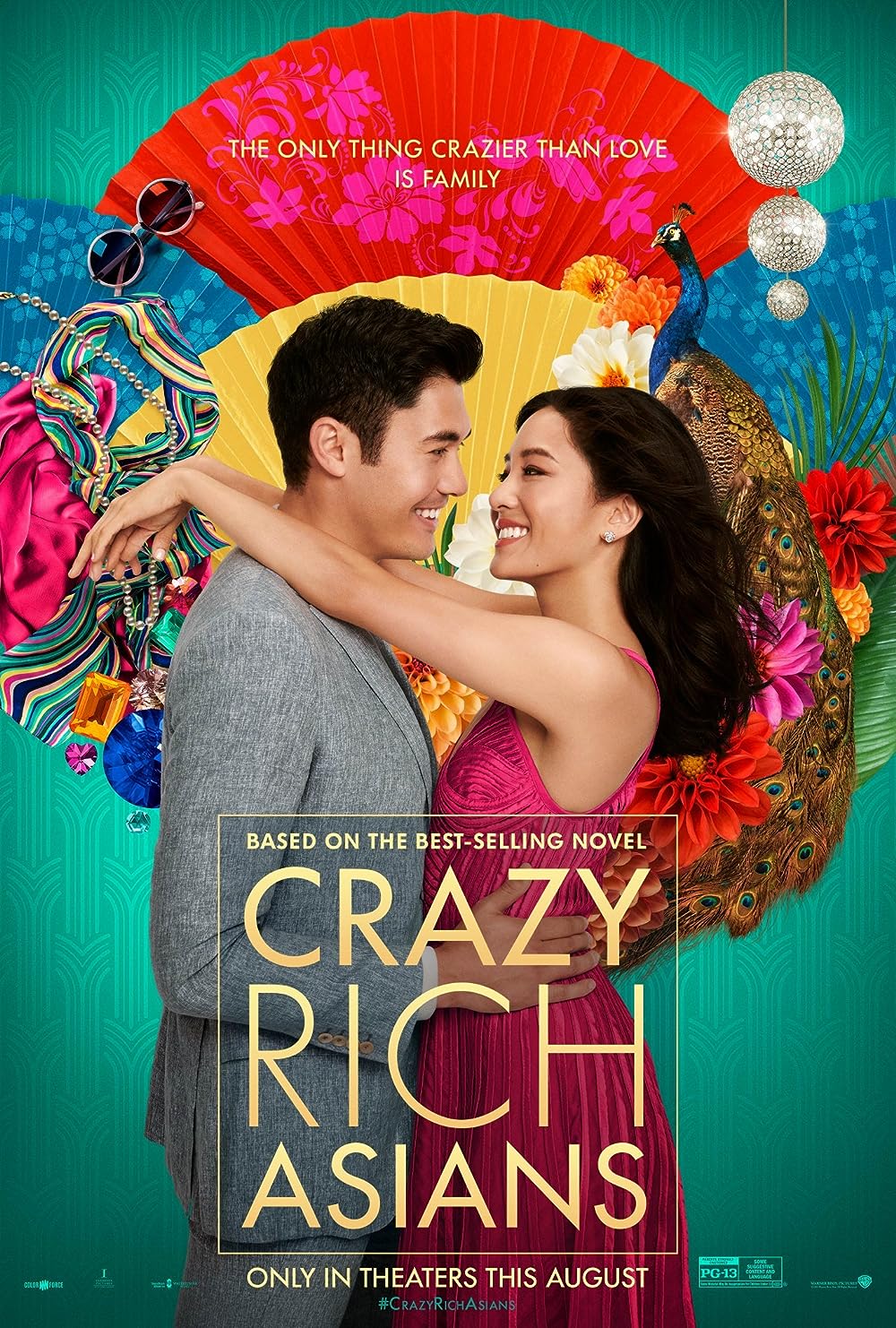

Crazy Rich Asians

By Brian Eggert |

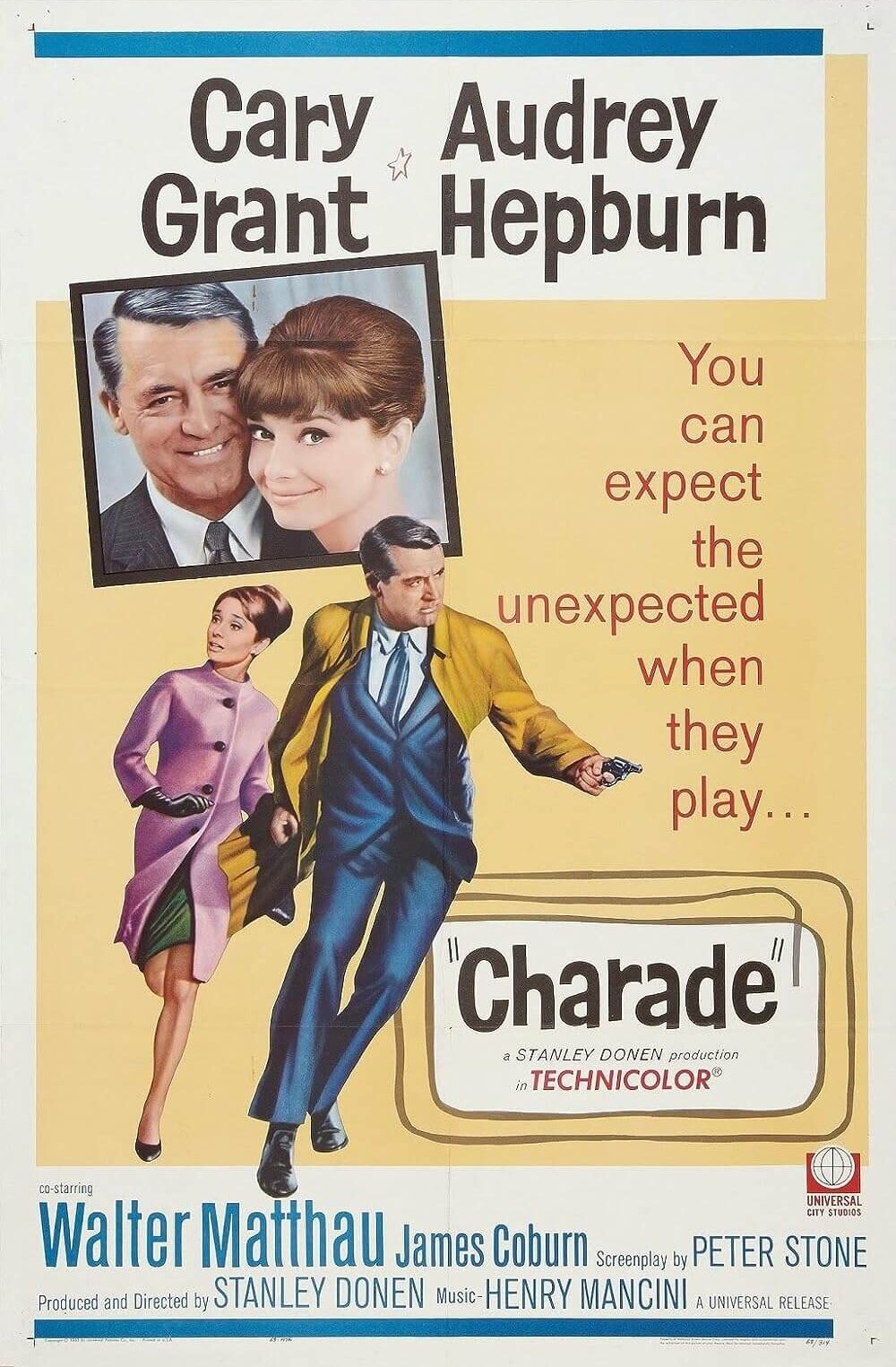

A great romantic comedy is rare. Years can pass without a worthwhile or even memorable romantic comedy hitting theaters. In recent memory, one must go back to 2013 for either Nicole Holofcener’s Enough Said or Joss Whedon’s black-and-white adaptation of Much Ado About Nothing. The Shakespeare play of the latter was arguably the first rom-com in the history of fiction, while Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night from 1934 established an essential cinematic template for the genre: an admirer pines for the affection of someone out of their class, and the culture clash between them becomes the trouble for the two would-be lovers to overcome. Such is the formula for many of the most beloved rom-coms: The Lady Eve (1940), Roman Holiday (1953), Sabrina (1954), The Princess Bride (1987), Clueless (1995), and countless others. Using this familiar outline, Crazy Rich Asians, based on the 2013 novel by Kevin Kwan, becomes that seldom experienced rom-com that proves crowd-pleasing and accessible without demeaning itself; rather, it elevates the familiar narrative trajectory with some added extratextual import.

Rarer still than great romantic comedies are Hollywood productions with predominantly Asian cast members. After The Joy Luck Club and Ang Lee’s The Wedding Banquet, both released in 1993, nothing even comes close to such lighter fare in terms of representation. Kundun (1997), Memoirs of a Geisha (2005), and Letters from Iwo Jima (2006) might prove to be exceptions, but they were based on established, commercially viable literary sources and intended to receive awards consideration, similar to The Last Emperor (1987)—not exactly mainstream subject matter that will connect with the average moviegoer. Backed by Warner Bros. on the strength of Kwan’s bestseller and, given its two sequels, the potential of a trilogy should the film perform well, Crazy Rich Asians tackles Asian and Asian-American identity in a way that viewers never get to see. Much is riding on the success of the film, including the future of Asian-led stories on American screens. Fortunately, this is an exuberant, spirited pleasure that is bound to connect with a lot of people in a unique way.

In an amusing prologue set at a high-class London hotel in the 1990s, a rain-drenched Eleanor Young (the excellent Michelle Yeoh), accompanied by her two young children, attempts to confirm her reservation. The snooty hotel manager, one of the only white people to appear in the film, turns down her reservation and suggests she try “Chinatown” instead. A moment later, he eats his words when he learns that Mrs. Young belongs to one of the wealthiest families in the world, and her husband has just acquired the exclusive hotel. The scene defies the Western prejudice that Asians do not live by capitalistic drives, and then proceeds to introduce us to a world of extreme opulence and garish ornamentation—affecting the same rather guilty appeal as reality television shows about the lifestyles of the freakishly wealthy. At the same time, Crazy Rich Asians is a fairy tale love story with a surprisingly insightful look at class and cultural difference.

The plot follows Rachel Chu (Constance Wu, in a charming and layered performance), a middle-class Chinese-American professor of economics at NYU. She’s blissfully unaware that her boyfriend, Nick Young (Henry Golding), belongs to Singapore’s most ridiculously, disgustingly rich family. Only when she travels with Nick to Singapore to attend the wedding of his best friend, Colin (Chris Pang), does she realize the extent of his wealth, but also the stringent familial and social order to which he belongs. Nick is heir to a dynasty of old money with its hands in everything from real estate to banking, and with that comes a responsibility to tow the family line. This means a mild-mannered girl from New York, despite her Chinese heritage, is nothing more than an American foreigner to the Singapore-based family, led by Nick’s domineering and well-educated mother, Eleanor, and his seemingly kindly grandmother (the legendary Lisa Lu).

The plot follows Rachel Chu (Constance Wu, in a charming and layered performance), a middle-class Chinese-American professor of economics at NYU. She’s blissfully unaware that her boyfriend, Nick Young (Henry Golding), belongs to Singapore’s most ridiculously, disgustingly rich family. Only when she travels with Nick to Singapore to attend the wedding of his best friend, Colin (Chris Pang), does she realize the extent of his wealth, but also the stringent familial and social order to which he belongs. Nick is heir to a dynasty of old money with its hands in everything from real estate to banking, and with that comes a responsibility to tow the family line. This means a mild-mannered girl from New York, despite her Chinese heritage, is nothing more than an American foreigner to the Singapore-based family, led by Nick’s domineering and well-educated mother, Eleanor, and his seemingly kindly grandmother (the legendary Lisa Lu).

Thrust into the impossibly extravagant and not always tasteful surroundings of Singapore’s elite and elitist class, Rachel finds herself among gossiping mean girls, sometimes cruel women who think she’s a gold digger, and scheming matriarchs. It takes the support and explanation of her old college pal, Peik Lin (Awkwafina, idiosyncratic as ever), who lives in a house that her weirdo family modeled after Versailles, before Rachel finally realizes her situation. In some ways, the naïve heroine has been dropped into a nest of vipers, by no fault of Nick’s. Although, not everyone proves so cruel and judgmental of her “commoner” class. Rachel finds a sympathetic shoulder in Astrid (Gemma Chan), Nick’s elegant cousin with her own romantic problems, as well as the high-couture-obsessed Oliver (Nico Santos), another cousin. Meanwhile, unlikely director Jon M. Chu, whose previous work includes blockbuster sequels like G.I. Joe: Retaliation and Now You See Me 2, captures the dizzying, gold-plated excess in fluid camerawork, including a lavish reception atop the Marina Bay Sands hotel and the futuristic-looking Gardens by the Bay nearby.

Of course, if Hollywood were a just and fair place, Crazy Rich Asians wouldn’t seem overdue, and the last year or two wouldn’t seem so exceptional for their diversity. Films like Get Out, Coco, Hidden Figures, Black Panther, Sorry to Bother You, Blindspotting, and BlacKkKlansman have represented distinct cultures in ways that have reached larger audiences than they might have in previous years. That representations of non-white characters feel like a breakthrough is an unfortunate reality that, in time perhaps, will stop feeling like such a victory. With that in mind, Crazy Rich Asians is not meant to be all things for all people of Asian and Asian-American cultures. It’s simply a step—hopefully not the first—in the right direction, and hopefully, it will mean more Asian faces and stories on the screens of multiplexes around the world.

Industry relevancies asides, this is a joyous, satisfying film, and a class melodrama in the best sense. It’s the sort of romantic comedy that hits every beat it means to, without ever feeling overly manipulative or cynically devoted to a formula. Best of all, when Eleanor demonstrates how jealously loyal to preserving tradition she can be, the film avoids turning her into a villain—instead, it seeks to understand why, in Singapore culture, she values legacy over Rachel’s decidedly American notion of personal ambition. Crazy Rich Asians resists one-dimensional characters and, further, yearns for the understanding of complex cultural demands—a diplomatic idea, to be sure. Still, the film doesn’t skimp on the basic rom-com pleasures, or the eventual swell of happy tears as Rachel and Nick solidify their love in spite of the family pressures. Audiences versed in the genre will recognize the predictable journey of the story, but the colorful environments, unapologetic displays of luxuriance, moments of passion, and constant laughs make Crazy Rich Asians unquestionable fun, and a romantic comedy to remember.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review