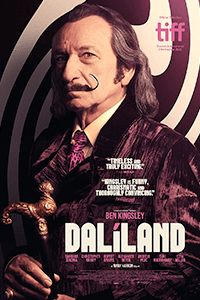

Dalíland

By Brian Eggert |

One of my art history professors at the University of Minnesota told me a story about how she and two other graduate students visited Salvador Dalí at his home in Portlligat in the late 1960s. Upon knocking, the students were surprised to find Dalí open the door with a smile. “Ah, the young scholars,” Dalí greeted them. “You’ve come to see Dalí work,” he said, referring to himself, as always, in the third person. Then Dalí invited the three students inside and led them down a hallway to a door, where he paused and announced, in theatrical fashion, “Now, for Dalí’s latest masterpiece!” He opened the door to the bathroom and gestured for the students to look in the toilet bowl, where they saw a massive deposit of feces. Dalí did not laugh or giggle but looked into the toilet with pride. The students, who admired the surrealist painter, experienced a sharp shift in their preconceived notions about the artist. While this is a crude yet amusing anecdote, it reveals the many facets of Dalí, whose persona often changed according to his audience. This is the subject of Mary Harron’s Dalíland, a fascinating portrait of an artist whose identity is buried underneath layers of self-invention.

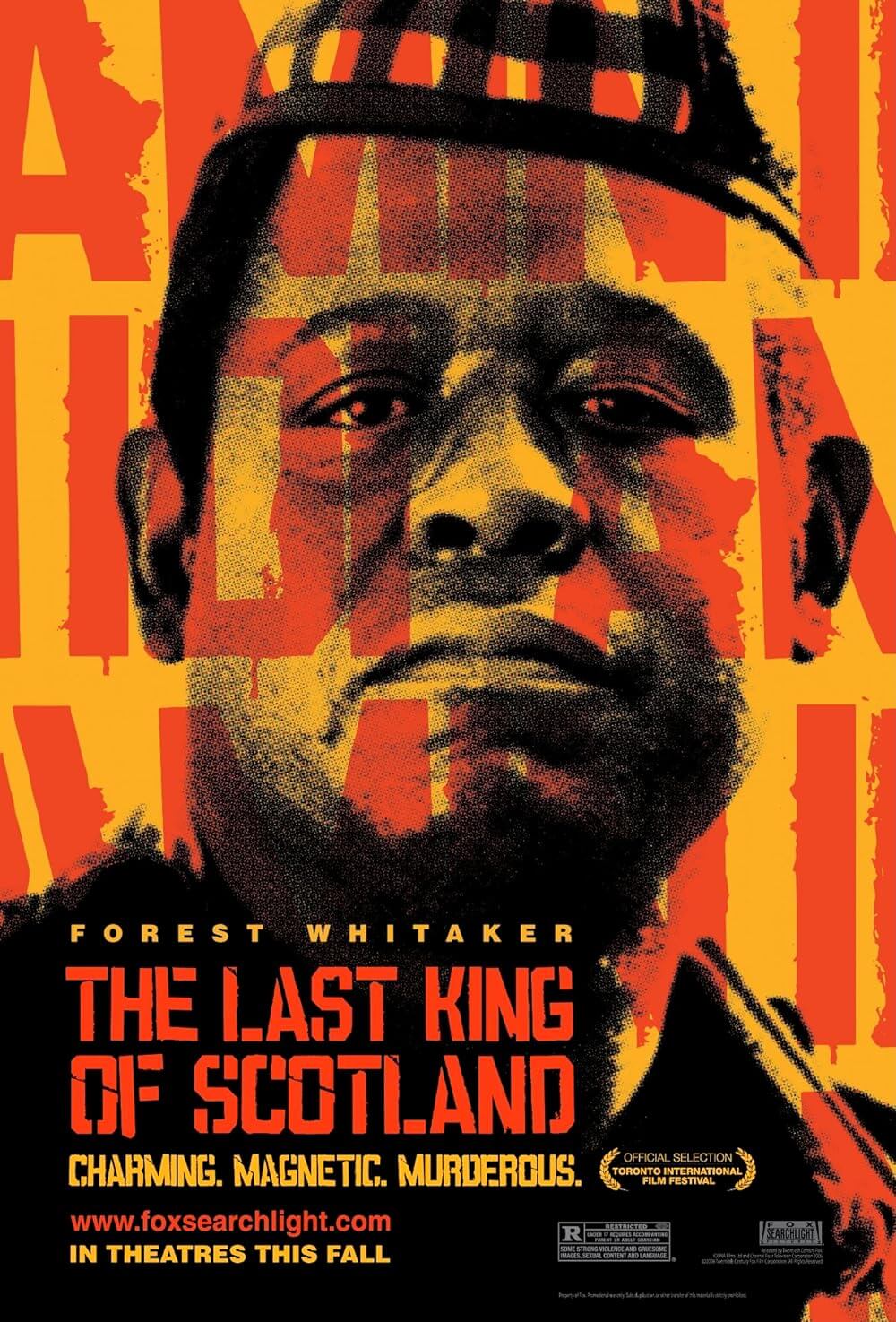

The subject aligns with Harron’s sensibilities, having made a career out of movies about historical icons. But Harron always places a device within the narrative to distance viewers from figures such as Andy Warhol, Bettie Page, and Charles Manson. For instance, with I Shot Andy Warhol (1996), the film is less about the artist than his New York Studio, The Factory, and Valerie Solanas’ peripheral role there. When Harron made The Notorious Bettie Page (2005) for HBO, it wasn’t so much about getting inside Page’s head as deconstructing the era that made her a pin-up model. Charlie Says (2019) put Charles Manson into a story focused on the women he brainwashed. Similarly, Dalíland approaches its subject through the perspective of a young art appreciator, James (newcomer Christopher Briney), who serves as our entry point into the titular world of fine art, excessive parties, and money-grubbing scams involving Dalí, played wonderfully by Ben Kingsley. The setup is familiar, recalling Me and Orson Welles (2008) or My Week with Marilyn (2011) in its external view of a larger-than-life figure.

The bulk of the screenplay by John C. Walsh (Harron’s spouse) takes place in 1974, long after Dalí had been established as the face of surrealism and a household name for paintings such as The Persistence of Memory. The film centers on James, an art school dropout working for a New York gallery manager. James finds himself hired by the Spanish painter in the weeks before an exhibition at the gallery. Much of the early film involves James getting exposed to the bizarre entourage around the eccentric artist, who has a list of peculiarities, from only eating “well-defined shapes” to hiring young women to surround him at parties, all of whom he gives the same name. Likewise, Dalí gives James the nickname “Saint Sebastian,” noting his resemblance to the painting by Gustave Moreau. James must keep Dalí productive to appease Gala (Barbara Sukowa), the artist’s wife and taskmaster who has developed a fixation on the self-obsessed Jeff Fenholt (Zachary Nachbar-Seckel), the young headliner of Jesus Christ Superstar. On the side, James finds himself in a casual affair with one of Dalí’s hangers-on, Ginesta (Suki Waterhouse).

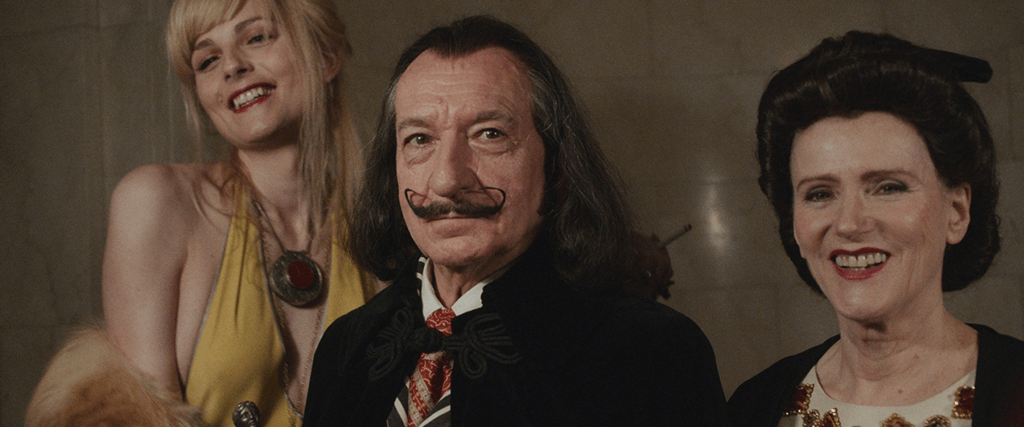

From the outset, Harron shows an interest in characters who mask their true selves in a kind of performance art or serial self-invention. James earns Dalí’s attention by presenting the artist with a book he made, containing photos of the dozens of signatures Dalí has used over the years—a sign that his identity remains a fluid concept. But amid chaotic scenes of Dalí’s expensive lifestyle, Harron and cinematographer Marcel Zyskind capture intimate moments where the surrealist dyes his signature mustache and darkens his eyebrows, then picks out an ostentatious costume, carefully designing his appearance. Moreover, Dalí surrounds himself with similar characters, among them Alice Cooper (Mark McKenna), whose makeup and onstage antics denote his performative identity. Dalí also shows an affinity for drag queens, such as the transgender performer and future pop star Amanda Lear (Andreja Pejić). Ginesta, too, engages in a kind of performance, as does Gala with her wig and affinity for younger men. All of them are outcasts who feel at home in Dalí’s presence, perhaps because, as one character describes him, “I don’t think they’ve invented a word for what Dalí is.”

From the outset, Harron shows an interest in characters who mask their true selves in a kind of performance art or serial self-invention. James earns Dalí’s attention by presenting the artist with a book he made, containing photos of the dozens of signatures Dalí has used over the years—a sign that his identity remains a fluid concept. But amid chaotic scenes of Dalí’s expensive lifestyle, Harron and cinematographer Marcel Zyskind capture intimate moments where the surrealist dyes his signature mustache and darkens his eyebrows, then picks out an ostentatious costume, carefully designing his appearance. Moreover, Dalí surrounds himself with similar characters, among them Alice Cooper (Mark McKenna), whose makeup and onstage antics denote his performative identity. Dalí also shows an affinity for drag queens, such as the transgender performer and future pop star Amanda Lear (Andreja Pejić). Ginesta, too, engages in a kind of performance, as does Gala with her wig and affinity for younger men. All of them are outcasts who feel at home in Dalí’s presence, perhaps because, as one character describes him, “I don’t think they’ve invented a word for what Dalí is.”

Kingsley is excellent as an aging artist whose hands and mind have started to deteriorate. But it’s more fun to watch the character overcome by sudden bursts of inspiration—from his idea of creating the world’s largest penis sculpture to his prints of women’s bare bottoms. At other times, his hypochondria and willful denial of reality feel troublesome, suggesting a deeply wounded and disturbed individual underneath the artifice. Unfortunately, flashbacks to Dalí in the 1930s, where Ezra Miller plays the young artist, do little to illuminate the character or explore his sexual preoccupations. But they do establish the passionate love between him and Gala (the younger version played by Avital Lvova). The few scenes with Miller feel inconsistent and haphazardly included. However, despite their off-screen antics, Harron refused to cut the performer from her film. Even so, Miller’s presence is only a mild distraction and cut in such a way that suggests Harron may have reduced the role, leaving Miller with only a handful of small scenes in which the elder Dalí stands alongside James and watches his past unfold in remembrance. By comparison, Briney, as the self-assured and somewhat passive protagonist James, barely registers in his scenes, with his underwritten character serving as a normalizing force amid so many compelling oddballs and deviants.

Most painters and sculptors who lived through the modern art investment boom of the 1960s saw what was once an almost spiritual process of making and appreciating art mutate into an intense commodities market. Harron touches on how Dalí’s wife and his manager (Rupert Graves) exploit their cash cow, from forcing him to work to creating unauthorized reprints sold as lithographs. Detours aside, Dalíland is about a period in the artist’s life after his popularity had stalled, when he became desperate to maintain his lifestyle, and his status in the culture became a novelty act. But Harron has an affinity for such outsiders, as her filmography suggests. So even though Alex Mackie’s editing feels clunky and the visuals seem desaturated to the point of flatness, the director finds tenderness in the relationships between Dalí, Gala, James, and Amanda. The film doesn’t answer the question, “Who is Salvador Dalí?” But it does reveal his status as an icon among those who adopt new identities, whether it’s their true face, as in Amanda Lear’s case, or simply one in a collection of performative masks. Dalí believes that the mask is his true face, and Harron leaves it to the viewer to decide whether or not that’s tragic.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review