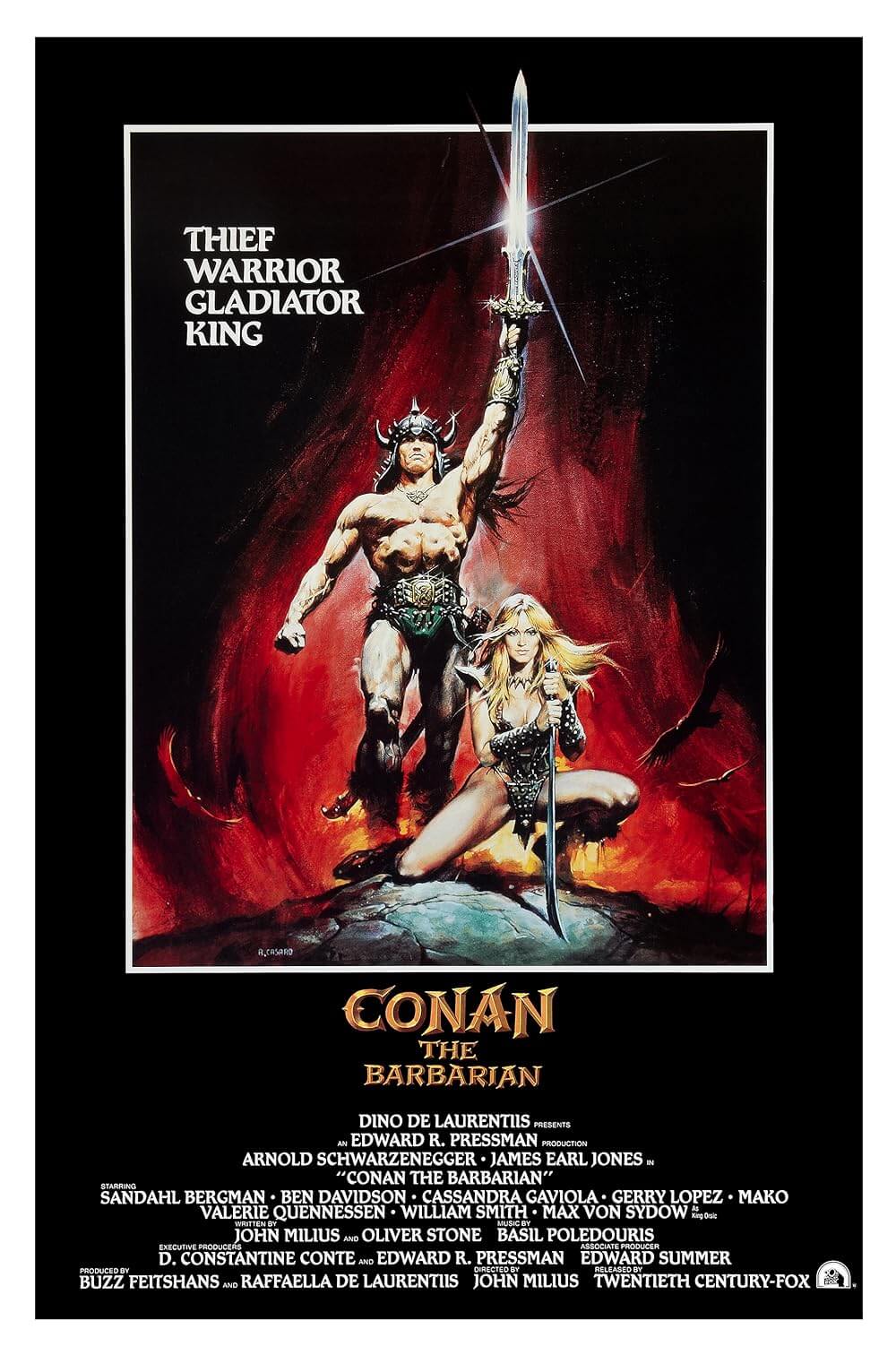

Conan the Barbarian

By Brian Eggert |

No other evocation of the “Sword and Sorcery” genre is as pure and unadulterated as Conan the Barbarian, the 1982 film which embodies the narrative economy of Robert E. Howard, who created the character in the 1930s, and the visual iconography of Frank Frazetta, the artist whose paintings adorned the resurgence of Howard’s books in the 1960s and beyond. Epic storytelling comes by way of bloody swordfights, brawny heroes, evil wizards, hideous serpents, and scantily clad women. And yet, instead of playing on the character’s sometimes comic book mentality (as its sequel Conan the Destroyer does), director John Milius maintains the picture’s dignity by avoiding campy humor and embracing a serious myth-making tone—he avoids swashbuckling antics and allows the film to unfold like an ambitious pulp novel rather than a mindless adventure.

In the late 1970s, producer Dino De Laurentiis saw potential in the mainstream popularity of the relatively new “Dungeons & Dragons” game and hired screenwriter Oliver Stone to adapt similar Conan stories for film. Howard’s Conan made his debut in 1932 in the pages of Weird Tales and continued in 18 published novels (and several other unpublished texts) before his suicide in 1936. Not until the 1960s did Conan resurface when scribes Lin Carter and L. Sprague De Camp sought to revitalize Howard’s original stories, as well as author new tales of their own. Here is where Frazetta’s artwork, assuming the covers of Howard’s rereleased books, became forever associated with the Conan legend. Later, in the 1970s, Marvel Comics launched a Conan the Barbarian comic, which ran until 1993. Working from these sources at the time, Stone and co-writer Milius streamlined the character, transforming him into an austere creature of silent, primal motivations against which many Howard purists rebuff. Howard’s sometimes well-spoken character becomes a personification of untreated masculinity, a one-note animal of mythic origins reflected in Milius’ stark pitch.

Prefaced by Friedrich Nietzsche’s maxim “That which does not kill you makes you stronger,” the film opens sometime around 12,000 B.C. with the young Conan (Jorge Sanz) learning about his Cimmerian god Crom and “The Riddle of Steel” from his father. Moments later, Conan’s family has been slaughtered by the despotic wizard Thulsa Doom (James Earl Jones). The boy becomes a slave, forced to push a grain combine called “The Wheel of Pain” around in circles each day until adulthood, by which time Conan’s daily toils have brought about the musculature of a bodybuilder. He is now played by Arnold Schwarzenegger, in the role that made him a star. Conan’s masters force him into gladiatorial bouts, where the massive barbarian learns the glory of triumph. After countless victories, his masters take him to the Far East to teach him the ways of battle and war, and soon they let him go free, the animal too large and too smart to be held captive. On his own, he makes a name for himself as a thief with his bandit-lover Valeria (Sandahl Bergman) and archer-sidekick Subotai (Gerry Lopez). Eventually, they confront Thulsa Doom, and Conan earns glory in his long-awaited vengeance.

In many ways, the audience for this film is limited to those familiar with Howard’s books, as the majority of viewers could easily, and understandably, misinterpret the film as base masculine exploitation. Here’s a film that may be contemptible without its Nietzschean philosophy foreword informing every moment of its raw form. Howard, and therefore Milius, present an alternate ancient history and embrace it fully, complete with questionable illustrations of the sexes. Aside from Valeria, women play subordinate roles; when they’re not robed for prayer, they’re often topless or chained to a pillar, in need of rescue. But it is key to remember that this is Howard’s fictionalized prehistory, which imagines a time after dinosaurs but before recorded history, where civilization had barely emerged from its cradle. Therefore, the sexes are reduced to their most basic pre-civilized historical assignments; men are brutish killers, and women are objects, all to represent a stripped-down version of the human will to survive. And with the exception of Valeria, whose depiction still deems her a “sexy warrior,” such broad portrayals would be contemptible out of their archaic pseudo-historical context.

Likewise, it would be all too easy to dismiss Milius’ film as a product of Schwarzenegger-brand cheese, as critics have sometimes done. Indeed, most admirers view the film as a guilty pleasure enjoyed for its perceived campy qualities so often associated with the genre. Its detailed production values designed by Ron Cobb (Alien and Aliens), simple and believable, and attractive on-set open-air shooting are overlooked due to unfair prejudice against the subject matter. The same can be said for Basil Poledouris’ rousing score, a booming, grandiose piece of music among the best and most memorable scores of the 1980s. Granted, seen through the eyes of moviegoers uninterested or unfamiliar with Conan or the fantasy adventure genre, moments from the film would seem unintentionally funny, filled with 1980s production values comparable to jokey subsequent efforts like The Beastmaster (which opened two months after Conan the Barbarian), Conan the Destroyer (1984), and Red Sonja (1985). But, much in the way that Hayao Miyazaki elevates animation or Christopher Nolan brought class to superheroes, Milius has loftier goals, and Nietzschean values ingrained into its violence and sexuality.

Milius’ treatment lends a history-in-the-making feel to every scene, and the screenplay embraces its philosophy so fully that one cannot help but feel Thulsa Doom represents religious power, namely some warped prevision of Christianity equally reliant on iconography (his symbol is a two-headed snake), usurped by the rawness of man. Conan learns early on there’s little use in praying to Crom—the greatest power on Earth is the human will. This point is brought to a head (pun intended) when Conan rises to the top of Thulsa Doom’s Mountain of Power and decapitates him before his assembly of followers, and then drops his head to roll down a long series of steps. Here, in full Nietzschean grandeur, man kills god. Milius’ purity of storytelling does not pull punches for the sake of the audience’s sympathy for the hero, either. For instance, Conan’s selfish desires as a thief, his self-satisfied gluttonous celebration, and his complicity in animal-like breeding by his masters suggest an amorality to his characterization. After all, the film is called Conan the Barbarian, and not Conan the Humanitarian.

As a result, Schwarzenegger is perfectly cast, his character requiring little by way of emotional range and motivation beyond flexing his muscles or bellowing a battle cry. He must simply occupy the corporeal form with which Conan has been associated. And, thanks to the Franzetta-inspired poster illustrated by Renato Casaro, Conan becomes a living incarnation of Howard and Franzetta’s design. To be sure, refined acting is not one of the film’s strongest suits. The immediate supporting cast, namely Bergman and Lopez, give wooden performances, whereas Milius tasks Jones with underplaying his villain’s evil. Rather than forcing his character to perform demonic acts to demonstrate his malevolence through cartoonish broad strokes, he trusts Jones to communicate his character’s sedition slyly, through his eyes. Long, ponderous shots stare into the actor’s intense eyes until, suddenly, Milius transforms Thulsa Doom into a snake using effective-if-modest makeup designs. Max von Sydow (The Seventh Seal) also appears in a cameo as the melancholic King Osric, by far the best acting offered in the film.

Obviously, not everyone will appreciate an epic tale of masculine prowess and religious indictment starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, who’s splashed with blood and ornamented by thirty-year-old special effects. But with Conan the Barbarian, Milius achieved something unique among such genre adaptations in the 1980s. Instead of placating his audience with a safe, PG-rated adventure, Milius does the opposite and narrows his viewership with an R-rated epic driven by some heady ideas and a concentration on narrative over adventurous derring-do. From a commercial standpoint, Milius employed near-suicidal artistic integrity, a decision evident in the underwhelming (yet profitable nonetheless) box-office returns, and one which De Laurentiis would correct with the family-friendly sequel. Conan fans know there’s nothing family-friendly about his legend, and while Milius tampers with the cannon with his adaptation, in spirit, he captures Howard’s stories like no other subsequent film has.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review