Cosmopolis

By Brian Eggert |

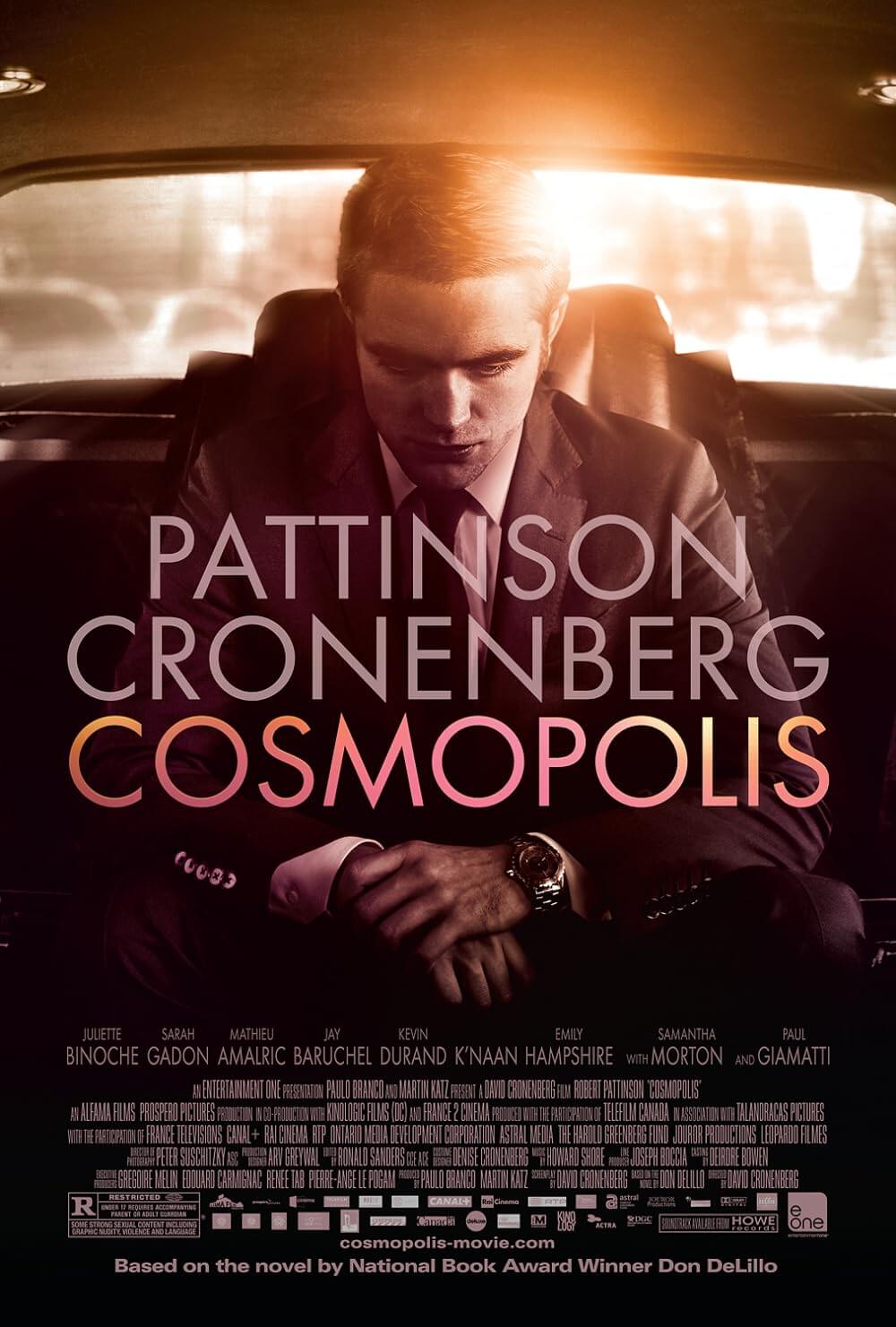

David Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis is a film for which a plot summary can be provided, but no matter how detailed, a description of the events alone will not explain what this ornate allegory is about, nor will a single viewing. Based on and closely following the 2003 novel by Don DeLillo, Cronenberg’s first screenplay since 1999’s eXistenZ proceeds with characteristic intelligence and other-worldliness. Herein, Robert Pattison plays billionaire cyber-capitalist Eric Packer, whose day-long trip from one end of a dystopian Manhattan to the other in his stretch limo commences because he wants a haircut. Along the way, he conducts a series of episodic, detached business and personal meetings with associates and friends, and all the while teems on his throne with a yearning for self-destruction. And at first glance, the film might seem to be just about the consequences of capitalist excess, but Cronenberg’s picture is far more involved than a mere pro-Occupy argument; as capitalism strips away a person’s humanity, there’s a deeper, all-encompassing despair and irrationality that affects more than just the top 1 percent’s ability to relate to others.

Defined in the opening title sequence created by visual artist Justin Stephenson, which gradually splatters a Jackson Pollack-esque canvas into an image that might be called a futuristic cityscape, the picture shares a kinship with Abstract Expressionist painters in both method and direct reference. When Packer meets with his technology advisor (Jay Baruchel) and currency analyst (Philip Nozuka), they talk about their particular fields with affection, as if tracking pure creation. Packer seems less capable in this respect; specifically, it is the unique, almost artistic flourishes of the Chinese yuan that elude him and ultimately lead to his financial devastation. His conceit is that he believes his money and status and whiz-kid intellect will save him, while another part of him understands that his inflated ego fails to grasp the purity of creation found in Abstract Expressionism, a movement he adores but doesn’t seem to understand. Buying not one but a gallery of works by Mark Rothko, whose art inspired the end credits sequence, becomes a key moment informing Packer.

With his empire crumbling all around him, Packer is constantly warned by his top security man (Kevin Durand) that their trip will be delayed by a presidential motorcade and funeral reception for a famous rapper, but Packer demands they proceed anyway, his itching desire to act irrationally taking over. They progress at a bumper-to-bumper crawl, as outside a rat-themed anti-capitalist movement riots in the streets. Threats received by Packer’s company on his life come from some solitary would-be assassin (Paul Giamatti), who finally arrives late in the film to present an antithetical nemesis not incapable of carrying on a lengthy discussion about where they ideologically diverge. And in spite of the story being about Packer traveling from Point A to Point B, its finer implications are not so clearly defined. Cronenberg demolishes the narrative plane altogether, and a series of encounters unfold, like a gallery of individual paintings, each important on their own and yet of more consequence when seen as an entire gallery.

In these intervallic exchanges, characters speak in a baroque, opaque shorthand that seems to have progressed from a need for extreme isolation, which their tremendous wealth can afford. No longer do they relate to one another in rational or especially emotional conversations; their discourse consists of the philosophical, while their bodies alone engage in the Now. With all kinds of Freudian implications, the director of A Dangerous Method carries out a scene in which Packer receives a prostate exam in the back of his limo; with a doctor fidgeting around back there, Packer makes a pass at his finance manager (Emily Hampshire). His sexual encounters are frequent and unemotional, and periodically he stops for a meal or a chat with his icy wife (Sarah Gordon), a billionaire heiress. All at once, the odyssey’s momentum takes a curious turn when Mathieu Amalric’s pastry assassin arrives and strikes Eric in the face with a slapstick pie, announcing, “I am the action painter of the cream pie!” Strangely, he seems to be the only sane character in the film. To be sure, there’s an almost comic sensibility about the extreme detachment in Cosmopolis.

In these intervallic exchanges, characters speak in a baroque, opaque shorthand that seems to have progressed from a need for extreme isolation, which their tremendous wealth can afford. No longer do they relate to one another in rational or especially emotional conversations; their discourse consists of the philosophical, while their bodies alone engage in the Now. With all kinds of Freudian implications, the director of A Dangerous Method carries out a scene in which Packer receives a prostate exam in the back of his limo; with a doctor fidgeting around back there, Packer makes a pass at his finance manager (Emily Hampshire). His sexual encounters are frequent and unemotional, and periodically he stops for a meal or a chat with his icy wife (Sarah Gordon), a billionaire heiress. All at once, the odyssey’s momentum takes a curious turn when Mathieu Amalric’s pastry assassin arrives and strikes Eric in the face with a slapstick pie, announcing, “I am the action painter of the cream pie!” Strangely, he seems to be the only sane character in the film. To be sure, there’s an almost comic sensibility about the extreme detachment in Cosmopolis.

As a result, Pattison’s raw and coldly charismatic qualities turn this into his best and most substantial role. And yet, the Twilight star, teen heartthrob, and tabloid cover-boy seems curiously out of place in Cronenberg’s oeuvre, although one cannot help but feel the Canadian director has used Pattison’s fame to his film’s advantage, though not only for the obvious commercial upside. In an age where teen Twi-hards might seek out the latest Cronenberg film because of Pattison’s presence, this trend helps Cosmopolis make its point as much as Pattison’s unavoidable draw contradicts it. In one way, Cronenberg employs Pattison as a device to bait audiences into seeing his film, in turn resulting in a financial success for this $20 million budgeted picture; in another way, he forces that unlikely audience into an intellectual discussion about the self-destructive nature of capitalism, fame, technology, and isolation. These opposing uses for Pattinson never work themselves out on or off-screen, but they never fall as low as the grand philosophical contradiction made by other films with similar motives. Fight Club, for example, is an anti-conformity film in which Brad Pitt, of all people, critiques the mainstream and ultimately turns an otherwise rebellious film into a pop-culture phenomenon.

But there’s nothing easily consumable or fashionable about Cosmopolis. This will not become a box-office smash whose posters adorn the walls of teen girls. Mainstream viewers will be lost in the long, dense stretches of dialogue laden with metaphors and epigrams, discussions about existential pessimism, and the intentional artificiality of Packers’ conversations about sexuality and meaningful relationships. When a protracted debate about whether or not Eric can buy Rothko’s Chapel and have it moved into his apartment plays out with his art-dealer-and-lover (Juliette Binoche), there’s a certain audience that will “get” the clever meaning behind this, and others who will feel left out of the punch line. Then again, almost every scene contains this kind of dimension, with topics ranging from money trading to the primal nature of sexual desire, from alienation to the acceptance and denial of the human body in all its beautiful flaws. At the same time, the dialogue itself is spoken with a kind of detached and metonymic quality that enhances the picture’s futurist roots.

On a purely technical plane, Cronenberg employs several of his reliable go-to crew to achieve his signature look and feel. Cinematographer Peter Suschitzky makes the confines of Eric’s limo seem vast yet claustrophobic, with the Toronto-as-Manhattan exteriors sometimes feeling miles away, thus effectively aligning the audience with Eric’s narrow worldview. The antiseptic editing by Ronald Sanders pays careful attention to hands as they reach for a seemingly inconsequential object, instilling our interest in basic gestures. Howard Shore’s almost nonexistent score recedes to the dialogue, which is its own sort of music and is present mostly in brooding tones. Cronenberg’s usual production designer Carol Spier was not available, but Arvinder Grewal brings the same level of almost artificial, stagelike detail: just as in eXistenZ when the main characters stop at a place labeled “Country Gas Station,” here Packer’s wife catches an off-Broadway production called “Stage Play.” Wry little details like this transform Cosmopolis into a film of largely symbolic ideas presented in a figurative visual language.

On a purely technical plane, Cronenberg employs several of his reliable go-to crew to achieve his signature look and feel. Cinematographer Peter Suschitzky makes the confines of Eric’s limo seem vast yet claustrophobic, with the Toronto-as-Manhattan exteriors sometimes feeling miles away, thus effectively aligning the audience with Eric’s narrow worldview. The antiseptic editing by Ronald Sanders pays careful attention to hands as they reach for a seemingly inconsequential object, instilling our interest in basic gestures. Howard Shore’s almost nonexistent score recedes to the dialogue, which is its own sort of music and is present mostly in brooding tones. Cronenberg’s usual production designer Carol Spier was not available, but Arvinder Grewal brings the same level of almost artificial, stagelike detail: just as in eXistenZ when the main characters stop at a place labeled “Country Gas Station,” here Packer’s wife catches an off-Broadway production called “Stage Play.” Wry little details like this transform Cosmopolis into a film of largely symbolic ideas presented in a figurative visual language.

There is a certain elusive mannerism and striving genius behind Cosmopolis that reminds one of Cronenberg’s Crash, another film that incites a profound sense of dread in this critic’s star rating system, because how does one quantify a film like this? No picture this complex, provocative, and so confidently made deserves any kind of negative rating. However, to reduce the film to an arbitrary X-number of stars is like walking through an art museum, glancing briefly at each piece, and when you’ve glimpsed everything, you say that you’ve seen it all. What a narrow view! Cronenberg has created another in a long line of intellectual works, this one bordering on impenetrable. Seeing it once will not be enough, and doubtless, the next time I sit down to watch it (and there will be a next time, and a next time; it’s too intriguing to watch just once), my opinion will change and grow. Then again, some audiences will watch Cosmopolis and feel nothing except indifference. These are the same viewers who rush through fine art museums and, when done, check it off their to-do list. Cronenberg has not made a commercial piece of cinema overly concerned with making money here; this is a work of art whose brushstrokes are masterfully crafted, intricate, sometimes distancing, and nothing short of fascinating.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review