Creed III

By Brian Eggert |

Adonis Creed finally emerges from under the shadow of Rocky Balboa in Creed III. While Creed (2015) sought to reinvigorate the Rocky brand with a focus on Apollo Creed’s son, it ultimately followed the so-called requel template, adhering too closely to the Rocky storyline and giving audiences more of the same, only different. A similar problem left Creed II (2018) feeling like a vacuous retread of Rocky IV (1985), complete with the brutish son of Ivan Drago as the opponent, except the story was utterly devoid of personal motivations for the boxers. Both films were underwritten, giving Jordan, an actor of skill and ferocity, little to do. Refreshingly, Creed III corrects the problems of the earlier movies in almost every way. Star Michael B. Jordan makes an impressive directorial debut in the latest, delivering the best Creed yet and a sequel that surpasses most Rocky movies. The script shows an interest in what compels the fighters to enter the ring, establishing a weighty set of personal stakes. The boxing scenes involve more than combatants who pummel each other; rather, they explore boxing strategy and technique. Jordan even turns the final bout into a visualization of Creed’s headspace, marking the most artistically expressive sequence in any Rocky adjacent film. Overall, it’s a thoughtfully written, passionately acted, and thoroughly entertaining boxing picture.

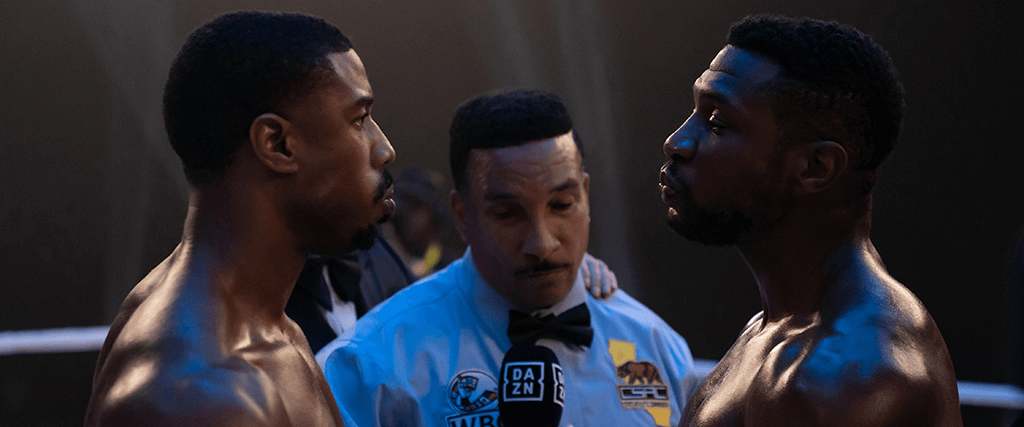

Perhaps the most notable departure in Creed III is the absence of the series creator, Stallone, whose Rocky reconnected with his estranged son at the end of Creed II. Stallone still serves in a producer capacity here, but otherwise, he passes the baton to Jordan. Working from a script by Keenan Coogler and Zach Baylin (with story contributions from Ryan Coogler), Jordan’s film relocates the story from Philadelphia to Los Angeles, the stomping ground of the young Adonis “Donnie” Creed (Alex Henderson). In a series of flashbacks that gradually reveal the complete story over the two-hour runtime, the film explores an incident from Donnie’s adolescence involving an older teen friend, Damian “Dame” Anderson (Spence Moore II). A Golden Glove champ, Dame held promise as a professional boxer and mentored Donnie until an incident set them on divergent paths. In a strain reminiscent of Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), fate sent Dame to prison for 18 years while Donnie became a world-renowned champ. Early in the film, Dame, now played by Jonathan Majors, returns and seeks out his old friend, hoping he can restart his boxing career even though he’s never fought a professional match as an adult.

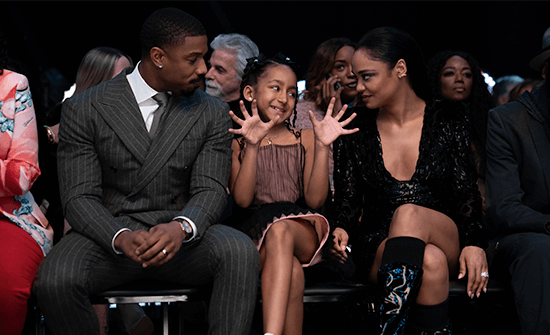

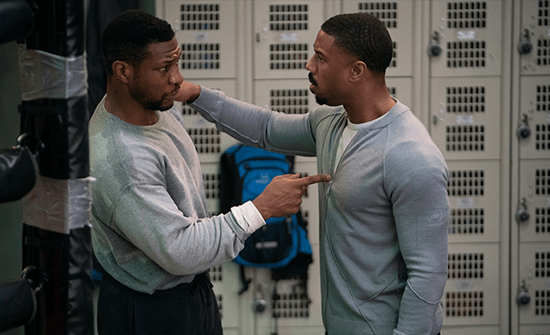

Creed III patiently establishes what develops into a personal conflict between Donnie and Dame. Jordan and his screenwriters correct a weakness from earlier Creed entries by exploring Donnie’s inner life, whereas before, his actions seemed contingent on Rocky. Donnie and Dame’s antagonism builds naturally, with Jordan and Majors evoking evident chemistry and uneasiness that hints at their characters’ unsettled past. Early on, Donnie earns the moniker of world heavyweight champion one last time before retiring into promoter mode. Similarly, due to her progressive hearing loss, his musician wife Bianca (Tessa Thompson) steps back from stage shows and resolves to produce. They live a cushy life with their deaf daughter Amara (Mila Davis-Kent), evidenced by their luxurious mansion and tender scenes of ASL between them. They’re the picture of success. But Dame’s presence at the gym gradually destabilizes Donnie’s work and home life. Dame insists on getting a title shot against Donnie’s star fighter, Felix (Jose Benavidez), who has an upcoming match against Viktor Drago (Florian Munteanu). He also suggests that neither Donnie nor Bianca are as happy as they pretend to be in their current roles, causing friction between the couple.

Creed III patiently establishes what develops into a personal conflict between Donnie and Dame. Jordan and his screenwriters correct a weakness from earlier Creed entries by exploring Donnie’s inner life, whereas before, his actions seemed contingent on Rocky. Donnie and Dame’s antagonism builds naturally, with Jordan and Majors evoking evident chemistry and uneasiness that hints at their characters’ unsettled past. Early on, Donnie earns the moniker of world heavyweight champion one last time before retiring into promoter mode. Similarly, due to her progressive hearing loss, his musician wife Bianca (Tessa Thompson) steps back from stage shows and resolves to produce. They live a cushy life with their deaf daughter Amara (Mila Davis-Kent), evidenced by their luxurious mansion and tender scenes of ASL between them. They’re the picture of success. But Dame’s presence at the gym gradually destabilizes Donnie’s work and home life. Dame insists on getting a title shot against Donnie’s star fighter, Felix (Jose Benavidez), who has an upcoming match against Viktor Drago (Florian Munteanu). He also suggests that neither Donnie nor Bianca are as happy as they pretend to be in their current roles, causing friction between the couple.

Majors is a force of seething energy here, giving an embodied performance as the unpolished and unstable Dame, unlike anything the actor (from Da 5 Bloods to The Harder They Fall) has done before. After convincing Donnie to back him—with the line, “If Apollo Creed can take a chance on some underdog, why can’t you?”—Dame begins promoting his eventual bout against Felix. He appears reserved before cameras, almost stuttery, allowing the actor to convey his most mannerist performance yet. But the character’s performance in the ring suggests to the trainer, Duke (Wood Harris), that Dame is “fighting the world, and he’s trying to hurt people.” It’s a warning Donnie dismisses until Dame sends Felix to the hospital and then sharply turns on his former friend, clearly having schemed for his success. Although Dame begins as the ex-con underdog, the inevitable match between the two childhood friends reframes Donnie as an older, broken-down fighter with physical weaknesses from a career in the ring—an underdog in the sense that he’s past his prime, and Dame knows it.

But before Donnie can think about fighting Dame, he must confront repressed traumas—their troubled upbringing in an abusive group home environment, which Donnie has hidden from Bianca, and Donnie’s guilt over never reaching out during his friend’s prison time. Worse, his mother (Phylicia Rashad) suppressed Dame’s letters from prison, adding to Dame’s sense of betrayal. Whereas these events turned Dame into an embittered rival, they also threaten to eat away at our hero, leaving them with unresolved baggage they can only work out in the ring. This conflict presents a vast improvement over Creed’s forgettable and stake-less opponent and the hulking nonentity from Creed II. Moreover, when the customary training montage arrives courtesy of editors Tyler Nelson and Jessica Baclesse, there’s a sense of progression—the retired fighter must get back in shape and grapple with his psychological hangups. If Dame fights with anger, Donnie must rely on his understanding of focus and timing. But most of all, it’s about Donnie being able to communicate with emotional intelligence to Bianca about a past he tried to forget, giving way to a heartfelt scene between Jordan and Thompson. By extension, a subplot involving Amara’s interest in boxing and a fight at her school frames her as the resident stand-in for The Dead End Kids from Angels with Dirty Faces—her fate is in the hands of whoever wins the final match, Dame or Donnie, anger or control.

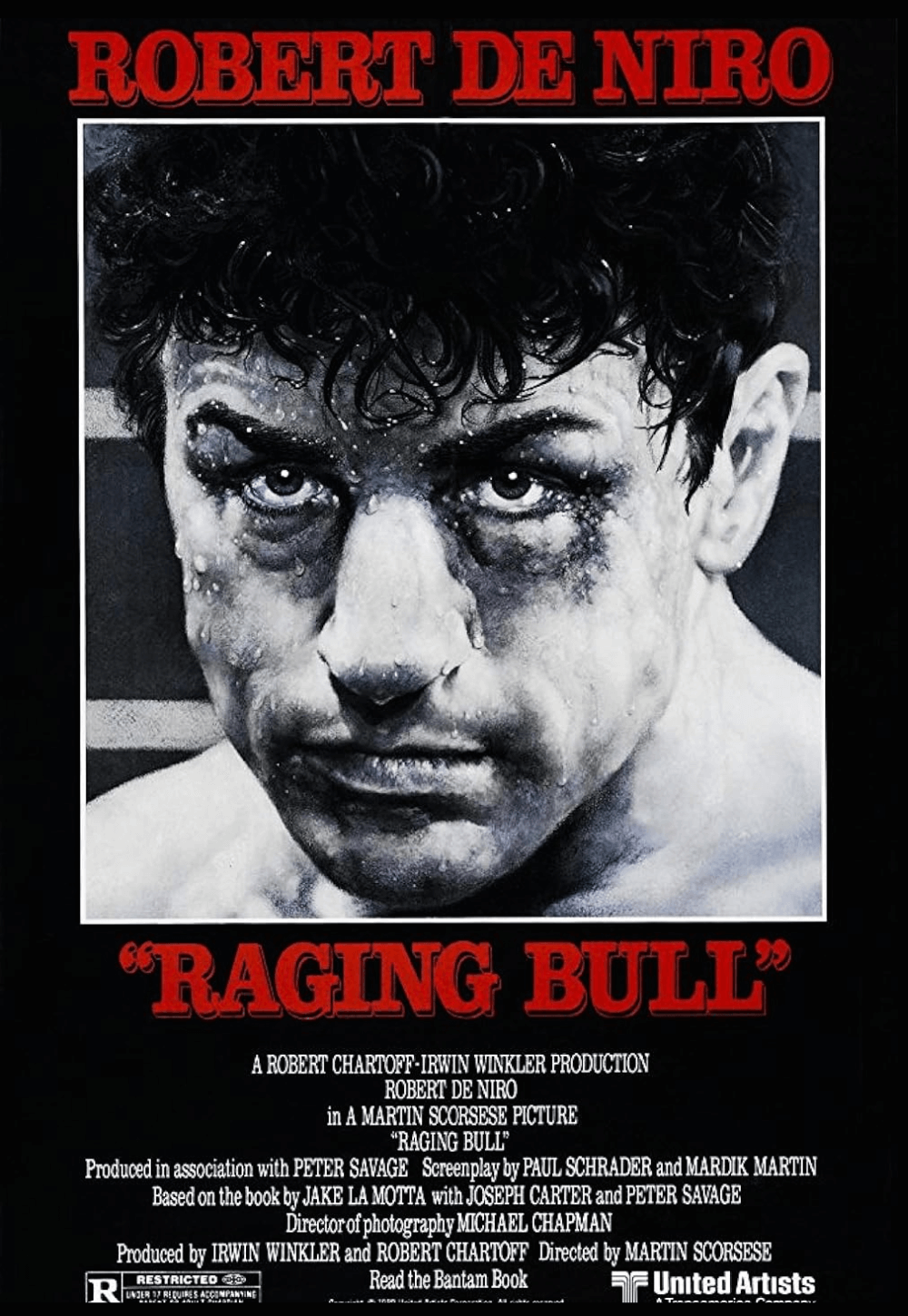

Just as Stallone directed himself in several Rocky sequels, Jordan takes command and improves on the formula in unexpected ways. The first-time director relies too much on CGI auditoriums to capture the vast crowd on fight night, but the fight coordination makes up for the backdrop’s artificiality. Jordan deploys a slow-motion strategy where Duke’s coaching or Creed’s eyes identify weaknesses in the opponent, and the viewer feels involved in moment-by-moment reasoning behind each blow. Whereas most Rocky movies featured unbridled violence without an inkling of technique, Jordan shows an interest in the tactical maneuvers behind the sport. Best of all, when Donnie and Dame reach the emotional zenith of their match, everything else fades away. All at once, fog surrounds the ring, and the screaming fans disappear. The opponents see each other as children, and literal prison bars appear, locking them together in the ring. It’s a flourish that Jordan no doubt borrowed from Raging Bull (1980), and how Martin Scorsese turned the ring into a symbolic evocation of Jake LaMotta’s emotional state. In Jordan’s hands, these poetic touches show Donnie overcoming his mental blocks to focus on what becomes a tense, breathless boxing sequence.

Just as Stallone directed himself in several Rocky sequels, Jordan takes command and improves on the formula in unexpected ways. The first-time director relies too much on CGI auditoriums to capture the vast crowd on fight night, but the fight coordination makes up for the backdrop’s artificiality. Jordan deploys a slow-motion strategy where Duke’s coaching or Creed’s eyes identify weaknesses in the opponent, and the viewer feels involved in moment-by-moment reasoning behind each blow. Whereas most Rocky movies featured unbridled violence without an inkling of technique, Jordan shows an interest in the tactical maneuvers behind the sport. Best of all, when Donnie and Dame reach the emotional zenith of their match, everything else fades away. All at once, fog surrounds the ring, and the screaming fans disappear. The opponents see each other as children, and literal prison bars appear, locking them together in the ring. It’s a flourish that Jordan no doubt borrowed from Raging Bull (1980), and how Martin Scorsese turned the ring into a symbolic evocation of Jake LaMotta’s emotional state. In Jordan’s hands, these poetic touches show Donnie overcoming his mental blocks to focus on what becomes a tense, breathless boxing sequence.

Of course, previous Rocky movies have explored how there’s more for the hero to work through than knocking the other man out. But Jordan weaves this notion into the drama and filmmaking, marking a welcome stylistic divergence from earlier entries in the franchise. It’s this brand of form-follows-function execution that makes Jordan’s first round as director so accomplished. Some may consider the proceedings far too expressive for the usually gritty and grounded Rocky movies, which appropriately echoed their unassuming hero. But Adonis Creed is another kind of character, and he demands another type of movie. Jordan also gives one of his best performances in the role, lending the character dimensions that earlier iterations ignored. He does the character justice by eschewing elements of what came before and making the character his own. Majors, it must be said, enhances the movie with an urgently dangerous yet ultimately sympathetic rival. As a result, Creed III earns a place among the best boxing movies for expressing that the ring is more than a modern-day gladiatorial arena but, in cinema, a reflection of the interior lives of those inside it.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review