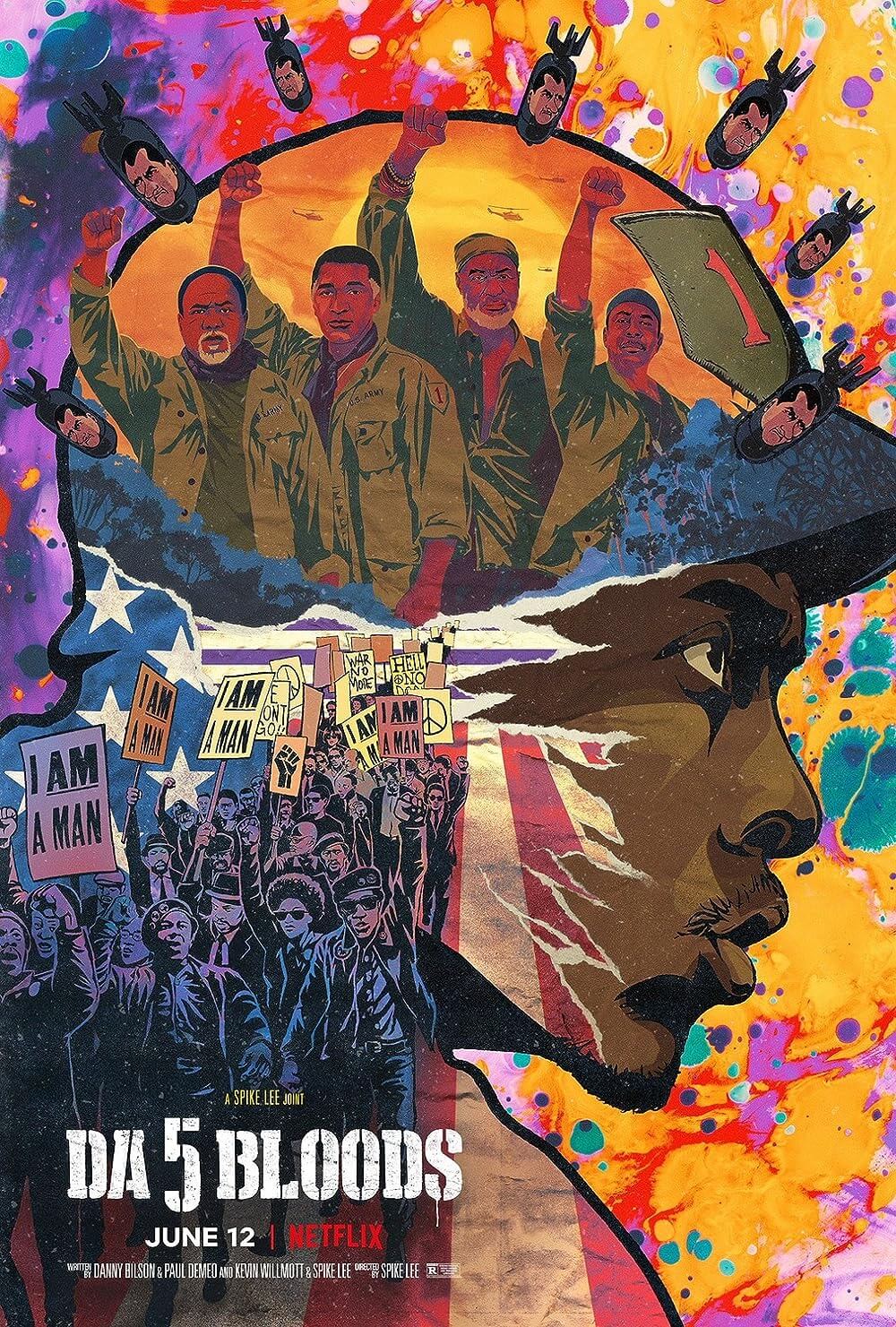

Da 5 Bloods

By Brian Eggert |

Da 5 Bloods is another jolt of Spike Lee electricity. It crackles in every which way. The film feels volatile, yet its voice has undeniable power. In the story, four Black Vietnam vets return to the country that left them scarred by battle, and they search both for their squad leader’s remains and the millions in gold bars they stashed during their tour. Lee jump-starts conversations about American history, Black Lives Matter, Hollywood cinema, and the presidency of Donald Trump—subjects that were recently amplified by the George Floyd protests around the world. His approach is energizing and wildly playful, similar to his 2018 breakout, BlacKkKlansman, and before that Chi-Raq in 2015. The live wire quality of his filmmaking keeps us alert, unsure of what to expect next. Even though the film concerns thoroughly explored material, the “American War” in Vietnam, Lee blends his formal control with tonal experimentation. It would be easy to criticize his smorgasbord approach as unfocused, but as ever, there’s a genius behind his charged style. His jam-packed authorial signatures are all over Da 5 Bloods, and like his best films, it’s not easily processed or digested. It leaves us angry, moved, and often shocked. But Lee’s tangential aesthetic, combined with his exploration of historical and contemporary contexts, proves to be the cinematic equivalent of an electrical current.

The film opens with footage of Muhammad Ali from 1978, telling members of the press that he won’t fight in Vietnam because “they didn’t rob me of my nationality.” What follows is a series of clips that contextualize Black history during the years of the Vietnam war. Kwame Ture stating that “America has declared war on Black people” in 1968. The Kent State massacre. Planes dropping Agent Orange (also Lee’s name for Trump) on Vietnamese fields. The self-immolation of monk Thích Quảng Đức. America’s bombing of children with Napalm. And protests about how soldiers of color returned home from Vietnam only to face American racism. The hypocrisy that America expects Black men to fight in its wars, yet subjects them to systemic racism at home, is a theme Lee has explored before in his World War II epic Miracle at St. Anna (2009). At the same time, Lee’s use of this real-world imagery creates a conversation, an almost Brechtian awareness of reality that forces the viewer to place the film in a historical framework. The viewer is at once conscious of the discussion, yet the screenplay, penned by Lee and Kevin Willmott, based on a script by Danny Bilson and Paul De Meo, doesn’t sacrifice its dramatic impact for its commentaries.

Lee’s approach to Da 5 Bloods borrows a tactic from Ali—the rope-a-dope. He draws the viewer into an accessible story about four old-timers searching their painful memories and violent past, but rather than healing those wounds as a more conventional film might, he confronts how they remain festering and open. Within the first scenes, you might form expectations of what will unfold over the next two-and-a-half hours. The quartet, who call each other “Bloods,” reconnect in Ho Chi Minh. Their reunion is full of hugs and chummy remarks about getting old. Otis (Clarke Peters), the even-keeled former medic, is our entry point. There’s also Eddie (Norm Lewis), who financed the trip; the resident joker, Melvin (Isiah Whitlock Jr.), who uses the trip to escape married life; and Paul (Delroy Lindo), who continues to harbor anger about the war, having been scarred the most by PTSD. Paul has also embraced the Trumpian ideology—complete with MAGA hat—of xenophobia and American exceptionalism, much to the dismay of his former fellow soldiers. Still, they have come together, backed by letters from the Pentagon and Vietnamese government, to find what’s left of their beloved friend and former leader, “Stormin’ Norman” (Chadwick Boseman).

Lee’s approach to Da 5 Bloods borrows a tactic from Ali—the rope-a-dope. He draws the viewer into an accessible story about four old-timers searching their painful memories and violent past, but rather than healing those wounds as a more conventional film might, he confronts how they remain festering and open. Within the first scenes, you might form expectations of what will unfold over the next two-and-a-half hours. The quartet, who call each other “Bloods,” reconnect in Ho Chi Minh. Their reunion is full of hugs and chummy remarks about getting old. Otis (Clarke Peters), the even-keeled former medic, is our entry point. There’s also Eddie (Norm Lewis), who financed the trip; the resident joker, Melvin (Isiah Whitlock Jr.), who uses the trip to escape married life; and Paul (Delroy Lindo), who continues to harbor anger about the war, having been scarred the most by PTSD. Paul has also embraced the Trumpian ideology—complete with MAGA hat—of xenophobia and American exceptionalism, much to the dismay of his former fellow soldiers. Still, they have come together, backed by letters from the Pentagon and Vietnamese government, to find what’s left of their beloved friend and former leader, “Stormin’ Norman” (Chadwick Boseman).

Rail-thin and a downright mythic screen presence, Boseman once again plays an important (if fictional this time) Black hero. He has made a name for himself in by-the-numbers biopics playing icons of African American culture from sports (Floyd Little and Jackie Robinson in The Express and 42, respectively), music (James Brown in Get on Up), civil rights (Thurgood Marshall in Marshall), and comic books (Black Panther in the MCU). It’s a minor role for Boseman, and the character speaks few lines, but he feels essential because everyone talks about Stormin’ Norman. The Bloods have constructed their own mythos around Norman, who taught them how to survive as soldiers and human beings. He also taught them about Black history, from Crispus Attucks’ death in the Boston Massacre to Milton Olive III, who became the first Black Medal of Honor recipient for his self-sacrifice by jumping on a grenade to save his comrades—moments that Lee will draw upon later in the film. Norman’s death wounded Paul the deepest, having worshipped him “like a religion.” But how Norman died, and the nature of Paul’s trauma, become crucial reveals later in the film.

When a flashback of their wartime experiences alongside Stormin’ Norman bursts onto the screen, Lee’s visual style shifts from Newton Thomas Sigel’s crisp and modern photography to something reminiscent of archival footage. The 2.35:1 widescreen aspect ratio narrows before our eyes to the boxy Academy ratio, and the images appear grainy and fuzzy, as if the action was captured with a Super 8 camera. Norman appears youthful alongside older, graying versions of the four survivors, who seem to place their current selves into their memories of the past (there are no ugly de-aging effects to distract us). The sequence shows the Bloods shot down in a helicopter and then engaging in a firefight near a downed American plane. Inside, the men find a metal case filled with millions in gold bars the CIA intended to support South Vietnamese troops. Back in the present day, we learn the Bloods buried the gold and have returned to reclaim their bounty. In a tender subplot, Otis reconnects with Tien (Le Y Lan), with whom he had a relationship during the war. She arranges a deal with a French fence (Jean Reno) to move the gold out of the country illegally. Some plan to use the money to help African Americans; some have more selfish ambitions. Paul’s son David (Jonathan Majors), Otis’ godson, has joined them, concerned about his father’s mental health. After arranging a deal, the newly assembled group of five heads into the jungle.

Lee evokes a rich cinematic history along the way. His first and most apparent influence is Apocalypse Now (1979), which he calls out more than once in the first half with sun-drenched wartime images and “Ride of the Valkyries” playing over scenes on a boat upriver. To be sure, the film journeys into the heart of darkness by the halfway point, where it transitions into The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) mode. Their personalities clash when their boat voyage becomes a hike on rough terrain. They begin to bicker and shout, and the dynamic changes when one of them discovers that Otis brought a gun. All at once, Paul takes on the Humphrey Bogart role—a character so paranoid and angry that he’s bound to destabilize the group—and becomes its threatening leader. Once they find the gold, the men dance like Walter Huston’s prospector, but their joy descends into infighting. They’re also joined by members of an organization that defuses land mines and bombs left over from the war—played by Mélanie Thierry and two stars from BlacKkKlansman (Paul Walter Hauser and Jasper Pääkkönen)—complicating matters. The Bloods also find themselves confronted by locals who believe the gold belongs to them. When each of these elements clashes in the jungle, Lee’s most poignant reference is to The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), and that film’s final line, “Madness!”

Lee evokes a rich cinematic history along the way. His first and most apparent influence is Apocalypse Now (1979), which he calls out more than once in the first half with sun-drenched wartime images and “Ride of the Valkyries” playing over scenes on a boat upriver. To be sure, the film journeys into the heart of darkness by the halfway point, where it transitions into The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) mode. Their personalities clash when their boat voyage becomes a hike on rough terrain. They begin to bicker and shout, and the dynamic changes when one of them discovers that Otis brought a gun. All at once, Paul takes on the Humphrey Bogart role—a character so paranoid and angry that he’s bound to destabilize the group—and becomes its threatening leader. Once they find the gold, the men dance like Walter Huston’s prospector, but their joy descends into infighting. They’re also joined by members of an organization that defuses land mines and bombs left over from the war—played by Mélanie Thierry and two stars from BlacKkKlansman (Paul Walter Hauser and Jasper Pääkkönen)—complicating matters. The Bloods also find themselves confronted by locals who believe the gold belongs to them. When each of these elements clashes in the jungle, Lee’s most poignant reference is to The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), and that film’s final line, “Madness!”

Lee doesn’t shy away from depicting the ugly truth of war, which is what Da 5 Bloods becomes in the second half. It’s a relentless and bloody film in that respect. However, the images of wartime atrocities that flash onscreen (including frames of the actual My Lai Massacre, where U.S. troops raped women and children, then slaughtered hundreds of unarmed civilians) remind us that this violence isn’t escapist. The earlier flashback sequences in a helicopter may show evidence of subpar CGI, but more than once, Lee shocks and disturbs the viewer with realistic bloodshed. He also orchestrates unforgettable moments of tension, such as a sequence when David realizes he has stepped on a land mine and will explode if he moves. The sequence is so terrifying because, a minute earlier, we see just what happens to the human body when it steps on an explosive device. And when the rousing finale may seem to enter cathartic shoot-em-up territory, Lee makes every choice intentional, and every death. The gold, too, takes on multiple meanings—first as the Bloods’ hope to find some measure of victory from their wartime experiences, then as a claim to reparations, and then as a symbol of the American government’s false promises to the South Vietnamese.

Though Da 5 Bloods is an ensemble piece and the entire cast shines, Lindo’s complex and angry performance is the standout. Paul’s short temper and inner pain drive the conflict and, eventually, enrich the character. After three memorable parts in Malcolm X (1992), Crooklyn (1994), and Clockers (1995), Lindo hasn’t appeared in a Spike Lee joint for twenty-five years. Yet, he delivers perhaps his finest performance as Paul, a character who wants Trump to build a wall and shows nothing but disdain for anything un-American. Lee portrays the character as writhing in his own skin, incapable of confronting his past or accepting responsibility for his actions (“There were atrocities on both sides,” he says, recalling Trump’s statements about the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville). And when Reno’s character puts on Paul’s MAGA hat, Lee remarks about the kind of people drawn to such a symbol—it transitions from an unempathetic and angry man to a duplicitous and opportunistic one. Though Lee questions Paul’s political ties, he also reveals their tragic origin. The camera faces Paul in an extended monologue, where the character seems to lose his sanity in the jungle. But the character’s paranoid rant against the U.S. government (“You can’t kill me”) develops into a scene where Paul finally confronts the dark specters of his past. At this moment, it feels like the best single performance in any of Lee’s films.

Structurally and stylistically, Da 5 Bloods earns the lengthy runtime by zig-zagging through its epic scope. Similar to Bamboozled (2000) or Chi-Raq, Lee’s film has an experimental quality, allowing for individual scenes that immerse the viewer, while it also comments on the world outside the film. In a technique reminiscent of Jean-Luc Godard, Lee breaks from straightforward storytelling to engage in a polemical conversation with the viewer. At any moment, he might cut to a painting of the Boston Massacre or recall an image from Apocalypse Now. He also inserts scenes with Hanoi Hanna (Veronica Ngo), who reads propaganda to her “soul brother” listeners on Vietnamese radio, asking them why they’re fighting this war. When one of her broadcasts informs the Bloods about the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., they begin to question what awaits them at home. Lee also openly discusses Hollywood movies like First Blood (1982) or Missing in Action (1984), which tried to turn America’s loss in Vietnam into a belated victory—but no one wins in Da 5 Bloods. Elsewhere, Lee’s aspect ratio changes once again to 1.85:1 in the second half, which allows this Netflix film to fill our television screens and further immerse us into the sheer scope and beauty of the filmmaking—many of the shots, captured on location in Vietnam, result in awe. It might seem like an untidy collage, except Terence Blanchard’s soulful score provides cohesion, as do the omnipresent Marvin Gaye tunes in the second half.

Structurally and stylistically, Da 5 Bloods earns the lengthy runtime by zig-zagging through its epic scope. Similar to Bamboozled (2000) or Chi-Raq, Lee’s film has an experimental quality, allowing for individual scenes that immerse the viewer, while it also comments on the world outside the film. In a technique reminiscent of Jean-Luc Godard, Lee breaks from straightforward storytelling to engage in a polemical conversation with the viewer. At any moment, he might cut to a painting of the Boston Massacre or recall an image from Apocalypse Now. He also inserts scenes with Hanoi Hanna (Veronica Ngo), who reads propaganda to her “soul brother” listeners on Vietnamese radio, asking them why they’re fighting this war. When one of her broadcasts informs the Bloods about the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., they begin to question what awaits them at home. Lee also openly discusses Hollywood movies like First Blood (1982) or Missing in Action (1984), which tried to turn America’s loss in Vietnam into a belated victory—but no one wins in Da 5 Bloods. Elsewhere, Lee’s aspect ratio changes once again to 1.85:1 in the second half, which allows this Netflix film to fill our television screens and further immerse us into the sheer scope and beauty of the filmmaking—many of the shots, captured on location in Vietnam, result in awe. It might seem like an untidy collage, except Terence Blanchard’s soulful score provides cohesion, as do the omnipresent Marvin Gaye tunes in the second half.

Similar to most of Lee’s most challenging and lasting films, Da 5 Bloods is full of discordant tones and severe dislocations from one scene to the next. It’s often funny, exciting, and enjoyable as a story about greed and war, just as BlacKkKlansman worked on a fundamental level as a cop thriller. It features terrific performances across the board, and, unquestionably, Lindo will be recognized with an award or two. But it’s also a reflector. Lee has a way of transcending the messy, dissonant vibrations of his work to create a resounding harmony—there’s a method to the madness onscreen, which becomes painfully clear and forces prolonged consideration of the Black experience and civil rights in American history. If there had to be just one theme pulsing through Lee’s more than thirty years as a filmmaker, this would be it. He leaves the viewer with footage of MLK quoting Langston Hughes: “America never was America to me, and yet I swear this oath: America will be.” The speech was given precisely one year before his assassination, and the implications of that are haunting. With it, Lee frames the story into one that mourns the past and remembers its ghosts, even as he speaks with a troubling relevance that makes his film seem engineered for today, and tomorrow.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review