Reader's Choice

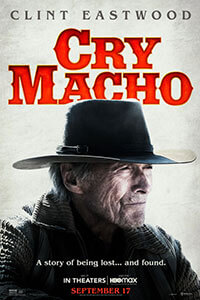

Cry Macho

By Brian Eggert |

At 91, Clint Eastwood’s work remains steady. He still makes a feature every year or two, some better than others, and he still works in that leisurely yet elegant style that has marked much of his twenty-first-century output. Lately, for obvious reasons, he’s been in looking back mode. Eastwood’s last few movies have celebrated so-called American heroes from Chris Kyle to “Sully” Sullenberger to Richard Jewell. And when Eastwood himself appears onscreen, it’s in a role that relies on his screen legacy of roguish characters, some of whom perform good deeds. There’s also been talk of retirement for well over a decade, going back to his now-iconic “get off my lawn” role in Gran Torino (2009). Every new part seems to be his final statement on his career—especially since he’s usually playing characters that reflect himself, or at least lend themselves to such a reading. There’s talk that his latest, Cry Macho, will be his final film either in the director’s chair or in front of the camera. But really, it’s just the latest in a protracted farewell tour to moviegoers.

Based on the 1975 novel by N. Richard Nash, the screenplay, co-written by Nash and Nick Schenk, harkens back to Eastwood’s heyday playing gunslingers and flawed men. Here, he’s Mike Milo, a former cowboy and withered rodeo star who used to work for Howard (Dwight Yoakam) in Texas. Howard’s clumsy expositional lines in the first scene give flavor to Mike’s backstory, complaining that Mike’s glory days came “before the accident, before the pills, before the booze.” However, Howard sets aside his complaints to enlist Mike for a mission to repay an old favor: he compels Mike to travel to Mexico to recover his 13-year-old boy named Rafo (Eduardo Minett) from his Mexican ex-wife. Mike begrudgingly agrees and, when he eventually locates Rafo, he finds the boy clinging to a cockfighting rooster named Macho—a symbol of youthful single-mindedness and masculine aggression. Over the course of their long journey back to Texas, fraught with prying police and local trouble, Mike teaches Rafo that being tough isn’t everything.

Like his character in The Mule (2018), Eastwood plays a worn yet almost benevolent figure whose flaws remain negligible next to his age and experience. Troubled past aside, Mike is a wise old owl the world cannot do without. Everywhere he goes, he helps others, showing them how to do things the right way. We wonder how these characters would ever get along in life without Mike’s help. Touting his virility, he breaks horses, outsmarts bad guys, and oh, the women—younger, beautiful women cannot help themselves around him. A morally compromised woman in lingerie throws herself at him, and Mike politely declines (which is more than his character from The Mule would have done). Another woman, Marta (Natalia Traven), earns Mike’s affection because she keeps a God-fearing household and teaches him to make homemade tortillas. Meanwhile, the flavorless Rafo, the innocent boy with two unreliable parents, soon looks to Mike as a father figure (or maybe grandfather figure). It begins to feel like a vanity project for Eastwood to say, “I still got it!”

Set at an easygoing pace with conflicts that slow the pulse, Cry Macho offers a dramatic turn here and there, not one of which has much consequence. It’s a road movie, and we can see the developments coming a long way down the highway. The minimal plot emphasizes the screenplay’s old-fashioned scenes where the white old-timer offers Mexican characters sage advice. And the relationship between Mike and Rafo feels like something out of a live-action Disney movie from the 1960s. Fortunately, Ben Davis’ handsome cinematography captures some pretty scenery, and Mark Mancina’s score gives the story a quiet personality, all of it composed with Eastwood’s seasoned confidence behind the camera. Onscreen, Eastwood is a little shakier, more horse-voiced, and grumblier than usual, making his character’s physical feats less believable. But the point, I suppose, isn’t about the story—it’s about watching a living legend do his thing.

Eastwood, whose onscreen persona ranges from tough guys such as Harry Callan to more introspective and tortured souls such as William Munny, isn’t subtle about Cry Macho’s thematic notes on masculinity and how it changes between youth and old age. The screenplay slathers the theme over the proceedings, and Eastwood’s straightforward direction leans into it. “You used to be strong, macho,” observes Rafo. “Now you’re nothing.” Looking narrow-eyed and weary, Mike replies, “I used to be a lot of things… I’ll tell you somethin’, this macho thing is overrated.” Cry Macho looks back on a life of hardness with sensitivity and mild humility, even while it also venerates Eastwood’s particular breed of likable, albeit thorny and not-always-redeemable characters. There’s not much nuance or dimension to the movie, but like Mike, and often Eastwood, it gets the job done—only now it’s a little slower, a little blander, and decidedly less memorable.

(Note: This review was originally suggested, commissioned, and posted on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review