The Definitives

Contagion

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Sitting in the movie theater and watching Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion on opening day, I remember my awareness of the people in the seats and rows around me heightening throughout. A few rows back, a woman sneezed into her hands; then, I noticed her reach for another mouthful of popcorn. An older man down the row hacked a fluid-rich cough, barely covering his mouth. Another person sniffled and wiped their nose on their sleeve. All at once, the whole theater seemed to be crawling with disease. Their symptoms may have been seasonal allergies, but it didn’t matter; I wanted to get out, desperately. The feeling only worsened once the film ended, and I started to leave the theater. Following a crowd of unnerved moviegoers out of the auditorium, I realized that many of those spectators who had been coughing and sneezing had now touched the handrails down the stairs and pushed the theater’s doors open, effectively spreading whatever they had to anyone behind them. At that moment, I couldn’t imagine touching anything in the cinema, much less using the restroom. I wanted nothing except to go home, take a scalding hot shower, and slowly spell out “q-u-a-r-a-n-t-i-n-e” like young Howard Hughes in Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator (2004), until my germ-ridden dread had passed. That’s how one begins to feel after only a few minutes into Soderbergh’s masterful film, whose prescience no one in that theater in 2011 could have possibly imagined.

But Soderbergh and his screenwriter, Scott Z. Burns, probably weren’t too surprised by the pandemic that emerged less than a decade later, which had eerie parallels to their film. The director and screenwriter consulted several specialists in the field to portray realistic events that might occur in a hypothetical scenario. Among them were Dr. W. Ian Lipkin, an epidemiologist from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health; Dr. Larry Brilliant, an epidemiologist who worked with the World Health Organization (WHO) to eliminate smallpox; and Laurie Garrett, a science journalist who has written extensively about plagues and outbreaks, including Ebola. Burns explained to the Chicago Tribune that these experts had all told him the same thing about a virus like the one conceived for Contagion: “This is not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when.” Sure enough, the first signs of a similar viral outbreak appeared in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, with the emergence of a new coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2, dubbed coronavirus disease 2019, now widely known as COVID-19. By March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic. The first thing I, and many others, thought to do was revisit Contagion, and the similarities were staggering.

Contagion was Burns’ second screenplay for Soderbergh after the lysine price-fixing comedy The Informant! (2009). The duo next sought to capture a sprawling international account of a viral pandemic delivered through efficient, multifaceted storytelling—not unlike what Soderbergh’s Traffic (2000) did for the so-called war on drugs. Burns had long been fascinated by the response to diseases and wanted to explore the secondary effects of a global outbreak on society. His script tracks the aggressive virus from an early exposure to its growth into a worldwide pandemic, basing the film’s pathogen—dubbed meningoen cephalitic virus one, or MEV-1—on the real-life Hendra and Nipah viruses, which originate in bats found in Southeast Asia and Australia, and according to the Centers of Disease Control (CDC), travel to humans via horses and pigs. The film supplies a scientifically informed scenario that imparts accurate information to spectators about how diseases spread and the systemic procedures to contain them. It also examines the human response that, depending on the individual, ranges from self-preservation mode to selflessness to exploitation for personal gain. Institutionally, the film shows state borders closed, hospitals overrun, nurses striking, grocery store shelves bare, sanitation abandoned, and Homeland Security wondering if it’s a bio-weapon. But as one character notes, “Someone doesn’t have to weaponize the bird flu. The birds are already doing that.”

Burns and Soderbergh perfected the script over 30 drafts, refining characters, simplifying plotlines, and ensuring scientific accuracy with their consultants. Dr. Lipkin told the Washington Post that he and the other consultants “designed a plausible virus and showed an accurate laboratory and public-health response scenario. I coached the actors how to demonstrate symptoms of the disease. The habitat-destruction scene at the end of the film is a powerful reminder of the zoonotic [animal-to-human] origin of many emerging infectious diseases.” Global Health writer Arthy Santhakumar estimates that “nearly 75 percent of all newly identified human diseases since 1945” are those such as SARS, the bird flu (H5N1), and swine flu (H1N1), which originate from animals. Given the reveal in the final frames of Contagion, the film addresses humanity’s susceptibility to such diseases through heightened contact between humans and animals due to increasing human populations, globalization, deforestation, urban development, and disruption of natural wildlife habitats—all of which increase the likelihood of a novel animal-centric virus leaping the species barrier. Besides charting how diseases of animal origin spread across the globe with humans, the film also portrays that the effort required to engineer a vaccine, secure government approval, and manufacture mass quantities is a slow process that takes many months or more.

Burns and Soderbergh perfected the script over 30 drafts, refining characters, simplifying plotlines, and ensuring scientific accuracy with their consultants. Dr. Lipkin told the Washington Post that he and the other consultants “designed a plausible virus and showed an accurate laboratory and public-health response scenario. I coached the actors how to demonstrate symptoms of the disease. The habitat-destruction scene at the end of the film is a powerful reminder of the zoonotic [animal-to-human] origin of many emerging infectious diseases.” Global Health writer Arthy Santhakumar estimates that “nearly 75 percent of all newly identified human diseases since 1945” are those such as SARS, the bird flu (H5N1), and swine flu (H1N1), which originate from animals. Given the reveal in the final frames of Contagion, the film addresses humanity’s susceptibility to such diseases through heightened contact between humans and animals due to increasing human populations, globalization, deforestation, urban development, and disruption of natural wildlife habitats—all of which increase the likelihood of a novel animal-centric virus leaping the species barrier. Besides charting how diseases of animal origin spread across the globe with humans, the film also portrays that the effort required to engineer a vaccine, secure government approval, and manufacture mass quantities is a slow process that takes many months or more.

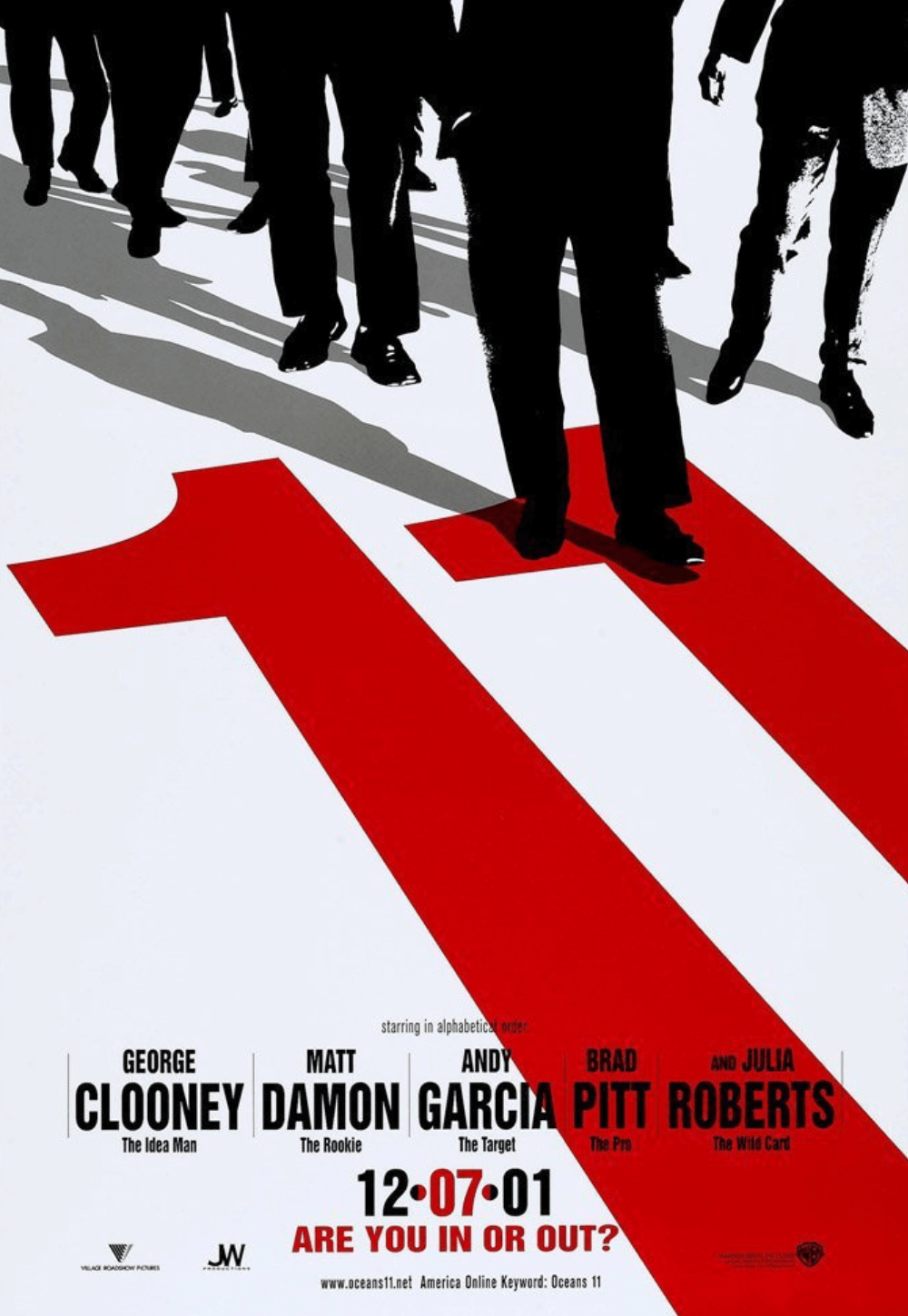

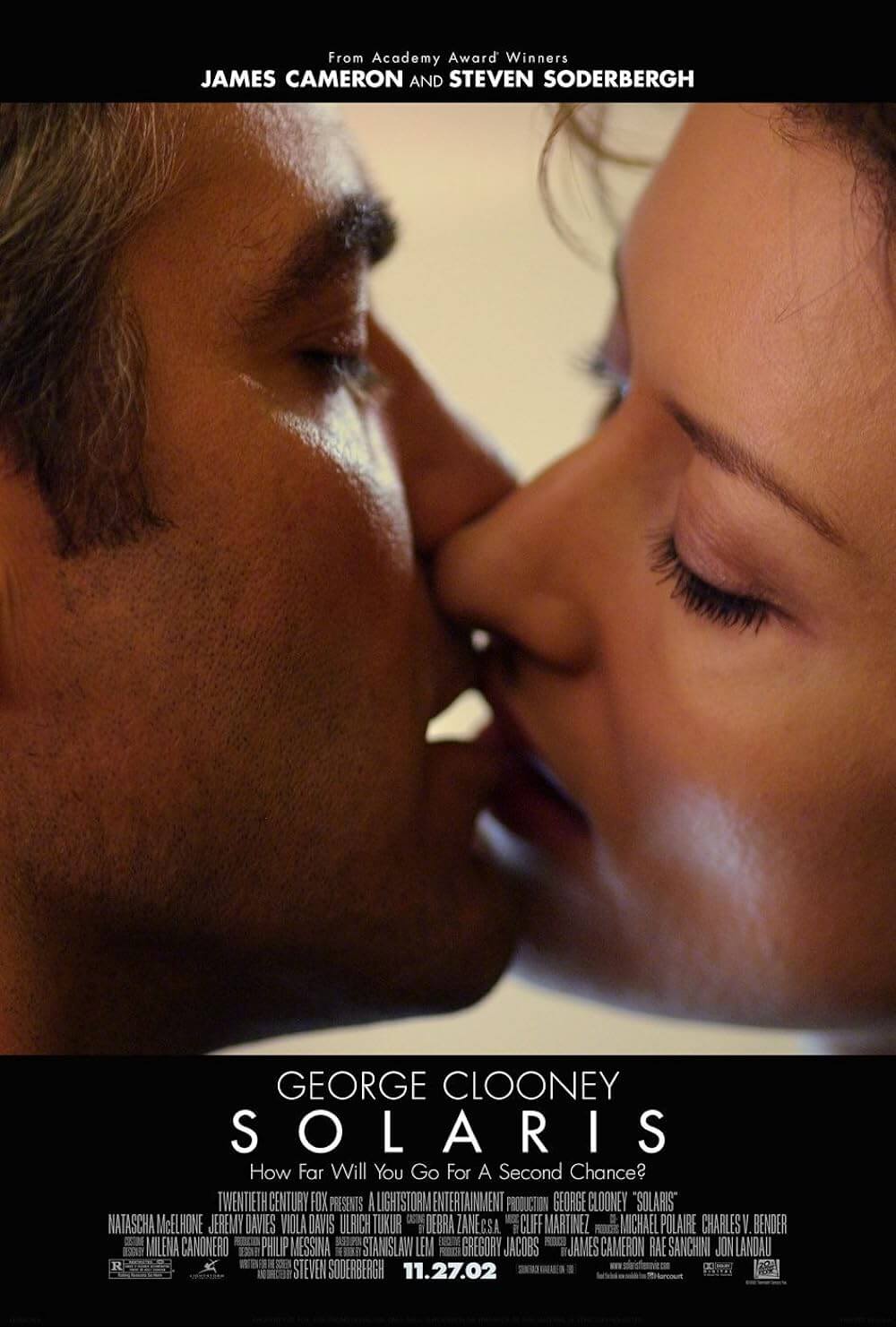

For all its scientific grounding, Soderbergh and Burns modeled Contagion after blockbuster Hollywood entertainments—massive, star-studded Irwin Allen productions from the 1970s, such as The Poseidon Adventure (1972), The Towering Inferno (1974), and The Swarm (1978). Just as Allen’s films once did, Soderbergh negotiates a catastrophe with a distinct brand of mosaic or hyperlink cinema, wherein the audience follows not a single protagonist but an ensemble, consisting of characters who represent key elements in a larger scenario, and then places some of Hollywood’s top performers in those roles. For Contagion, Soderbergh’s approach to narrative occupies a distinct structure, what scholar Wendy Everett calls “fractal,” where multi-strand stories link characters together by unpredictable intersections, with examples ranging from Robert Altman’s Nashville (1975) and Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Babel (2006). Fortunately, Soderbergh’s career resides at the intersection of Hollywood commercialism and art cinema, a rare space in which he demonstrates considerable formal and thematic authorial control by regularly serving as cinematographer and editor, while he also plays the game by appealing to audiences with notable stars. He not only can secure bankable actors for his productions but he often convinces them to work for reduced salaries or even at scale (the lowest amount required by the Screen Actors Guild) as well, assuring his productions remain profitable and that he can continue to work with creative freedom. His Ocean’s trilogy, for instance, has earned Warner Bros. more than a billion dollars in revenue, while many of the director’s smaller projects have failed to turn a profit.

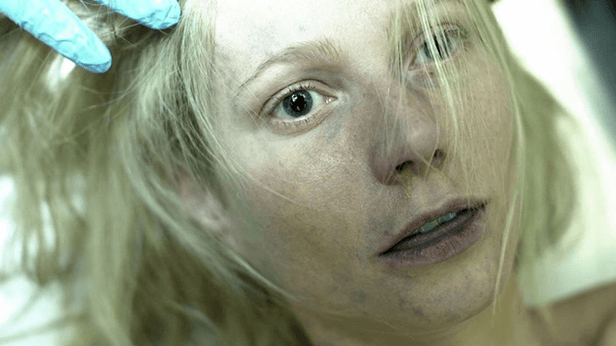

Soderbergh’s careful negotiation of art and commerce often raises questions about his auteur status, which has led scholars Andrew deWaard and R. Colin Tait to declare Soderbergh a “sellebrity” who maintains a “consideration of commerce, promotion, and celebrity into conventional theories of authorship.” Much like Irwin Allen’s productions, Soderbergh casts an impressive roster of celebrities for Contagion, allowing each performer to develop a character with a few precise scenes. Their presence—including Matt Damon, Kate Winslet, Marion Cotillard, Jude Law, Gwyneth Paltrow, Laurence Fishburne, Bryan Cranston, Jennifer Ehle, Sanaa Lathan, Elliot Gould, and John Hawkes—helped justify the production’s $60 million budget, one of the director’s largest. Given the considerable ensemble, Contagion’s characters rarely prove more than two-dimensional, but the performers lend credibility to their roles, and the perambulating story is more substantial than any one performance. Since his commercial breakthrough year in 2000 with Erin Brockovich and Traffic—when Julia Roberts won an Oscar for Best Actress for the former, and Soderbergh won the Best Director award for the latter—Soderbergh has wielded celebrity power to attract audiences to his productions, maximizing the revenue potential for his films. But Soderbergh also harnesses their celebrity to play a subversive trick. Akin to Allen’s disaster movies, no one is safe in Soderbergh’s film, no matter how famous. This is evidenced in a shocking cut early on that finds Gwyneth Paltrow’s Beth Emhoff on the autopsy table, the flap of her scalp skin flopped onto her face as doctors saw into her skull, revealing the infection in her brain.

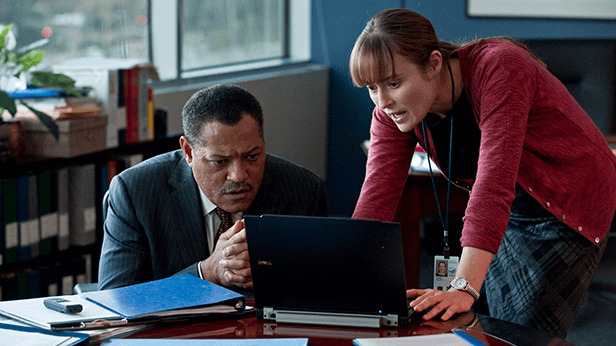

Contagion begins with an accumulation of small, alarming episodes that build unbearable tension: Paltrow returns home to Minneapolis from a business trip in Hong Kong, seemingly jet-lagged; her condition worsens, and she dies from a mysterious disease. Her young boy soon follows, leaving her husband Mitch (Damon) and his daughter from another marriage, Jory (Anna Jacoby-Heron), alone, facing mandated quarantine. More cases break out around the world. Fishburne plays a CDC honcho, Dr. Ellis Cheever, and Cranston is his Homeland Security counterpart. They mobilize resources to contain the spread. Dr. Cheever sends Winslet’s Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer, Dr. Erin Mears, to Minneapolis to control the outbreak there, and she confirms the disease’s incredible ability to find hosts, incubate, and kill at a rate faster than most. As the number of infected reaches millions, Ehle’s lab doctor, Dr. Ally Hextall, takes risky measures to ensure a vaccine is discovered in time, with remote help from Dr. Ian Sussman (Gould). Representing WHO, Dr. Leonora Orantes (Cotillard) attempts to track the “index case” in Hong Kong, but she finds herself held captive until a government official, Sun Feng (Chin Han), secures vaccines for his village. All the while, online personality Alan Krumwiede (Law) spreads profitable fear and misinformation with his bogus conspiracy theories, claiming to have a homeopathic cure made from the flowering forsythia plant. Meanwhile, looting and violence follow widespread terror as the CDC promotes social distancing and state governments shut down borders until they can distribute a vaccine via a lottery system.

Contagion begins with an accumulation of small, alarming episodes that build unbearable tension: Paltrow returns home to Minneapolis from a business trip in Hong Kong, seemingly jet-lagged; her condition worsens, and she dies from a mysterious disease. Her young boy soon follows, leaving her husband Mitch (Damon) and his daughter from another marriage, Jory (Anna Jacoby-Heron), alone, facing mandated quarantine. More cases break out around the world. Fishburne plays a CDC honcho, Dr. Ellis Cheever, and Cranston is his Homeland Security counterpart. They mobilize resources to contain the spread. Dr. Cheever sends Winslet’s Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer, Dr. Erin Mears, to Minneapolis to control the outbreak there, and she confirms the disease’s incredible ability to find hosts, incubate, and kill at a rate faster than most. As the number of infected reaches millions, Ehle’s lab doctor, Dr. Ally Hextall, takes risky measures to ensure a vaccine is discovered in time, with remote help from Dr. Ian Sussman (Gould). Representing WHO, Dr. Leonora Orantes (Cotillard) attempts to track the “index case” in Hong Kong, but she finds herself held captive until a government official, Sun Feng (Chin Han), secures vaccines for his village. All the while, online personality Alan Krumwiede (Law) spreads profitable fear and misinformation with his bogus conspiracy theories, claiming to have a homeopathic cure made from the flowering forsythia plant. Meanwhile, looting and violence follow widespread terror as the CDC promotes social distancing and state governments shut down borders until they can distribute a vaccine via a lottery system.

Along with the film’s impressive stars, whose roles are more richly developed than one might think possible given their multitude and a runtime of under two hours, are two non-human constants: Cliff Martinez’s electronic score and the disease whose progress Soderbergh charts across the globe. The former is reminiscent of the opening music in George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978), playing like a horror movie designed, with much success, to convey MEV-1’s momentum and leave us with a lasting sense of paranoia. To track the disease’s journey, Soderbergh, also serving as cinematographer under his pseudonym Peter Andrews, shot at locations in Hong Kong, Atlanta, Chicago, Minneapolis, Casablanca, Dublin, London, Geneva, and the San Francisco Bay Area. The real-world locations render a convincing portrait of how a virus would quickly spread in today’s interconnected and overpopulated world, and how people would respond to such a threat. The dialogue is filled with accurate statements about such a disease, such as the R-0 (pronounced “R-naught”), the basic reproductive rate used to determine how quickly an infectious disease will spread through a population. The resulting realism is depicted on an epic scope, unlike anything moviegoers had seen before in a medical thriller. The closest comparison is the decidedly more mainstream effort of Wolfgang Petersen’s Outbreak (1995), with its aggrandized approach to the same basic idea.

What differentiates Contagion from other films about diseases is that Soderbergh and Burns never sensationalize the disease or its outcomes. The screen story’s factual roots and unembellished production design force us to consider the real-life possibilities, unlike the genre-centric narratives of, say, The Andromeda Strain (1971), 28 Days Later (2002) and its 2007 sequel 28 Weeks Later, Cabin Fever (2002), and Carriers (2009). Even though Contagion has shades of a disaster movie, a biological mystery, or even a body horror movie, Soderbergh isn’t interested in sensationalism for commercial marketability. He also resists typical cinematic, gimmicky devices of the pandemic subgenre, such as flashy CGI sequences of the virus moving from one person to the next. One such scene occurs in Outbreak, when, in a movie theater, the camera follows a sneeze that propels invisible droplets of an ebolavirus through the air before they land in a recipient’s mouth. However much I relate to the scene’s frightening possibility after my experience seeing Contagion in the theater, the methods prove Hollywoodized, kitschy even. In other examples, the consequences of a pandemic have monstrous results, turning victims into brain-eating zombies, rage-infected killers, or decaying wads of flesh.

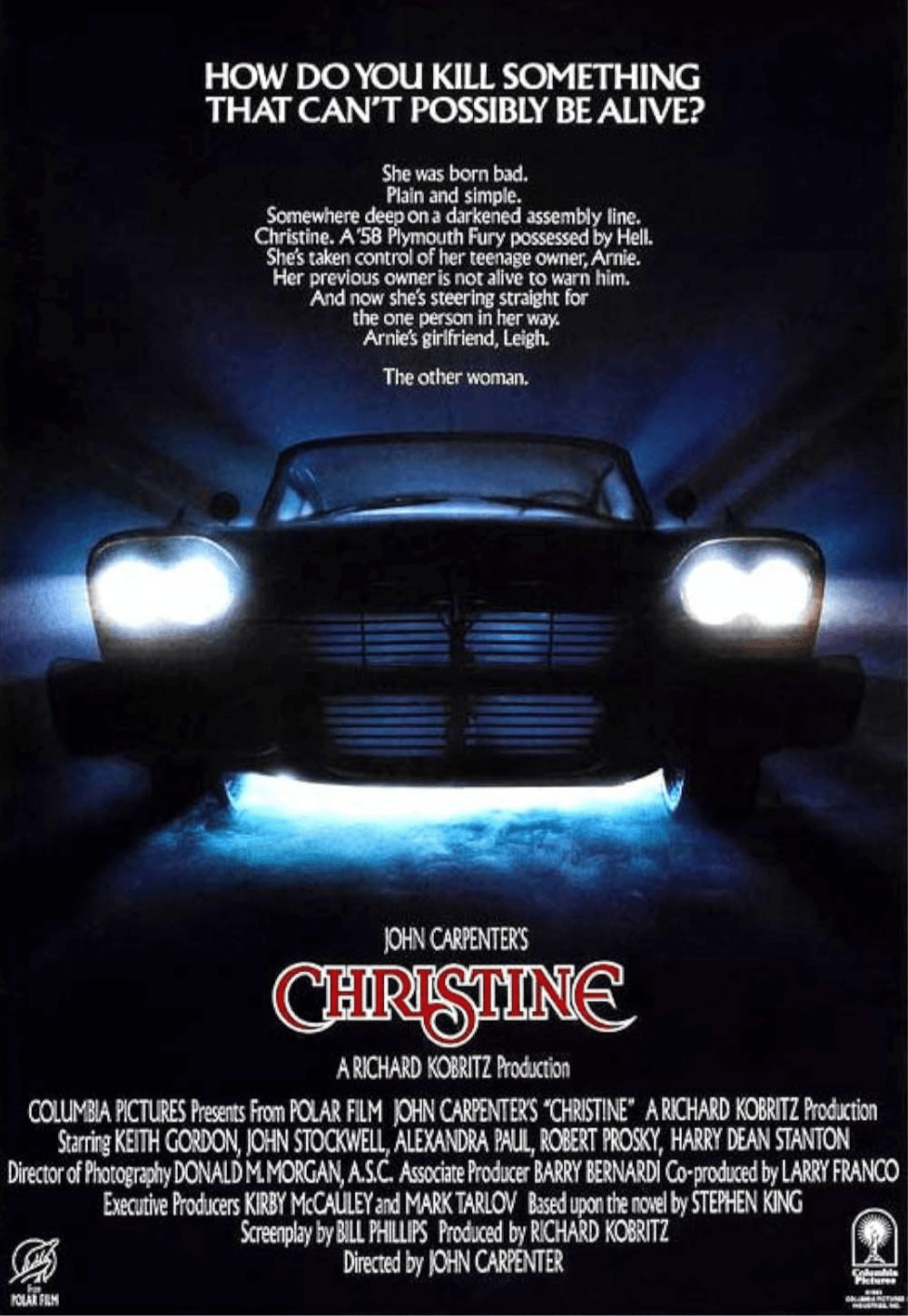

However, the presence of MEV-1 is implied by Soderbergh’s attention to fomites—the sites where the disease is transmitted. Winslet’s Dr. Mears implants our dread early on, explaining that the average person touches their face “three to five times every waking minute. In between, we’re touching doorknobs, water fountains, elevator buttons, and each other. Those things become fomites.” Soderbergh and his frequent editor Stephen Mirrione—who cut together Traffic, The Informant!, and the Ocean’s trilogy—offer moments where the camera lingers on fomites with dread: a community bowl of bar peanuts, a hand railing on a bus, a door at an elementary school. When Gould’s Dr. Sussman sits in a San Francisco bar, he becomes eerily aware of his surroundings. He sees a bartender yawn into his hand and then resume polishing a cup, a woman coughing and then taking a drink, and patrons drinking from contaminated glasses. A moment later, he decides to get out of there. This scene, and several like it in the film, transforms the ordinary into something horrific and potentially deadly. It is the strategy of many a horror writer who turns the ordinary into nightmare fuel (Stephen King alone has imbued so many everyday objects with supernatural qualities that terrify). Soderbergh and Burns suggest that everything you touch may be covered in something that could kill you.

However, the presence of MEV-1 is implied by Soderbergh’s attention to fomites—the sites where the disease is transmitted. Winslet’s Dr. Mears implants our dread early on, explaining that the average person touches their face “three to five times every waking minute. In between, we’re touching doorknobs, water fountains, elevator buttons, and each other. Those things become fomites.” Soderbergh and his frequent editor Stephen Mirrione—who cut together Traffic, The Informant!, and the Ocean’s trilogy—offer moments where the camera lingers on fomites with dread: a community bowl of bar peanuts, a hand railing on a bus, a door at an elementary school. When Gould’s Dr. Sussman sits in a San Francisco bar, he becomes eerily aware of his surroundings. He sees a bartender yawn into his hand and then resume polishing a cup, a woman coughing and then taking a drink, and patrons drinking from contaminated glasses. A moment later, he decides to get out of there. This scene, and several like it in the film, transforms the ordinary into something horrific and potentially deadly. It is the strategy of many a horror writer who turns the ordinary into nightmare fuel (Stephen King alone has imbued so many everyday objects with supernatural qualities that terrify). Soderbergh and Burns suggest that everything you touch may be covered in something that could kill you.

Moreover, Soderbergh does not show the disease onscreen like in Outbreak and other films; instead, he resolves to portray the microscopic disease on diegetic magnified projections or digital models. Nor does he resort to the tactics of Richard Fleischer’s Fantastic Voyage (1966), Joe Dante’s Innerspace (1987), or the animated feature Osmosis Jones (2001), which take the story inside the human body and narrativize its processes. Other films, such as the disease-oriented Canadian auteur David Cronenberg’s Shivers (1975) and Rabid (1977), have shown diseases to operate like parasites that, to some degree, control their hosts, facilitating their spread with an almost conscious motivation. By not showing the disease and portraying humans as the cause of the spread, Contagion makes us acutely aware that the film’s pandemic occurs because of social behavior and economic conditions. The film’s concern is evident from the first frames in black, where the viewer sees nothing but hears a wet cough and thus knows a disease is being spread. The cough belongs to Beth, who sits at a Hong Kong airport bar, looking red-nosed and shiny-skinned, yet she casually eats from the bar’s peanut bowl anyway. Rather than charting the disease in visual terms, Soderbergh charts the spread of the disease through social contact over time with an onscreen title device, which shows how quickly the virus spreads. “Day 2” appears on the screen over Beth before following others: a young man on a Hong Kong ferry, a businessman on a flight to Tokyo, and a Ukrainian model in London. “Day 2” becomes “Day 12” then “Day 131,” and not unlike COVID-19, the disease leaps across continents with disturbing speed.

With a minimalist, almost invisible style, Soderbergh employs a practical outline detailing current procedures to identify, contain, and eliminate a deadly virus. The overarching mission is a race to produce a vaccine and determine patient zero, where the disease jumped from an animal to a human for the first time. Part of Dr. Orantes’ subplot involves using surveillance footage to track the infected people from the Macau casino where they came in contact. Soderbergh’s subtle, straightforward style may raise questions about his directorial signature, with some having called his aesthetic a Hollywood brand of non-style. But these superficial assessments are counteracted by Soderbergh’s clever use of European art cinema techniques and narrative economy that give way to his auteuristic critiques of social and institutional problems—in Contagion’s case, the globalization that facilitated the virus and helped it spread. One immersive sequence tracks Dr. Orantes’ search for the “index case” in a montage with no diegetic audio, just Martinez’s propulsive music. The clarity, brevity, and depth Soderbergh and Burns bring to such passages in Contagion—often through pure visual storytelling—is nothing short of astonishing, balancing the human toll with the efforts of several public health agencies. Soderbergh said he “wanted the style to be really, really simple,” since anything more than a functional aesthetic may have been overshadowing. And while the viewer never feels distracted by Soderbergh’s presence behind the camera, the thematic connections in his work reveal how the director cleverly minimizes the presence of his visual style to underline his themes, characters, and actors’ performances.

Contagion anticipated how some people reacted to COVID-19 in its depiction of empty public spaces, looting, and angry protests, which bring to mind stay-at-home orders, toilet paper shortages, and anti-mask and anti-vaccine dissent in the real world. And Soderbergh’s vast canvas highlights how rampant globalization fuels the spread of MEV-1, turning the narrative into one that impacts all humanity. Despite the film’s planet-wide scope, the director’s approach does not eschew humanity, evidenced in several plotlines, but Damon’s above all. Playing Ben, the immune Minnesotan husband of the disease’s first victim, Damon’s most harrowing moment follows Paltrow’s convincing seizure scene—which doesn’t look like an actor performing a seizure; it seems real—when a doctor tells Ben his wife has died. “Can I go talk to her?” Ben replies, incapable of processing his wife’s passing. Eventually, Ben bursts into a tragic, confused tirade: “What are you talking about?! What happened to her?!” Soon, Ben not only loses his wife but his youngest child, his stepson Clark, leaving him a single father of a teenage girl. Somehow, it gets worse when Dr. Mears interviews Ben about his wife’s whereabouts and inadvertently reveals that Beth may have cheated on him during a layover in Chicago. Unable to bury his deceased loved ones because the mortuary refuses to take infected bodies, Ben attempts to make life tolerable for his quarantined daughter Jory, even arranging a makeshift prom. The plotline predicts the countless stories of parents struggling to maintain their families while living under COVID-19 quarantine protocols, ensuring their children’s safety and finding creative ways to keep them sane.

Contagion anticipated how some people reacted to COVID-19 in its depiction of empty public spaces, looting, and angry protests, which bring to mind stay-at-home orders, toilet paper shortages, and anti-mask and anti-vaccine dissent in the real world. And Soderbergh’s vast canvas highlights how rampant globalization fuels the spread of MEV-1, turning the narrative into one that impacts all humanity. Despite the film’s planet-wide scope, the director’s approach does not eschew humanity, evidenced in several plotlines, but Damon’s above all. Playing Ben, the immune Minnesotan husband of the disease’s first victim, Damon’s most harrowing moment follows Paltrow’s convincing seizure scene—which doesn’t look like an actor performing a seizure; it seems real—when a doctor tells Ben his wife has died. “Can I go talk to her?” Ben replies, incapable of processing his wife’s passing. Eventually, Ben bursts into a tragic, confused tirade: “What are you talking about?! What happened to her?!” Soon, Ben not only loses his wife but his youngest child, his stepson Clark, leaving him a single father of a teenage girl. Somehow, it gets worse when Dr. Mears interviews Ben about his wife’s whereabouts and inadvertently reveals that Beth may have cheated on him during a layover in Chicago. Unable to bury his deceased loved ones because the mortuary refuses to take infected bodies, Ben attempts to make life tolerable for his quarantined daughter Jory, even arranging a makeshift prom. The plotline predicts the countless stories of parents struggling to maintain their families while living under COVID-19 quarantine protocols, ensuring their children’s safety and finding creative ways to keep them sane.

Reflecting on Contagion in a post-pandemic world, the film gets most of its details right, uncannily so. Burns’ script uses buzzwords such as “social distancing,” a term that may have bounced off viewers in 2011 but would become an everyday phrase by 2020. The film’s subplot involving the doctors Hextall and Sussman—who research MEV-1 and, in the former’s case, resorts to extreme measures to test the vaccine’s effectiveness in humans—underscores the heroic role of virologists and other medical professionals. The film’s primary consultant, Dr. Lipkin, called them “the real heroes of this film” for their personal risks to understand the disease and find a vaccine. The medical community also praised the film for the predominance of women scientists depicted. This is rarely the case in Hollywood productions, but Contagion more accurately reflects the gender ratios among medical researchers. More sinister in its accuracy is the subplot involving Krumwiede, who spreads misinformation on a website called Truth Serum Now for profit. Burns has likened Krumwiede’s lies to a disease. Law’s self-serving blogger and conspiracy theorist initially claims the disease is Minamata from mercury in fish. Later, he argues the government intentionally delays production of the vaccine because they hope to profit from pharmaceutical companies. His dangerous, speculative writings ignite suspicion and direct panicky people toward an unverified miracle cure, in which, of course, he has invested. Less a prophet than a profiteer, his brand of fearmongering became popular during COVID-19 and afterward, working its way into politics and the culture war with woefully unqualified sources endorsing false cures (such as chloroquine, ivermectin, and even bleach).

Given these similarities, viewers around the world returned to Contagion to note the film’s eerie prescience both during the COVID-19 pandemic and after. But no matter how many consultants the production had, Contagion could not predict some of the most disturbing and stranger-than-fiction outcomes of COVID-19. Burns admitted that he did not anticipate how the pandemic is experienced by “people who have access to health care versus those who don’t.” Vaccine and testing access, for instance, became a matter of class and privilege during the real-world pandemic. One study in the National Library of Medicine estimated that COVID-19 saw “nearly double the annual mortality,” including “an 11% increase in cases and an 18% increase in hospitalizations” due to lack of health insurance. At the same time, Burns admits that he did not expect how certain people would turn on science out of fear or political motivation. He was surprised to see how “we rely on science in these moments when we don’t understand what’s happening in our world, and then we get very upset and toss science overboard at any given moment in time when it doesn’t have a full understanding because that understanding is evolving.” The pandemic also deepened and radicalized political and social divisions in ways that the filmmakers could not anticipate, which have since persisted, though the worst of COVID-19 remains behind us.

Furthermore, some of what Burns omitted from his script entailed the foreseen xenophobia that often comes with a pandemic, stemming from racial intolerance or politicized prejudice. For instance, during the Black Death in the fourteenth century, thousands of Jews were systematically massacred throughout Europe by Christian communities who accused Jews of tampering with wells and spreading the plague. Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic increased anti-Asian racism and violence propelled by remarks from President Donald Trump, who “legitimatized anti-Asian prejudicial attitudes through political agenda focusing on xenophobia against Asians,” according to one scholarly study. But adequately confronting this topic could have taken an entire film, and reducing it to a mere subplot may not have done it justice. “I didn’t really want to go there,” Burns told journalist Nina Metz. “But clearly there are people in this country who did want to go there and did see a way of using it for political gain.” However, in the subplot involving Dr. Orantes, Burns confronts how prejudice and class prevent some from gaining access to vaccines. Sun Feng believes the small village where he grew up will not receive vaccines with the same speed as privileged Americans, so he arranges for Dr. Orantes to be kidnapped and held to secure vaccines for his people. When WHO complies with the demand, they deliver placebos in exchange for Dr. Orantes’ safety. After she discovers their trick, she promptly returns to the village.

Furthermore, some of what Burns omitted from his script entailed the foreseen xenophobia that often comes with a pandemic, stemming from racial intolerance or politicized prejudice. For instance, during the Black Death in the fourteenth century, thousands of Jews were systematically massacred throughout Europe by Christian communities who accused Jews of tampering with wells and spreading the plague. Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic increased anti-Asian racism and violence propelled by remarks from President Donald Trump, who “legitimatized anti-Asian prejudicial attitudes through political agenda focusing on xenophobia against Asians,” according to one scholarly study. But adequately confronting this topic could have taken an entire film, and reducing it to a mere subplot may not have done it justice. “I didn’t really want to go there,” Burns told journalist Nina Metz. “But clearly there are people in this country who did want to go there and did see a way of using it for political gain.” However, in the subplot involving Dr. Orantes, Burns confronts how prejudice and class prevent some from gaining access to vaccines. Sun Feng believes the small village where he grew up will not receive vaccines with the same speed as privileged Americans, so he arranges for Dr. Orantes to be kidnapped and held to secure vaccines for his people. When WHO complies with the demand, they deliver placebos in exchange for Dr. Orantes’ safety. After she discovers their trick, she promptly returns to the village.

Before the response to MEV-1 could be contrasted with COVID-19, the scenario seemed nightmarish in 2011, and, to a grave extent, it still does. The virus depicted in Contagion is far deadlier than COVID-19. At the time of this writing, WHO associates 6.9 million deaths with COVID-19, whereas the film’s death toll reached over 26 million. Yet, Soderbergh and Burns’ film seems almost hopeful compared to the real-world situation of rampant denial, lack of trust in science, and social consequences. Their assessment of humanity’s response shows isolated scenes of social disorder or exploitation for personal gain, but not to the chilling degree the real world saw misinformation, refusal to accept mask mandates or stay-at-home orders, and anti-vaccine propaganda. However, it accurately shows that a pandemic response is only as good as the weakest link in the plan, and individuals will find countless ways to place others in danger by not adhering to informed scientific or state mandates. Where Soderbergh and Burns’ voices come through in this conversation is their critique of globalization and deforestation when, in the final sequence capped with the title “Day 1,” we see bulldozers toppling the tree that housed a bat, forcing the animal into an area where humans keep livestock. When two animals that might never have met interact because of human influence, a virus is born, and it quickly spreads in the Macau casino. This answer to the film’s mystery, shown only to the viewer in purely visual terms, is tantamount to the camera revealing to the viewer alone that the source of Charles Foster Kane’s last word, “Rosebud,” is his childhood sled.

Surgical in its precision, Soderbergh’s commitment to realism and objectivity supplies Contagion with a warning nearly an entire decade before the arrival of COVID-19, delivered with a restrained style and terrific cast. Today, Burns’ well-researched science and plausible scenario amount to a frightening reflection of our world during the real-life pandemic, along with an informed thesis on why globalization will continue to birth viruses of this kind. Even knowing what we do now because we survived, it’s disturbing to go back to a world with people who still shake hands and cough into their fists instead of their arms. Beyond its foresight, the film provides a stirring example of how Soderbergh’s pictures often have an independent production’s aesthetic and social concerns, and general audiences might not see them except that he exploits his A-list ensemble to ensure their commercial viability in Hollywood. But take away the extratextual factors from Contagion, and it’s an unsettling and hypnotically watchable deconstruction of a biological disaster that, even after living through a scenario that seemed impossible in 2011, is capable of leaving viewers with an unshakable sense that another pandemic might not be far off. In a career of films that regularly question established systems, Contagion remains Soderbergh’s most impactful cautionary tale for the human species and perhaps his most relevant yet engrossing picture to date.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on September 20, 2023. Many thanks for your continued patronage and support, Lyra!)

Bibliography:

Baker, Aaron. Steven Soderbergh. Contemporary Film Directors. University of Illinois Press, 2011.

—. “Global Cinema and Contagion.” Film Quarterly, vol. 66, no. 3, 2013, pp. 5–14. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2013.66.3.5. Accessed 6 September 2023.

Benson-Allott, Caetlin. “Out of Sight.” Film Quarterly, vol. 65, no. 2, 2011, pp. 14–15. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2011.65.2.14. Accessed 6 September 2023.

Campbell, Travis, et al. “Exacerbation of COVID-19 mortality by the fragmented United States healthcare system: A retrospective observational study.” The Lancet Regional Health–Americas, vol. 12 (2022): 100264. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2022.100264. Accessed 8 September 2023.

“Contagion.” Charlie Rose. 14 September 2011. https://charlierose.com/videos/15877. Accessed 6 September 2023.

“Contagion Consultants Talk About the Movie’s Scientific Accuracy.” The Washington Post. 12 September 2011. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/contagion-consultants-talk-about-the-movies-scientific-accuracy/2011/09/08/gIQAVOkUNK_story.html. Accessed 6 September 2023.

DeWaard, Andrew and R. Colin Tait. The Cinema of Steven Soderbergh: Indie Sex, Corporate Lies, and Digital Videotape. Wallflower Press, 2013.

Dixon, Deborah P., and John Paul Jones. “The Tactile Topologies of ‘Contagion.’” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 40, no. 2, 2015, pp. 223–34. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24583381. Accessed 3 September 2023.

Everett, Wendy. “Fractal Films and the Architecture of Complexity.” Studies in European Cinema. 2,3: 160, 2005.

Gallager, Mark. Another Steven Soderbergh Experience: Authorship and Contemporary Hollywood. University of Texas Press, 2013.

Kaufman, Anthony. Steven Soderbergh Interviews. Jackson University Press, 2002.

Lantz, Brendan, et al. “Fear, political legitimization, and racism: Examining anti-Asian xenophobia during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Race and Justice: An International Journal, 13(1), pp. 80–104, 2023. doi:10.1177/21533687221125817. Accessed 5 September 2023.

Metz, Nina. “I couldn’t bear to watch ‘Contagion’ last year, but I rewatched it recently and asked the screenwriter what he would change.” Chicago Tribune, 6 May 2021. https://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/what-to-watch/ct-mov-revisiting-movie-contagion-a-year-into-the-pandemic-20210506-rjsgxcmerfachnfqfsgqm6fbya-story.html. Accessed 1 September 2023.

Morris, Wesley. “For Me, Rewatching ‘Contagion’ Was Fun, Until It Wasn’t.” The New York Times, 10 March 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/10/movies/contagion-movie-coronavirus.html. Accessed 3 September 2023.

Palmer, R. Barton and Steven M. Sanders. The Philosophy of Steven Soderbergh. The University Press of Kentucky, 2011.

Santhakumar, Arthy. “FILM: ‘Contagion.’” The World Today, vol. 67, no. 11, 2011, pp. 15–16. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41962595. Accessed 9 September 2023.

“Steven Soderbergh Talks Contagion.” Ain’t It Cool News. September 8, 2011. http://legacy.aintitcool.com/node/51119. Accessed 6 September 2023.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review