Cuckoo

By Brian Eggert |

One of the more what the fuck is going on here experiences I’ve had with a movie in recent memory, Cuckoo out-weirds and out-thrills independent distributor Neon’s other summer release, Longlegs. That breakout serial killer hit shattered all box-office projections, earned widespread critical praise, and became an audience favorite. But I didn’t really see the appeal of its oppressive style and stilted characters. Cuckoo is something altogether different and less easily categorized, and the promotional material about the film has been refreshingly elusive, offering no real answers about what the story entails. Finding out what’s happening is part of the fun. Early scenes make vague allusions. Ominous shadows, talk of “nestlings,” and adolescents “escaping” their homes—all inside the dense forests surrounding a resort in the Bavarian Alps. Picturesque environment aside, this is nightmarish material because the filmmakers conceal answers until late into the proceedings, leaving us unnerved and disoriented from the many bizarre turns. And I must say, after reviewing thousands of movies over the years, it’s a pleasure to watch something that doesn’t follow an instantly recognizable schematic.

Hunter Schafer plays Gretchen, a 17-year-old relocating to Germany with her father Luis (Marton Csokas), stepmother Beth (Jessica Henwick), and their non-speaking child Alma (Mila Lieu). Eight years ago, around the time they conceived Alma, Luis purchased some land in these mountains. They have an elaborate house there, and they’ve been enlisted to help design a new building for their friend, Herr König (Dan Stevens), some manner of scientist and owner of the local resort. Upon meeting König, Gretchen at once picks up on a culty vibe surrounding him, be it his chummy relationship with Luis or the lingering presence of Dr. Bonomo (Proschat Madani), König’s friend who runs a nearby Chronic Disease Treatment Center. Gretchen vows to return home, calling her unresponsive mother in the United States to explain that living with her father isn’t working. But she never hears back. If the setting feels off somehow at first, it becomes downright sinister as the film carries on, devolving into a flat-out fright fest.

To say anything more than what appears in the trailer might do you a disservice, so I will remain vague while painting the picture. When Gretchen takes a job at Herr König’s resort, she notices more oddities. More than one woman guest at the hotel vomits in the lobby or outside. König also insists that Gretchen not ride her bike home from work at night; she should lock the door and wait inside until he picks her up. What’s out there, we wonder? And does it have anything to do with Alma having a seizure, where time appears to skip and even repeat a few beats, while outside, animal sounds screech in the woods? Luis and Beth accuse Gretchen of being the “disruption” that caused Alma’s incident. But Gretchen, too, seemed to vibrate during the chaotic moment of Alma’s seizure. And if feeling displaced and alienated weren’t enough, being blamed for causing her kindly half-sister’s convulsions adds to Gretchen’s desire to leave.

Director Tilman Singer, working on his second feature after 2018’s Luz, conceives of several inspired sequences that leave us chilled to the bone. One of them finds Gretchen on a bike, ignoring König’s advice and riding home at night—with headphones on, no less. A shadow from the overhead street light reveals that she’s being chased by a woman with glowing red eyes, hand outstretched, screaming like a banshee. What is this thing? Not a traditional human. A traditional banshee, perhaps? Doubtful—it’s the wrong part of Europe for such folklore. The answers, as ever, prove impossible to guess and, ultimately, less important than the ride Singer has in store, which seems so atypical of today’s persistent horror themes and motifs as to deserve admiration. It’s not that, in the end, the viewer can still say that they’ve never seen anything like it. I thought a lot afterward about H.G. Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896) and, more recently, The Animal Kingdom (2023). But maybe that’s saying too much.

Director Tilman Singer, working on his second feature after 2018’s Luz, conceives of several inspired sequences that leave us chilled to the bone. One of them finds Gretchen on a bike, ignoring König’s advice and riding home at night—with headphones on, no less. A shadow from the overhead street light reveals that she’s being chased by a woman with glowing red eyes, hand outstretched, screaming like a banshee. What is this thing? Not a traditional human. A traditional banshee, perhaps? Doubtful—it’s the wrong part of Europe for such folklore. The answers, as ever, prove impossible to guess and, ultimately, less important than the ride Singer has in store, which seems so atypical of today’s persistent horror themes and motifs as to deserve admiration. It’s not that, in the end, the viewer can still say that they’ve never seen anything like it. I thought a lot afterward about H.G. Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896) and, more recently, The Animal Kingdom (2023). But maybe that’s saying too much.

Singer’s screenplay delivers one unexpected story moment after another so effectively that one might overlook his equally jarring formal techniques, which complement what ventures into body horror blended with a creature-feature. Terel Gibson and Philipp Thomas deploy an editing style that might be accused of being choppy if not for how intentional the choices feel, leaving us with a sense that something is missing—as if they have stolen moments in time from the audience. Cinematographer Paul Faltz’s camera movements swoosh, glide, and rotate, giving the visuals an off-kilter quality like the narrative. The same is true of the excellent soundtrack and score by Simon Waskow. But somehow, Stevens is Tilman’s most effective device, using his aptitude for German to affect a creepily clinical energy that gives way to disturbing revelations. At one point, he tells Gretchen, “You’re here because you belong here.” Her response is priceless, and Schafer is nothing short of fantastic in the part.

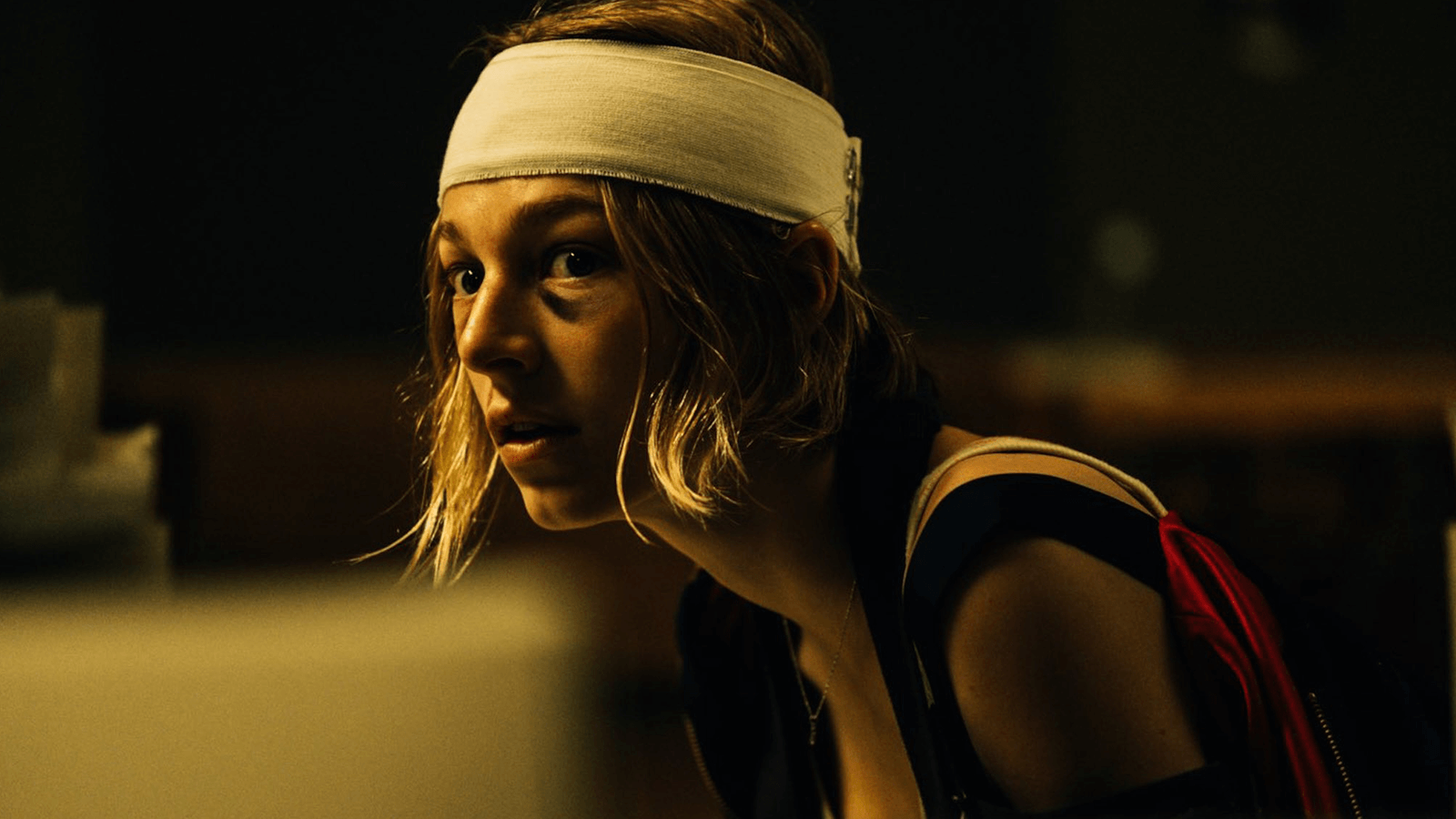

Along the way, Gretchen begins to look how we feel; she accumulates a head wound and bandage, bruised face, and broken arm during various accidents and attacks. She has been pulled through the unthinkable, and unlike most movie characters, she has the physical wear to prove it. There’s not much by way of characterization for her, apart from a predictable tragic backstory. Nonetheless, she develops a heartfelt relationship with her half-sister that sneaks up on you. Best of all, Cuckoo delivers an unpredictable ride that, even if where it ends up feels somewhat unexceptional, remains engrossing from start to finish. It doesn’t operate in the typical visual language and story beats that viewers have come to expect from commercial thrillers, and every time Tilman tries something a little odd or weirder than usual, it’s refreshing. And it’s a mild relief to say this messed-up Neon release lives up to its hype, at least, for this critic, better than Longlegs did.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review