Crimes of the Future

By Brian Eggert |

Artists and political revolutionaries make a statement by extracting “neopathic” organs during live surgical performances in David Cronenberg’s evocative dystopian vision, Crimes of the Future. Strange as that sounds, it’s a familiar tale about radicals trying to push humanity forward from the fringes of society and physiology; at the same time, the old guard bent on bureaucracy and conventional biology tries to repress them. The Canadian auteur’s first film in eight years supplies his thesis about the rebellious nature of art, but it’s also powerful enough to conjure all manner of readings. The film’s themes, including the body, progress, nonconformity, tradition, and oppression, could have contemporary parallels from gender identity to abortion rights to ecological change. There’s no limit to the ways those in power will try to curb growth and remove agency by adhering to outmoded doctrines, often in violent and traumatic ways. Cronenberg presents these ideas through a science fiction lens, using storytelling devices that harken back to his most iconic films steeped in defiant technologies, new flesh, and corporate espionage. Although fuelled by discussions of the artistic process and political machinations, and their inevitable collision, one thing remains true for Cronenberg: “Body is Reality,” a slogan that appears on a tube TV during one of the film’s unsettling live performances, and doubles as the director’s motto.

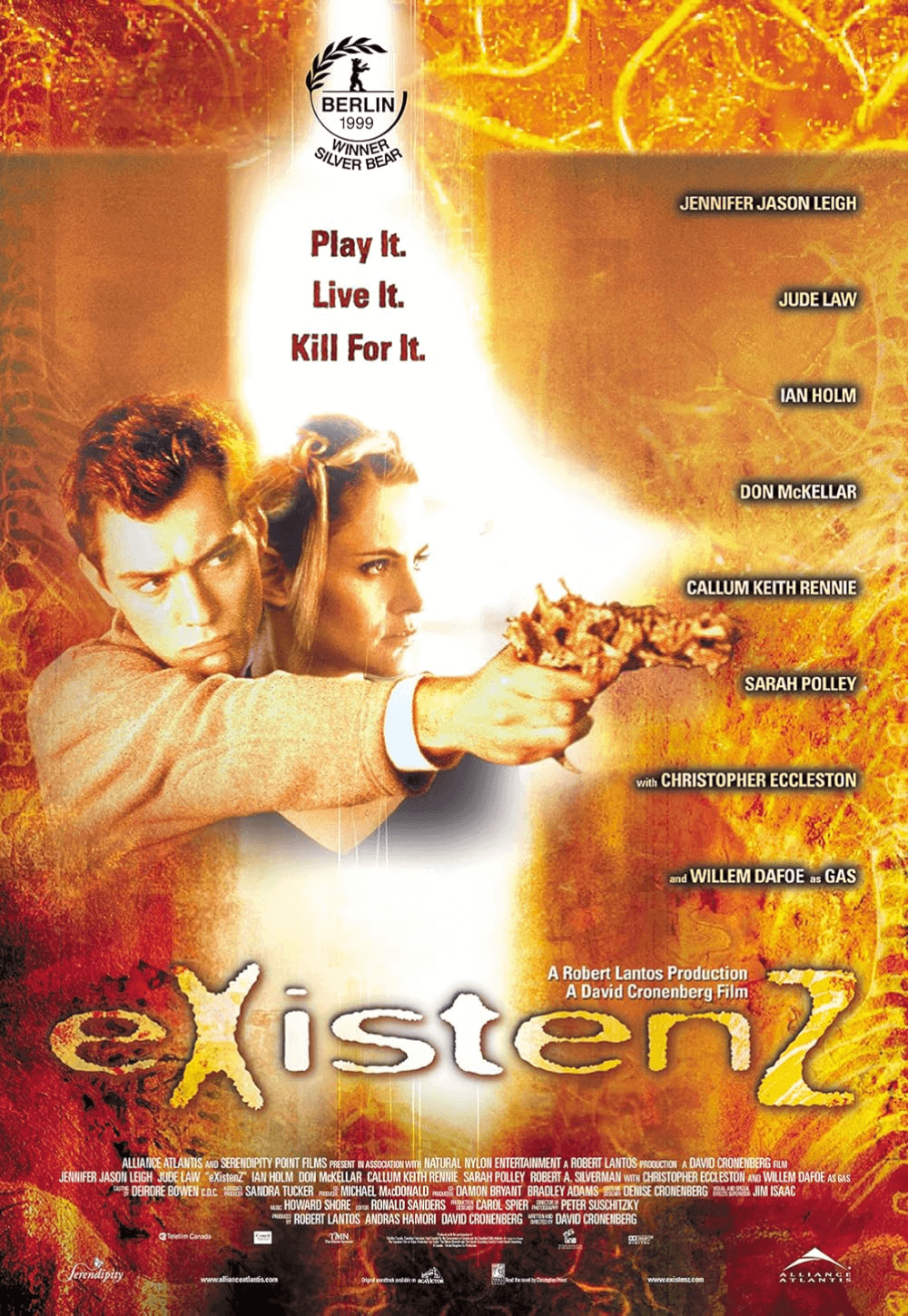

Crimes of the Future finds Cronenberg returning to a mode of body horror he hasn’t explored in over two decades. After he adapted Spider in 2002, his output became relatively normalized and arguably more commercial with titles such as A History of Violence (2005), Eastern Promises (2007), and A Dangerous Method (2011), if no less concerned with how various institutions and concepts shape the body. But after lighting the match to Hollywood with Maps to the Stars (2014), it seemed like either Cronenberg had backed away from directing or the industry had ostracized him. His return signals not only one of his most thoughtful and expressive features but also his first original screenplay since 1999’s underrated eXistenZ. Like that film, Crimes of the Future boasts technology that looks constructed from alien bones and tissue, pitting bodily invasions against a tyrannical authority in what amounts to a spy yarn set in a world of conceptual artists. Cronenberg has returned to this narrative model repeatedly since his early career, as seen in Scanners (1981), Videodrome (1983), and Naked Lunch (1991)—not to mention his 63-minute feature from 1970, also called Crimes of the Future, but otherwise unrelated. Originally titled Painkillers and planned for the early 2000s but never produced, Cronenberg unearthed, polished, and retitled the screenplay at a time befitting today’s heightened culture war.

The film’s reputation precedes itself, perhaps as a marketing ploy to ensure this challenging sell reaches the intended horror and art-house crowds. Certainly, Crimes of the Future fulfills the requirements of both niches, offering gooey and freaky images blended with sophisticated existential debates about the evolving relationship between the human body and environmental destruction. Before debuting at the Cannes Film Festival just a few weeks before its US premiere, the director promised walk-outs within the first five minutes. Sure enough, reports that some attendees walked out of Cannes screenings seemed to confirm that Cronenberg had concocted a visceral marathon of body horror to challenge his nastiest efforts on The Brood (1979) or The Fly (1986). But the reality is that Crimes of the Future isn’t the extreme boundary-pushing gauntlet of horrors that some might expect. Although it contains some novel and grisly sights, they serve a meditative film. Cronenberg wields exploitative and provocative imagery to symbolize his ideas through artistic expression—and that’s just what the writer-director’s main characters, performance artist Saul Tenser (Viggo Mortensen) and his personal surgeon-lover Caprice (Léa Seydoux), hope to achieve.

Set in a future of worn concrete and rust, the film unfolds in a perpetual state of elaborate world-building. Yet, Cronenberg resists identifying specific governments or nationalities, lending an allegorical flavor to the proceedings. Human beings like Saul suffer from “Accelerated Evolution Syndrome” and have begun to grow rogue organs. To keep track of them, a National Organ Registry logs new developments with a clunky paper filing system (there’s not a computer or smartphone in sight). Nature has also almost completely muted pain receptors and eliminated infections in humans, making “desktop surgeries” commonplace among the untrained. And, since there’s no risk involved, people have begun exploring the sadomasochistic pleasures and artistic limitations of slicing into the flesh and body modifications—in a numb world, they’re desperate to feel anything. Saul remains one of the few who still feels pain, requiring him to sleep in a bed that shifts to react to his flaring pain centers. A company called LifeForm manufactures the bed, and they also produce Saul’s herky-jerky eating chair—a bony version of Charlie Chaplin’s automated feeding machine in Modern Times (1936). Mortensen’s performance attunes the viewer to his body in every scene, whether in states of pain or pleasure, or in the vampiric black shroud that shields him from allergens. He coughs, hacks, and chokes on his own narrowing throat through discomfited winces and unshakable bodily wrongness. It’s another subtle but brilliantly crafted performance by Mortensen for Cronenberg.

Set in a future of worn concrete and rust, the film unfolds in a perpetual state of elaborate world-building. Yet, Cronenberg resists identifying specific governments or nationalities, lending an allegorical flavor to the proceedings. Human beings like Saul suffer from “Accelerated Evolution Syndrome” and have begun to grow rogue organs. To keep track of them, a National Organ Registry logs new developments with a clunky paper filing system (there’s not a computer or smartphone in sight). Nature has also almost completely muted pain receptors and eliminated infections in humans, making “desktop surgeries” commonplace among the untrained. And, since there’s no risk involved, people have begun exploring the sadomasochistic pleasures and artistic limitations of slicing into the flesh and body modifications—in a numb world, they’re desperate to feel anything. Saul remains one of the few who still feels pain, requiring him to sleep in a bed that shifts to react to his flaring pain centers. A company called LifeForm manufactures the bed, and they also produce Saul’s herky-jerky eating chair—a bony version of Charlie Chaplin’s automated feeding machine in Modern Times (1936). Mortensen’s performance attunes the viewer to his body in every scene, whether in states of pain or pleasure, or in the vampiric black shroud that shields him from allergens. He coughs, hacks, and chokes on his own narrowing throat through discomfited winces and unshakable bodily wrongness. It’s another subtle but brilliantly crafted performance by Mortensen for Cronenberg.

For Saul and Caprice, their artwork represents a reclamation of the body on conscious terms. In their underground avant-garde performances, attendees watch and snap photos as Caprice uses a LifeForm autopsy bed, called a Sark (as in “sarcophagus”), directing scalpel arms to cut into Saul and remove his new organs. Caprice tattooed the new organs—whose purposes remain unknown—and thus replaced their meaning with artistic intent. In a manner not dissimilar to Allegra Geller (Jennifer Jason Leigh), the game designer from eXistenZ who preferred virtual worlds, the characters in Crimes of the Future use the body as an artistic component and medium. This leads to Saul’s invitation to an underground award show, where he’s nominated for Best New Organ in a secret competition arranged by Wippet (Don McKellar) of the National Organ Registry. If Saul and Caprice’s art is “uniquely self-referential” in its physical self-reflexivity, then so is Cronenberg’s. The scenario brings to mind a line from Dead Ringers (1988), where one of the identical twin gynecologists reflects, “I’ve often thought that there should be beauty contests for the insides of bodies.” In another scene, the other brother quips, “Surely you’ve heard of inner beauty.” Both statements apply in this increasingly bizarre world where the internal becomes external.

Of course, Cronenberg doesn’t miss an opportunity to explore his characters’ sexuality in these terms. After all, every artist has groupies. Enter Kristen Stewart as Timlin, a twitchy and mannerist fusspot who becomes fixated on Saul through her work at the National Organ Registry. After watching one of his performances, she whispers to him, “Surgery is the new sex,” and imagines an alternative penetration with the Sark bed. Indeed, the “King of Venereal Horror” remains interested in examining sexuality and orifices with almost clinical fascination—note the clinical kiss between Timlin and Saul. And forget the scar-licking scene in Cronenberg’s Crash (1996); Saul and Caprice’s sex life finds her licking his innards from a gaping incision in his belly while he wryly groans, “Don’t spill.” The difference between Crimes of the Future and Crash, or even a related film such as Julia Ducournau’s Titane (2021), is that Cronenberg manages to evoke some manner of sensuality in his deviant sex scenes thanks to the chemistry between Mortensen and Seydoux. That is, except for a rather cheap moment involving two techs who disrobe in what feels like a needless return to Cronenberg’s exploitative roots.

The film’s political and conspiratorial bent introduces Welket Bungué as a detective who has enlisted Saul to gather information about subversives. Namely, the authorities want to stop Lang Dotrice (Scott Speedman), who heads a group of environmentalist revolutionaries with engineered new organs—an entire digestive system that allows them to consume and process plastic as food, thus “feeding on our own industrial waste” to bring about environmental equilibrium. Lang’s dead son—who was born with this ability and was suffocated by his mother (Lihi Kornowski), who believed him an unnatural abomination in the film’s sharp first scenes—becomes a martyr of Lang’s revolution. Lang convinces Saul and Caprice to perform a live autopsy on the boy’s corpse to bring awareness to his movement and this evolutionary mutation. And in true Cronenberg fashion, keeping track of the motives, double-crosses, and assassinations along the way proves head-spinning. But the resolution settles on a form of acceptance that our bodies change. Depending on your perspective, that change might be progressive or degressive. But the sublime final shot finds Caprice recording Saul in the throes of that change rather than fighting it through their surgical art—an image that finds Mortensen’s perpetually uneasy character relaxing into his naturally mutated state.

The film’s political and conspiratorial bent introduces Welket Bungué as a detective who has enlisted Saul to gather information about subversives. Namely, the authorities want to stop Lang Dotrice (Scott Speedman), who heads a group of environmentalist revolutionaries with engineered new organs—an entire digestive system that allows them to consume and process plastic as food, thus “feeding on our own industrial waste” to bring about environmental equilibrium. Lang’s dead son—who was born with this ability and was suffocated by his mother (Lihi Kornowski), who believed him an unnatural abomination in the film’s sharp first scenes—becomes a martyr of Lang’s revolution. Lang convinces Saul and Caprice to perform a live autopsy on the boy’s corpse to bring awareness to his movement and this evolutionary mutation. And in true Cronenberg fashion, keeping track of the motives, double-crosses, and assassinations along the way proves head-spinning. But the resolution settles on a form of acceptance that our bodies change. Depending on your perspective, that change might be progressive or degressive. But the sublime final shot finds Caprice recording Saul in the throes of that change rather than fighting it through their surgical art—an image that finds Mortensen’s perpetually uneasy character relaxing into his naturally mutated state.

To be sure, Cronenberg mines the natural and unnatural, artistic and political, traditional and unconventional in his chilly and academic style. Crimes of the Future isn’t a film of warm emotions or characters who behave in relatable ways (Seydoux and Stewart have admitted to the press that they didn’t understand the script, but they went with it nonetheless). Much like the director’s Naked Lunch or Cosmopolis (2012), the characters and action here feel symbolic and, therefore, more akin to conceptual art than a traditional science-fiction or horror movie (even so, there’s a curious sentimentality in the all-accepting bond between Saul and Caprice). Cinematographer Douglas Koch (who shot McKellar’s apocalyptic 1998 film, Last Night) captures the drab and stagelike sets created by production designer Carol Spier, presenting scenes that look and play like art installation pieces. Although it bears the hallmarks of a body horror film, Crimes of the Future will resonate more with art film aficionados than horror fans. But this is not to suggest that the film somehow lacks something, only to note Cronenberg’s more theoretical approach.

Crimes of the Future is a statement to receive change as it comes and not fight the inevitable. The film cannot help but feel representative of ideas rooted in a futile culture war in which tradition tries to preserve itself and difference evolves regardless. There’s something beautiful about this idea, the occasionally disturbing nature of Cronenberg’s concepts and visuals notwithstanding. There’s also a certain comic absurdity flowing beneath the material. Audiences might not know if they should laugh, squirm, or sit up and lean in—doubtless, Cronenberg wants all reactions. He wants us to think about our aches and pains, our environments, and how our bodies and self-expression fit into those worlds. Cronenberg, approaching 80 as of this review, almost certainly admires Saul’s ability to continue making art despite his physical woes. Their shared willingness to welcome change and turn those new concepts into art has kept Saul and Caprice vital and alive. Crimes of the Future, then, is a fascinating and inspired look at the transformational reality of the body—an urgent and personal treatise on art that echoes Cronenberg’s twentieth-century work and finds him at his most contemplative and parabolic.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review