift for Penelope, he cannot manage it. And then there’s the sight of Butterscotch, a wedding present for Penelope, a delicate and fancy creature that has no place in the Wild West, just like Samuel. What’s more, he’s not even the film’s hero; Samuel’s mission isn’t exactly what he described to Henry. The Zellners reveal that his noble rescue of Penelope from her “pure evil” kidnappers are the actions of an obsessed stalker. Samuel has pursued his object of affection with fanatical blindness, justifying his behavior because “I’m just a man—a man who believes in pure love!”

Just after the midway point, Samuel and Henry attack and kill Penelope’s so-called kidnapper. But in that exact moment, Penelope emerges from her quiet cottage in the wilderness and reframes the situation: she and her beau, Anton Cornell, have been married for some time. Penelope says that she was “the happiest I’ve ever been in my whole life” with Anton, but Samuel has ruined everything. Worse, he chooses this moment to get down on one knee and propose. “I could never love you,” announces Penelope. “Am I finally getting through to you?” It’s a line that suggests Samuel’s one-sided pursuit of Penelope has gone on for a disturbing amount of time, years even. At this moment, Damsel becomes another film altogether, placing Penelope at the center of a cruel comedy in which every man she encounters assumes she needs rescuing and marrying. According to the usual Western schema, each man attempts to fulfill his role, that of a heroic savior and conqueror of women. But the self-reliant Penelope doesn’t need to be saved.

Penelope’s experiences with these men are endless, exhausting, and tragic—but also seriously funny. Each of them has terrible timing and misguided, unrequited intentions, to the degree that the viewer can only laugh at the procession of ill-advised come-ons. Not long after her husband’s death, not to mention Samuel’s suicide after realizing Penelope will never have him, Henry offers himself to Penelope. “You’re a beaut,” he says, as if that’ll convince her. Then comes Anton’s trapper brother Rufus (Nathan Zellner), who claims, “It’s customary for [a widow] to marry the brother of the deceased.” But Penelope is rescued from Rufus’ advances by Zacharia Running Bear (Joseph Billingiere), who shoots Rufus with an arrow. When asked why he did it, Zacharia says, “You looked like you were in danger.” In each case, Penelope encounters men who act out of their own sense of virtuousness, only to follow that up with a selfish pass, to which they feel entitled. Centuries of storytelling and unchanged gender roles have created the expectation that the hero rescues the damsel in distress, and together, they live happily ever after. But few stories ever ask what the damsel wants and needs. In the end, Penelope resolves to row into the foggy sea, accompanied only by Butterscotch, to find some unknown place where hopefully she can live without being pestered by insecure men desperate to fulfill their assigned roles.

Damsel debuted at the Sundance Film Festival in 2018 and went ignored after that, never acquiring a wide theatrical release and disappearing into the streaming ether. But here’s a film that infuses an ironic tone into a traditional Western schema, capturing a similar sense of humor, wry commentary, and grim perspective on the West as certain episodes from the Coens’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018). Visually, the Zellners shoot on location in the Utah wilderness and allow the scenery to inform the film’s leisurely pace. Cinematographer Adam Stone employs long and measured shots of rough terrain on horseback, campfire discussion, grand panoramas, masculine posturing, and romantic declarations—the usual Western trappings. The score by The Octopus Project, accompanied by some yodeling by Russell Mael, presents itself in twangy acoustic guitars and banjos without a wink. The presentation might be mistaken for a straightforward genre helping, except for the story’s trajectory. But it’s the Zellners’ subtle juxtaposition of traditional Western motifs and narrative context that turns Damsel into a vital parody suited to the post-#MeToo era.

Damsel debuted at the Sundance Film Festival in 2018 and went ignored after that, never acquiring a wide theatrical release and disappearing into the streaming ether. But here’s a film that infuses an ironic tone into a traditional Western schema, capturing a similar sense of humor, wry commentary, and grim perspective on the West as certain episodes from the Coens’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018). Visually, the Zellners shoot on location in the Utah wilderness and allow the scenery to inform the film’s leisurely pace. Cinematographer Adam Stone employs long and measured shots of rough terrain on horseback, campfire discussion, grand panoramas, masculine posturing, and romantic declarations—the usual Western trappings. The score by The Octopus Project, accompanied by some yodeling by Russell Mael, presents itself in twangy acoustic guitars and banjos without a wink. The presentation might be mistaken for a straightforward genre helping, except for the story’s trajectory. But it’s the Zellners’ subtle juxtaposition of traditional Western motifs and narrative context that turns Damsel into a vital parody suited to the post-#MeToo era.

The narrative’s shift from Samuel to Penelope might be disorienting if one assumes either Pattinson or Wasikowska is the protagonist. Consider instead Henry, who we have followed from the first scenes, when he was a hopeful Pioneer until he met the Old Preacher at the end of his rope. Henry’s wife and child died during childbirth, and he takes on the role of a religious man because it’s available to him. But the Old Preacher warned him about the “shitty” Wild West chewing up and spitting people out, and through the course of the film, he sees that happen to Samuel and experiences it firsthand. Only Penelope has the intestinal fortitude to endure, whereas Henry relies on booze and hopes in vain to find someone (it doesn’t matter who) to give his life meaning. After Zacharia rescues him and Penelope from Anton, Henry proposes a kind of adoption into his tribe. Henry wants to escape his identity at any cost. At this, Zacharia can only ask, “What’s wrong with you?” Henry replies in a wounded, desperate tone, “I need a fresh start.”

Using Penelope’s tragedy as a focal point, Damsel questions the idealistic and destructive assumptions about the West as a land of opportunity and destiny. The Zellners show their characters, Henry above all, projecting great meaning onto the West and its redemptive potential. But as the Old Preacher warns, and the fates of Henry and Samuel illustrate, the West and our dreamy expectations about it can result only in disappointment, disaster, and trauma. Much like the Coens have done, the Zellners play with cinematic conventions, with standards of plot, characters, and themes. They mark their variations with occasional flourishes of slapstick and grotesque humor, dark twists, and new contexts that introduce a critical view of the Western. Damsel is also damn funny, with the ridiculous Pattinson and a severe Wasikowska doing some of their finest work. It is a film that has been overlooked and demands a critical reassessment for its goofy pleasures, sharp commentary, and playfulness with genre traditions.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review