Coco

By Brian Eggert |

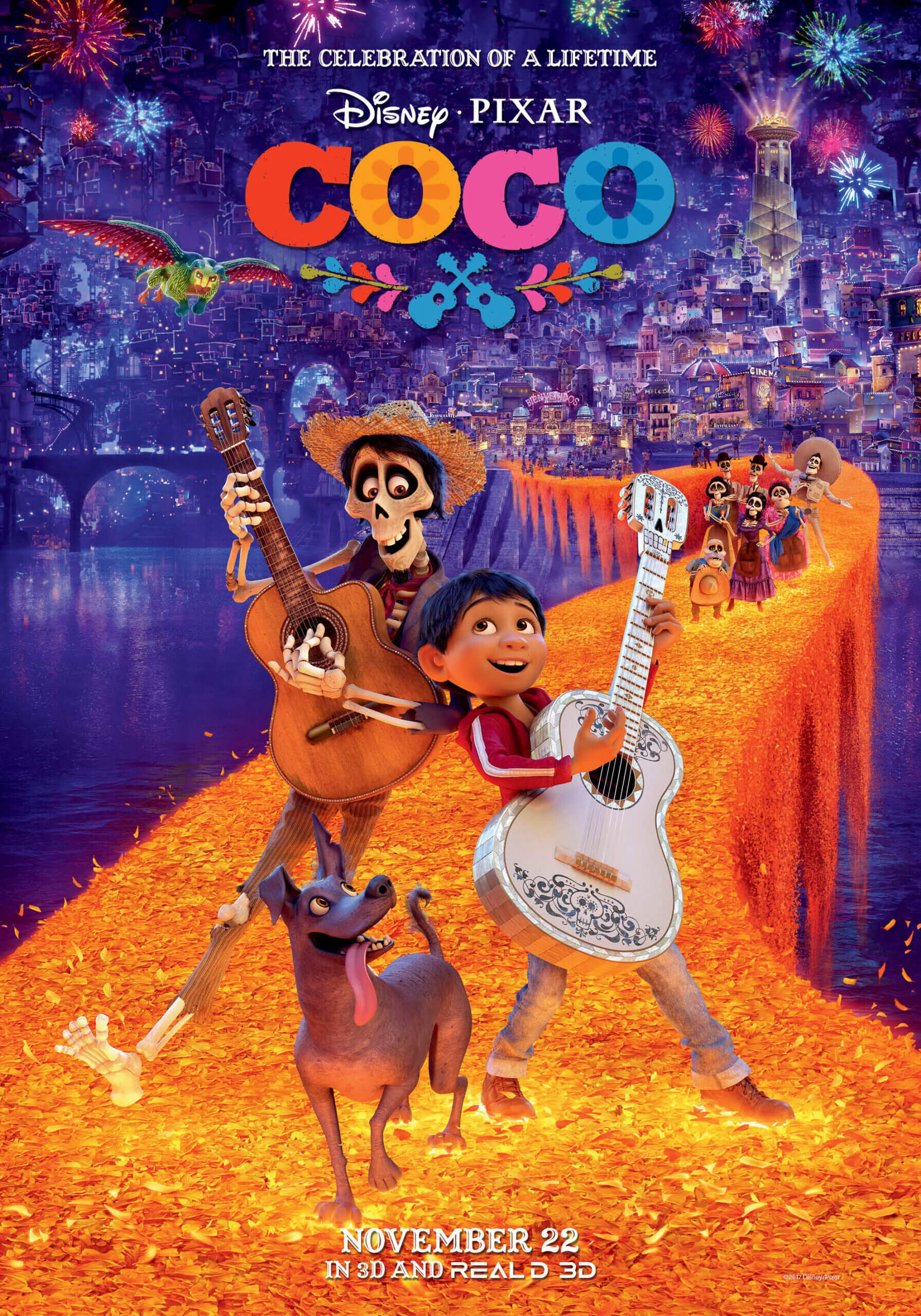

Every so often, but not often enough, a film comes along with such stirring visuals that tears begin to well up, and the viewer feels overcome by the transcendent beauty onscreen. There are several moments with this effect in Pixar’s Coco, the premier animation studio’s 19th feature and one of their finest in the last decade. When its young hero, the twelve-year-old Miguel Riviera (voiced by Anthony Gonzalez), crosses a bridge of bright orange Aztec marigolds and looks at the bustling afterlife metropolis populated by millions of the skeletal deceased, he freezes in wonder. The viewer might not even notice that director Lee Unkrich (Toy Story 3) and his co-director Adrian Molina—both longtime Pixar writers, animators, and artists—hold the shot as long as they do. In that instant, our eyes and emotions have been fully engaged, as have Miguel’s, and the shot gives us more than our brains can process in the time allotted, maintaining a profound sense of wonder and curiosity. Coco is a film that reminds us of the effect and importance of mise-en-scène, even when it has been assembled by animators and computers.

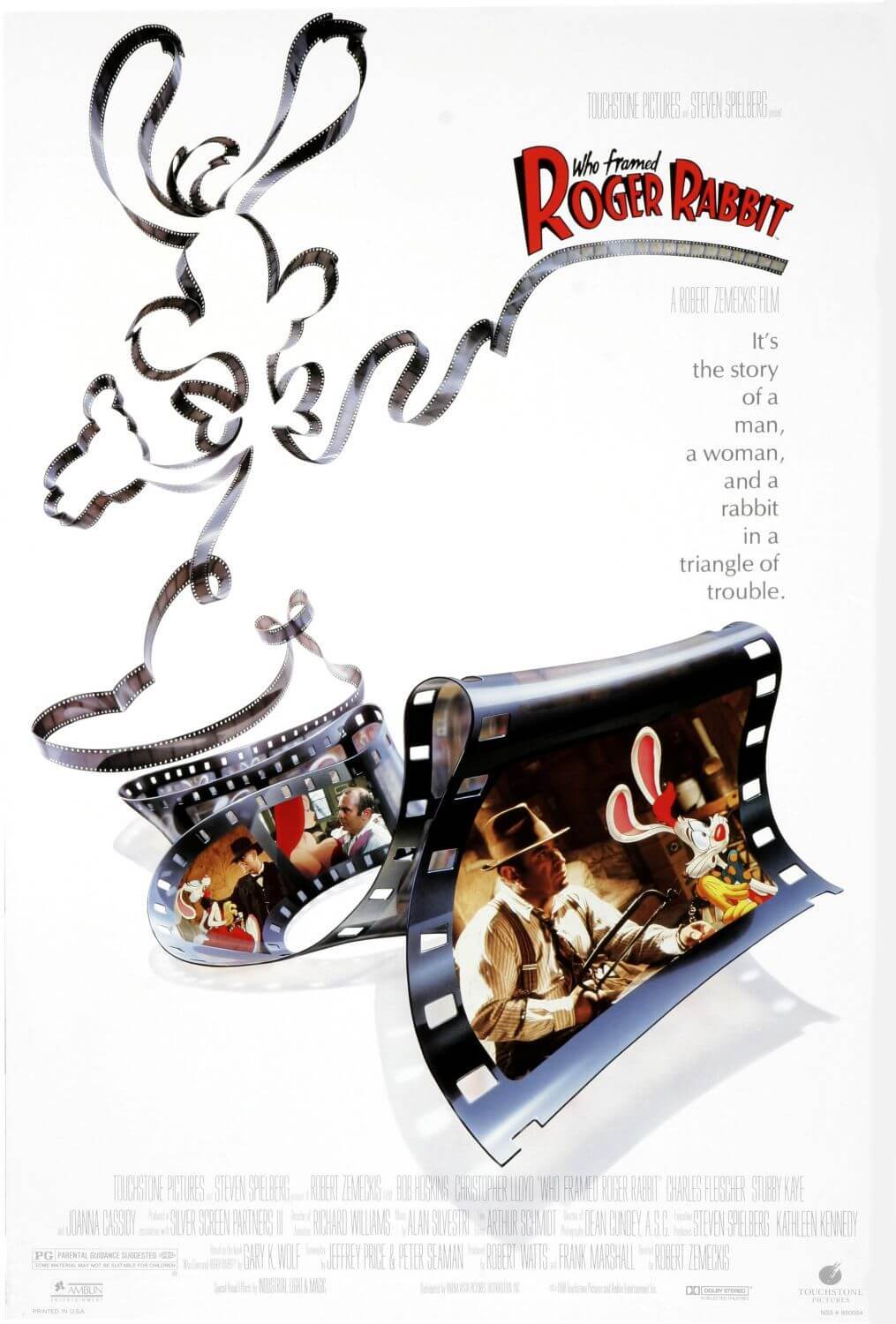

Adopting rich cultural iconography, Pixar explores material already tapped by Fox in 2014’s The Book of Life. Both films involve the Mexican holiday Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead), a guitar-playing hero entering the underworld laden with fluorescent colors, and skeletal characters for a mix of morbid family humor and adventure. But weighing the two is like drawing a comparison between Roger Corman’s Carnosaur and Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park; they both opened in 1993 and feature escaped dinosaurs, though the result is acutely different. Coco also happens to be the first entirely non-white Pixar film, offering a degree of cultural diversity that goes beyond Samuel L. Jackson’s black Frozone in The Incredibles (2004) or the Asian American scout Russell in Up (2009). The film also strays from the jealously U.S.-based perspective of most animated features, steeping the viewer in a Latin-American cultural identity—complete with alternative representations of spirituality, religion, and family values.

Set in the small town of Santa Cecilia, Coco follows Miguel’s unlikely passion to play the guitar, which—not unlike the Parisian rodent Remy from Pixar’s Ratatouille (2007) or the isolated robot in WALL·E (2008) who yearns for companionship—remains a distant dream given the limitations set upon him. Miguel idolizes the great Mexican film star Ernesto de la Cruz (Benjamin Bratt), a singer-songwriter of early cinema who has long since died, and dreams of performing like de la Cruz someday. He watches the star’s old movies, where he’s learned to sing and play guitar, but he must keep his passion for music a secret. The elaborate, but surprisingly uncomplicated Riviera family history tells of Miguel’s mysterious great-great grandfather, a famous musician, who abandoned his family to play music. Ever since, the Rivieras have been shoemakers and forbid any performance of music in their home, sometimes harshly enforced by his grandmother, Abuelita (Renée Victor). Miguel’s oldest living relative, his great-grandmother Mamá Coco (Ana Ofelia Murguía), a melancholy and wrinkled shell, remains hunched in her chair, with fading memories of the family’s history. The photos of Miguel’s departed ancestors have been staged on the family’s ofrenda, a table of offerings meant to invite remembered family spirits home on the annual Día de los Muertos celebration.

Despite being barred from playing music, Miguel resolves to steal the guitar in de la Cruz’s local mausoleum, but stealing from the dead on the Día de los Muertos means Miguel has been cursed—subject to a katabasis, the Greek term for a classical adventure into the underworld. Miguel begins his descent alongside his unofficial companion, the stray Xolo (a breed of Mexican hairless canine) named Dante, a sort of goofy and clumsy, but not altogether useless, animal sidekick. Together, they search the underworld to secure a blessing from Miguel’s ousted ancestor, none other than de la Cruz himself, which will allow the boy to return to the land of the living, but also give him the familial right to play the guitar. Meanwhile, as one might expect, the dead aren’t accustomed to having a member of the living in their city. With the help of a tragic loner, Hector (Gael Garcia Bernal), Miguel hides behind skeleton facepaint and searches for his family origins.

Many of the rules established for the land of the dead seem complicated and intricate, but Pixar has a habit of storytelling so efficient that such detailed world-building seems almost oversimplified. For instance, Miguel cannot remain in the afterlife forever; he has only until morning, and over the course of his odyssey, he gradually fades into a skeleton. Similarly, Hector has begun to fade. The dead remain in the underworld city only so long as their living family remembers them. Hector has no family to place his photo on their ofrenda, and so he helps Miguel in exchange for displaying his photo to ensure he is not forgotten. Miguel’s skeletal ancestors, led by his great-great grandmother Mamá Imelda (Alanna Ubach) who first started the family’s ban on music, try to recover him from Hector, helped along by vivid, glowing spirit animals called alebrije. Some of the plot machinations may seem obvious, including a twist that comes as no surprise at all. But the emotional weight of the narrative lends substance to Miguel, making every step in his journey a significant one.

Pixar deserves recognition for the respectful and impassioned portrayal of cultural specificity and detail in Coco, achieved as Unkrich and Molina invited their crew on several trips to Mexican cities for research—visiting churches, cemeteries, markets, and family homes to ensure the film contained an accurate representation of Mexican traditions and Día de los Muertos festivities. Although Unkrich originally conceived the story, Molina and Matthew Aldrich incorporate the kind of personal details that remain unique to a multi-generational Mexican household. The film’s music also bears a distinct cultural signature. Michael Giacchino composed the score, using an orchestra comprised of many Latin American musicians who used instruments (like bamboo flutes and Aztec percussives like drums, rasps, rattles, and shakers) outside of the usual orchestra norm. The many songs in the film (“Remember Me” is an instant classic) prove memorable and astoundingly performed, especially those by the 12-year-old Gonzalez, whose love for Mariachi is evident.

But the lovely aesthetics and heart of the narrative occupy the center stage. When so many films contain unmemorable visuals, the mise-en-scène in Coco has been labored over by hundreds of animators to create something uncommonly beautiful. There are moments when the eyes wander about the screen, lost in fascinating details. In one sequence, Miguel and Hector have been dropped into a sinkhole with groundwater at the bottom, and the animated water appears photoreal. And while the skeleton characters take cartoony shapes and have expressive movements, the up-close grooves in their bones looks meticulously drawn. Elsewhere, Coco features several references to Frida Khalo, including an appearance by the iconic Mexican artist in all of her self-obsessed, uni-browed, and fiery glory. Somehow Pixar has rendered what the surrealist female painter might have been working on had she assembled a stage performance combining video, dancers, and conceptual metaphors—achieving one of the film’s biggest laughs.

Enchanting and heartwarming, Coco is an unabashed love letter to Mexican culture and folklore, realized through some of Pixar’s best and more expansive animation yet. Although some of the story beats may seem predictable, as suggested above, those few moments are completely eclipsed by the film’s visual spectacle and engaging emotional pull. Miguel’s eventual performances and the family dynamics of the Riviera clan have impressive, but never oppressive, dramatic heft. With an appreciation for fine art, classic cinema, and nods to countless sources of Mexican culture, Coco also offers a few timely, perhaps unintentional subtexts that celebrate a marginalized (and downright oppressed) people and also warn against celebrity worship over familial bonds. It’s all balanced and made remarkable by Pixar’s well-polished, unchallenged mastery of modern animation. Suffice it to say, I loved Coco, what it showed me, how it made me feel, and what it represents.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review