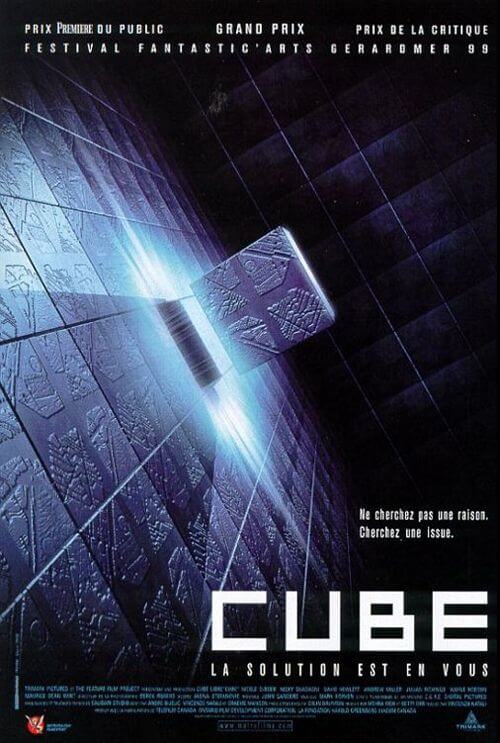

Cube

By Brian Eggert |

Vincenzo Natali’s Cube extends a scenario seemingly straight from The Twilight Zone for the duration of a full-length feature. Though filled with sharp ideas and a setup worthy of Franz Kafka, the film’s distractingly low budget takes away from its enjoyment. Whether or not it appeals to you depends on your ability to forgive some mediocre acting and the occasionally cringe-inducing special effects for its paranoia and mathematical authenticity. No doubt its underdog presence on the indie market (combined with a considerable amount of bloody violence) has sustained this film’s cult status among audiences since its release in 1998, allowing for two hammy sequels and a slowly progressing career for its director.

The mind-bending thriller opens with six strangers who awake to discover they’re inside an enclosed, cube-shaped room of ultramodern design. Each has your typical “trapped in an elevator” character generalities: The cop Quentin (Maurice Dean Wint); the doctor Holloway (Nicky Guadagni); the escape artist Rennes (Wayne Robson); the mathematician Leaven (Nicole deBoer); the cynic Worth (David Hewlett). Each conspicuously named after a prison, the characters have no idea how they arrived there, or who has gone to the trouble of collecting them. They speculate if they’ve been abducted by aliens, or if the government has kidnapped them for some cruel survey. But the film never reveals the purpose of their presence in the cube, rather just forces the characters to confront the situation at hand.

Each of the six walls in their numbered room has a hatch at the center. When they move from room to room through these hatches, they find some rooms are booby-trapped. One of the detainees is diced by a net of wires; another is sprayed in the face with corrosive acid. The deaths are gruesome, but this isn’t a film about elaborate displays of gore. It’s about the clever use of a single set piece, and about the mathematical logic that pertains to how they escape. Math gurus will be able to tell there’s some truth to the reasoning behind one character’s assessment of where they are within the entire complex of cubed rooms, and if not, the screenplay by Natali, André Bijelic, and Graeme Manson sounds reasonable enough in terms of its numbers.

The Toronto production for the Canadian Film Centre’s First Feature Project was shot for $365,000 Canadian, extending every dollar. It was filmed in a single room of 14 cubed feet, with five sets of interchangeable colored panels that give the illusion of varying rooms. Of the six hatches that appear in the room(s), only one worked. And so, through good storytelling and clever editing, the filmmakers dupe us into believing there are hundreds upon hundreds of rooms, each with six possible ways out—either around the characters, above their heads, or at their feet. The outcome is an effective sense of space and suspension of disbelief.

Despite the production’s resourcefulness with its meager budget, Natali and his cinematographer Derek Rogers demonstrate with nearly every shot how the suffocating space limits them visually. Shot compositions are bland, and because of the close quarters, the hand-held camerawork consists of an overuse of close-ups with wide-angle lenses. As a result, watch the film today and it appears produced for television, with its soft grain and substandard computer effects. The Toronto-based effects company C.O.R.E. donated their services to support a local production, but their contributions are the cheapest, most obviously inferior aspect of the film. When the set shakes as rooms move, or when the room’s gizmos attack via computer-animated weaponry, the viewer cannot detach themselves from how slapdash it appears.

And yet, it’s difficult not to admire a film like Cube, even if the result isn’t completely satisfying. Natali establishes themes of Kafkaesque isolation and unawareness, combined with a limited cast in a confined setting—all signatures that have lasted throughout the director’s career, from Cypher and Nothing, up until his most recent effort, the Sundance hit Splice. The film comes so close to greatness that you can taste it, enough to hope Natali will return to this material, perhaps even remake his own film à la Michael Haneke with Funny Games. In the end, its possibility is simply too vast to ignore, but the downfalls are simply too apparent to dismiss.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review