Dallas Buyers Club

By Brian Eggert |

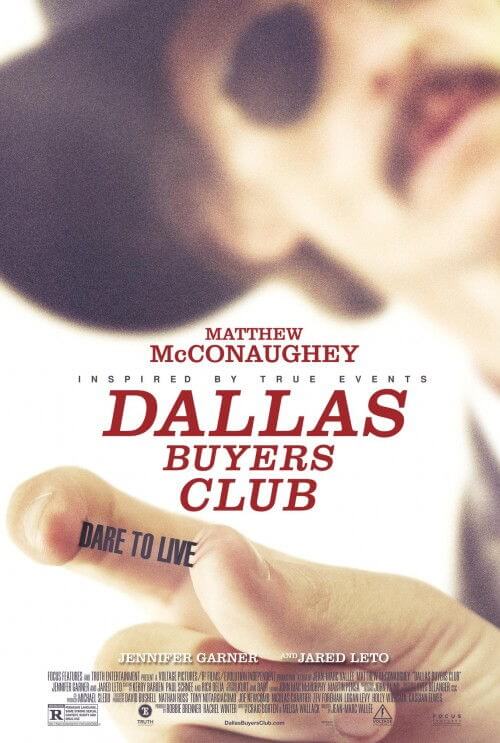

In Dallas Buyers Club, Matthew McConaughey plays real-life figure Ron Woodruff, an electrician by day, quintessential rodeo-ridin’ cowboy and hustler by night, who contracted AIDS from unprotected heterosexual sex. McConaughey appears rail-thin, his southern drawl firmly intact and applied toward his character’s rootin’-tootin’ attitude, frequent cocaine use, bedding of countless prostitutes and junkies, and redneck-standard homophobic remarks. After Woodruff discovers his condition and short 30-day prognosis in 1985, he goes outside of Food and Drug Administration guidelines to find a treatment abroad to buy himself time. But there’s also an opportunity here, and so he launches a “buyers club” wherein participants pay a membership fee to gain access to medications and vitamins otherwise unapproved by the FDA in the treatment of AIDS. Woodruff went on to supply hundreds of suffering people with treatments they wouldn’t have been able to receive in the United States. He died in 1992.

Directed by Jean-Marc Vallée (The Young Victoria) from a screenplay by Craig Borten and Melisa Wallack, Dallas Buyers Club wants to be informative about its period in history. Around that same time in 1985, but before Woodruff finds out he’s HIV-positive, Rock Hudson died of AIDS-related complications and the headlines fill Woodruff and his friends with disgust for homosexuals. This was an age when people still believed AIDS was exclusively a disease among homosexuals; even intravenous drug use was barely mentioned with its causes. Beyond a brief history lies a commentary about medical activism, knowing that the FDA and pharmaceutical corporations work hand-in-hand to approve drugs that will help people but also ensure a hefty profit, though not necessarily in that order. In some cases, a simple protein that could help AIDS victims remains unapproved because, perhaps, it might not turn a profit or too much money has already been spent on another, less effective drug. Whatever bureaucratic reasons dreamed up by the FDA and Feds in the film, they’re not good enough.

But we don’t leave the theater thinking about how The System is broken, how the government is in league with major prescription drug companies, or how many aspects of today’s medical profession are so capitalistic that they’ve forgotten about the good of the patient. Surprising, since the film gives us bureaucratic baddies to despise, such as Michael O’Neill’s moustache-of-authority Fed, or Denis O’Hare’s pathetic company stooge Dr. Sevard. Engineered for maximum tear-jerking effect, Dallas Buyers Club tells Woodruff’s story through his fight for survival against an insurmountable opponent and impossible odds. He travels over borders and smuggles drugs into the U.S. to help primarily gay men improve their symptoms, developing his humanity and acceptance along the way. Jennifer Garner plays a doctor who sympathizes, her role somewhat unessential to the narrative, except to represent Woodruff’s sole relationship with a woman that doesn’t involve a random shag in some dark, grimy corner.

Rather than mull over the injustice of the tortured Woodruff’s need to smuggle to survive, we leave the theater thinking about McConaughey’s performance, the film’s centerpiece, which overshadows all else. After losing 50 pounds for the role, McConaughey continues to reinvent himself as a true actor—most recently in Mud and Killer Joe—as opposed to just cashing paychecks for dull romantic comedies, as he had done for a number of years. He gives a complex turn as a sleazy charmer, complete with emotional and physical vulnerabilities that gradually give way as the story carries on to distressing extremes. Along with his costar Jared Leto—who’s excellent as Rayon, a transvestite AIDS victim, drug addict, and Woodruff’s unlikely business partner—McConaughey’s appearance is daunting and ranges from shockingly thin to just overly skinny, depending on the health of the character, and demands comparisons to Christian Bale’s turns in The Machinist and The Fighter. It’s the kind of performance that was designed to be noticed by Oscar voters, and should be.

Arriving in a time when debates about gay marriage, health advocacy, and medical controversies fill the headlines, Dallas Buyers Club creates only momentary awareness of a problem and doesn’t fill us with the kind of impassioned drive of titles like Sicko or Milk—films that leave us wanting to learn more about their subject and join their cause long after the credits roll. Vallée’s attempts to transform reality into a verité-styled exposé are degraded into a purely human interest story once McConaughey and Leto have finished showcasing their astounding ability to drop weight and hand themselves over to their characters. Nevertheless, the film keeps us watching, even if we know Woodruff won’t live forever and, as history has proved, this will not end with AIDS being cured or the FDA developing a conscience. With Woodruff’s life lessons learned and his hard shell cracked to find a gooey, human center inside, Dallas Buyers Club is a fascinating character study that underplays its own value as a message movie.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review