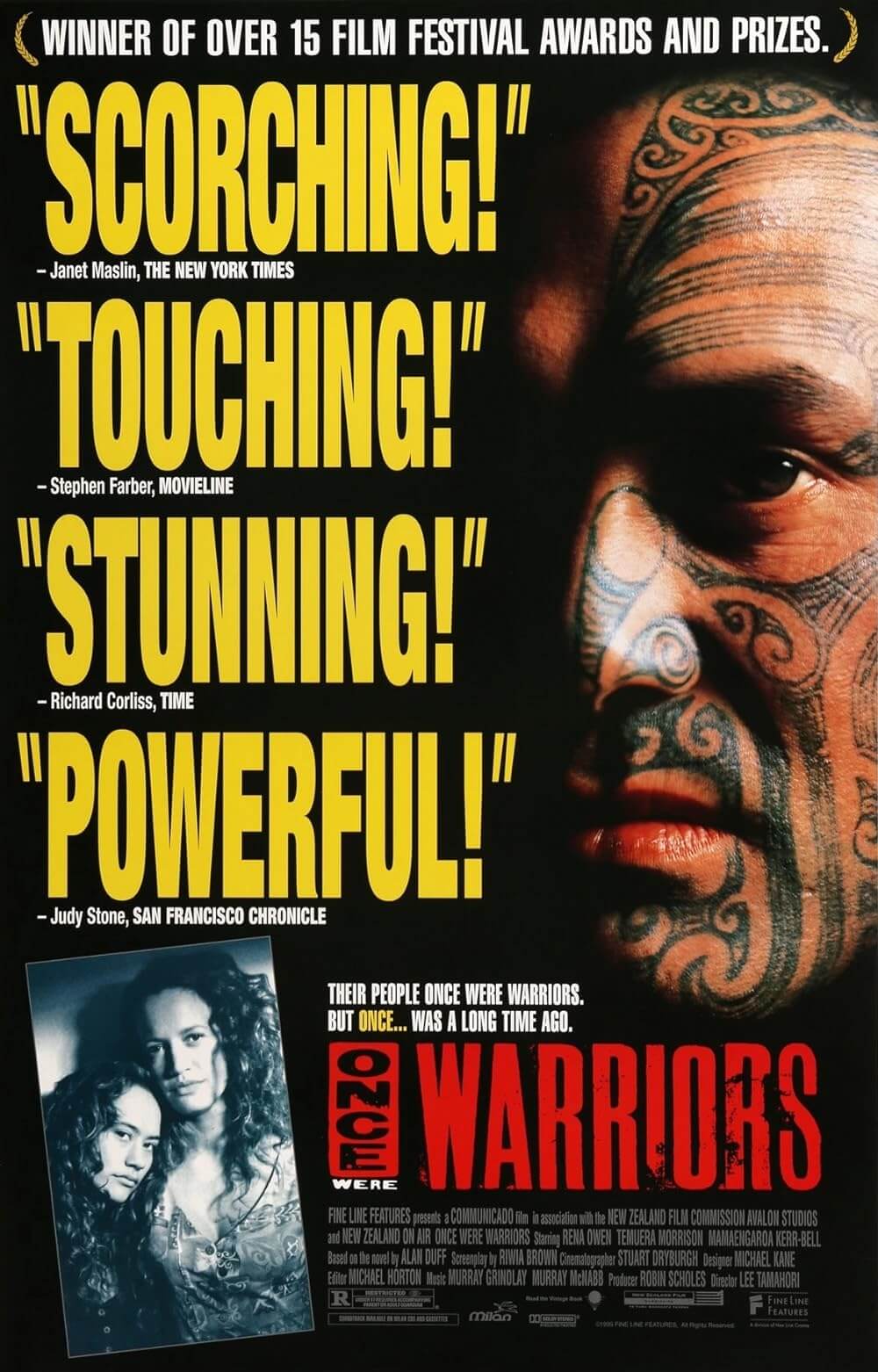

Collateral Beauty

By Brian Eggert |

Collateral Beauty means well by attempting to look into the abyss of parental grief over a lost child, but its cloying premise trivializes its subject matter with whimsical plot twists and forced schmaltziness. A superficial attempt to pluck our heartstrings, the movie operates in barefaced conceits, unashamed about its worthiness of the Hallmark Channel. Its attempts at true sentiment serve up a series of empty platitudes, grandiose speeches, and a silly domino metaphor—all with hopes of being deeply moving; instead, it’s a transparent effort to manipulate its viewers. Every so often a movie like this comes along, and I feel an urgent duty to present a review that is also a warning. Collateral Beauty should be seen by no one, not even ironically, as its device-laden attempt to draw out tears remains calculating, absurdly structured, and borderline offensive in a made-for-TV sort of way.

Directed by David Frankel from a screenplay by Allan Loeb, Collateral Beauty may go down in history as one of the worst uses of one of the very best ensembles ever. Will Smith leads the roster of Edward Norton, Kate Winslet, Michael Peña, Naomie Harris, Keira Knightley, Helen Mirren, and Jacob Latimore. They’re all living in New York City around the holidays, so twinkling lights and snowfall add the necessary ingredients for a standard Hollywood feel-good sauce. The story follows Howard (Smith), a former advertising entrepreneur who, after losing his six-year-old daughter to a rare form of cancer, has been virtually catatonic for years. When Howard’s inaction threatens to sour his company, three of his friends/coworkers concoct an elaborate scheme that will either break him out of his sorrow, or it will demonstrate to the company’s board that he’s unfit to lead.

Rather than, say, force Howard into counseling or corner him in an intervention, Whit (Norton) resolves to hire a private investigator (Ann Dowd). The P.I. reports back that Howard has written and mailed therapeutic letters to Death, Time, and Love, three concepts that factored heavily into his own personal philosophy of advertising—an abridged version of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Whit convinces Howard’s other two friends, Claire (Winslet) and Simon (Peña), to hire three actors to portray personifications of Death, Love, and Time. Fortunately, Whit just-so-happens to locate a trio of off-Broadway performers (Mirren, Knightley, and Latimore) willing play these roles, albeit for a price. Even though the job consists of about a day’s work, the actors demand $20,000 each. Fortunately, everyone in Collateral Beauty is impossibly well-to-do and can deliver the requested payment in cash without much fuss.

The Master Plan requires the actors to play Death, Time, and Love, and then confront Howard in public to force a conversation, the result of which will be recorded. Later, Whit plans to digitally remove the actors, so it appears as though Howard is talking to himself, which in turn will demonstrate to the board that Howard is not mentally sound. This insanely elaborate and cruel prank on a heartbroken man hardly seems like the work of a friend—and the fact that Howard’s friends all agreed to such an absurd scheme is a testimony to their awfulness. Meanwhile, as Howard goes somewhat mad after being confronted by nonexistent spirits, his friends realize they have their own issues with Death, Time, and Love: Simon faces a cancer prognosis; Claire wonders if she’s too old to have a child; Whit tries to reconnect with his estranged daughter, who refuses to speak to her philandering father.

Loeb juggles several story contrivances at the same time, each more convenient than the last. Consider how Howard lingers outside the window of a grief counseling group run by Madeline (Harris). She lost a child, too, and she seems interested in Howard, presenting a probable romance and hopeful future between the two by the finale. Not only does the romance blossom, but it turns out Howard and Madeline were actually married previously; they both suffered the same loss of their child. Even more convenient, after resolving the personal issues of Whit, Claire, and Simon, the actors reveal themselves to be the actual personifications of Death, Time, and Love. Or maybe they’re spirits, or angels, or something else. Who knows. Whatever they are, by the time they magically disappear in the final scene, the audience has had enough and feels like giving the movie the middle finger.

Collateral Beauty insults with the fantastical way everything works out, especially in the face of such aching tragedy. For a moment there, the movie almost seemed like it would address some hard truths about unrelenting loss. However, all of Howard’s pain disappears when his own trifecta of human needs just-so-happens to actually have mystical substance and—POOF!—all is resolved. Of course, it should come as no surprise that Frankel also directed Marley & Me, another ridiculously manipulative movie. Collateral Beauty is the kind of feature where the viewer gets a full view of the chef as he bakes us a pie with excrement filling. He takes the pie out of the over and presents it to us, to which we must respond, “No, thank you. Keep your shit pie.”

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review