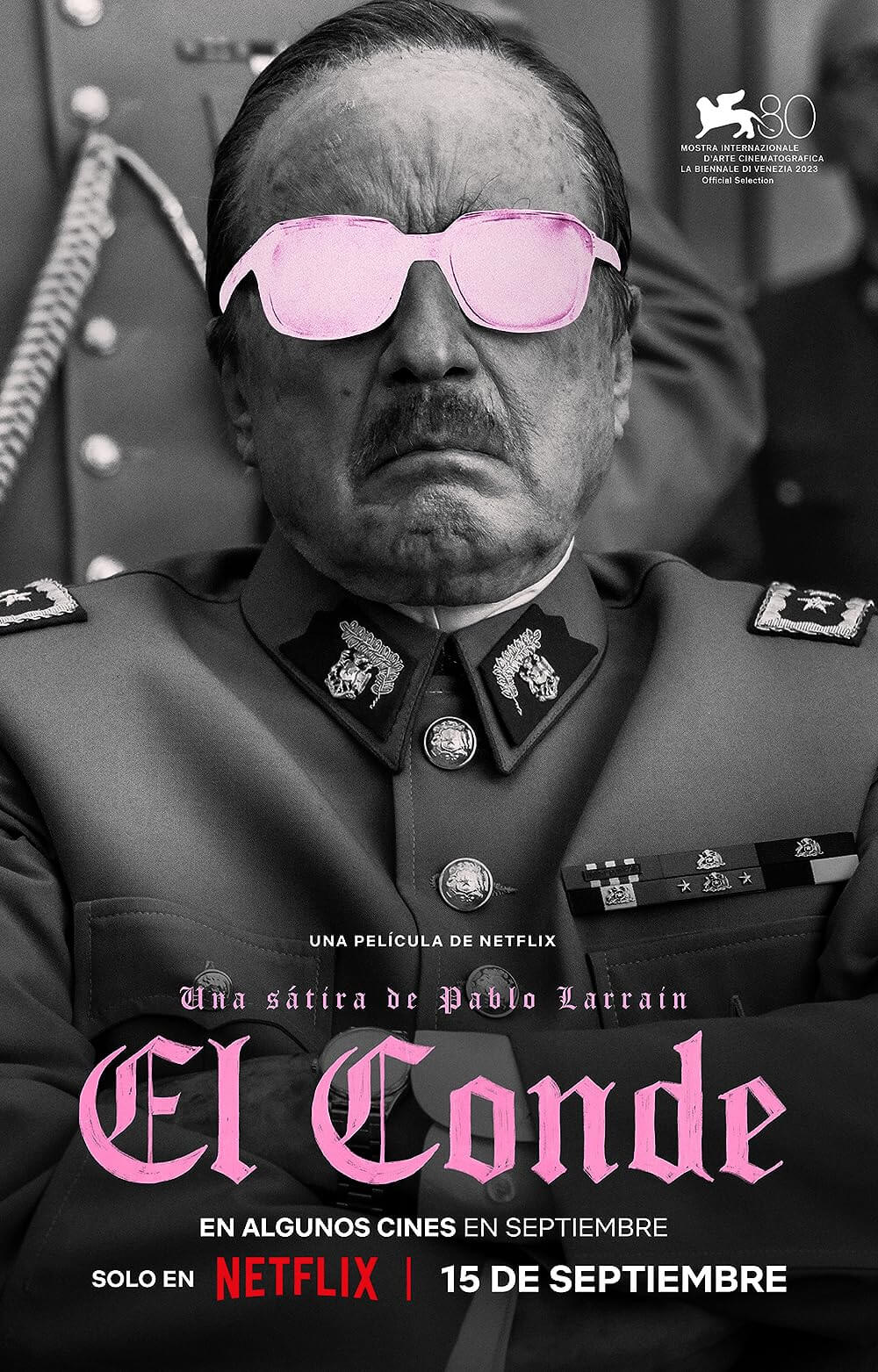

Club Zero

By Brian Eggert |

Club Zero opens with a trigger warning about “behavior control and related eating disorders,” which does the ensuing film a disservice by preparing viewers for its portrayal of brainwashing. With that preface, viewers will actively look for the signs of manipulative behavior instead of gradually realizing for themselves how a warped nutritional instructor indoctrinates her pupils, ultimately convincing them that eating isn’t necessary. But we live in a world of viewers incapable of looking beyond surfaces and reading a film, hence the backlash against Club Zero after its premiere at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, where some accused the story of glorifying eating disorders. This is such a woefully thoughtless take that, in recent comparisons, it is only outdone by those who see Poor Things as somehow endorsing pedophilia, suggesting that perhaps every new release must be accompanied by a written mission statement from the filmmakers to the audience, outlining the intended themes and lessons within the picture. While one of the great things about art is that everyone can form a unique interpretation, sometimes an audience fails to live up to art’s potential.

Setting aside the phenomenon of viewers interpreting the opposite of an artwork’s intended message, Club Zero comes from Austrian director Jessica Hausner, who co-wrote the screenplay with Géraldine Bajard. In the press notes, Hausner describes her film as a critique of parents who don’t make enough time for their children; a portrait of belief systems that reward fasting as a method of self-control and sacrifice; a fairy tale in the vein of The Pied Piper, where “exaggeration to the extent of absurdity” conveys a lesson but also makes the lesson more palatable. With its various targets and themes, the story is not a literal one; it’s designed to prompt discussion about the dynamics between parents, children, and teachers, and how quickly ideology can be changed. Children, especially teens, latch on to political ideas and fight for change, yet their desire to make an impact can be preyed upon and almost weaponized into a form of manipulation.

If that all sounds quite heavy, it is. Yet, Club Zero has the quality of a deadpan joke delivered by a meticulous, acerbic comic. Think Anthony Jeselnik in cinematic form. Set at a boarding school called The Talent Campus, the story follows the hiring of a new teacher, Miss Novak (Mia Wasikowska), who has developed a personal brand related to self-control, using her method of “conscious eating.” When she first meets with her students, she asks them what they desire for their future, and they share their many aspirations, including a healthier lifestyle, ecological sustainability, closing the economic divide, better grades, and jumping higher on the trampoline. In turn, she promises that eating less (for instance, a single potato wedge for lunch) and being more mindful about dietary choices (slower eating, smaller bites) will give the students what they want. But only if they conform to her radical mode of nonconformity, which, being teens, sounds appealing because, as one student put it, “It’s healthy, strengthens my willpower, and improves the environment.”

Once her students are hooked, Miss Novak heightens her lessons. By not eating, she argues, they can prompt autophagy, otherwise known as the cellular recycling process. Most people are “convinced they need to eat in order to live,” Miss Novak says, but this is wrong. She explains that not eating anything, ever, means her students will be part of an exclusive, underground club—hence the title—of people who have taken a stand against Big Food, who are members of a “worldwide association of people who don’t eat.” While at first some of the parents sound open to, if somewhat skeptical of, conscious eating, no food whatsoever raises an alarm. Take Elsa (Ksenia Devriendt), a student who already has bulimia, a condition her mother (Elsa Zylberstein) pretends she doesn’t notice. When Elsa switches to Miss Novak’s extreme form of anorexia, her father (Mathieu Demy) attempts to force her to eat. But Elsa’s rebellion against her parents is a gag-inducing display of eating her own vomit. Each of the students take their commitment to Miss Novak to disturbing levels, from one student forgoing his insulin shots to the finale—an ambiguous image that invites speculation.

Once her students are hooked, Miss Novak heightens her lessons. By not eating, she argues, they can prompt autophagy, otherwise known as the cellular recycling process. Most people are “convinced they need to eat in order to live,” Miss Novak says, but this is wrong. She explains that not eating anything, ever, means her students will be part of an exclusive, underground club—hence the title—of people who have taken a stand against Big Food, who are members of a “worldwide association of people who don’t eat.” While at first some of the parents sound open to, if somewhat skeptical of, conscious eating, no food whatsoever raises an alarm. Take Elsa (Ksenia Devriendt), a student who already has bulimia, a condition her mother (Elsa Zylberstein) pretends she doesn’t notice. When Elsa switches to Miss Novak’s extreme form of anorexia, her father (Mathieu Demy) attempts to force her to eat. But Elsa’s rebellion against her parents is a gag-inducing display of eating her own vomit. Each of the students take their commitment to Miss Novak to disturbing levels, from one student forgoing his insulin shots to the finale—an ambiguous image that invites speculation.

Hausner’s style for Club Zero feels coldly Kubrickian, with long, tableau-like shots and patient zoom-outs reminiscent of the camerawork on Barry Lyndon (1975). Cinematographer Martin Gschlacht and editor Karina Ressler create a methodical rhythm, accented by Markus Binder’s eerie music that adds an uncanny twinge to most scenes. To be sure, there’s a subtle touch of surreality throughout, marked by Beck Rainford’s production design of pastel colors and yellow school uniforms. The presence of a “Nibbli” meat bar vending machine recalls a similar brand of processed food product from Bong Joon-ho’s Okja (2017), underscoring the exaggerated world. Miss Novak’s lessons also prove unsettling, not only for what she tells her students, such as not to tell their parents or other students about Club Zero, but also for the cultish humming in harmony during her lessons. Wasikowska is excellent in the role, though her character is distant and underdeveloped. While Wasikowska has done the Hollywood thing, she seems to have moved on, content to make offbeat, independent, and radical gems like this, in which she’s a welcome presence.

Tonally, the film’s closest companion might be David Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Future, which debuted at Cannes a year before Club Zero. Certainly, Hausner offers a Cronenbergian sense of body horror, with the children developing red and yellow blotches on their skin. But it’s more than that. The Canadian auteur considered a similar set of circumstances regarding food, albeit related to the consumption of plastics as a form of a bodily (r)evolution, coinciding with humanity’s rape of the environment via microplastics, pollution, and waste. Of course, Cronenberg wasn’t suggesting that people actually start munching on plastic (we’re already consuming enough of it), nor is Hausner telling viewers to stop eating. Rather, both films ask us to recognize how systems of control operate. It’s not just about food.

When Miss Novak tells her students, “The question is, why do we seek scientific proof for something that actually works?” her method of control is rooted in belief. And if the anti-science movement in the US and across the globe has taught us anything, it’s that blind faith can be frighteningly dangerous. In that sense, the film can feel like a horror movie at times, albeit one fashioned by Luis Buñuel and armed with a sharp sense of provocation and social commentary. Still, Hausner’s target can sometimes feel jumbled. Club Zero places blame on parents who don’t know what schools are teaching their children, religions and social movements that rely on radical thinking not rooted in science, and teens who open themselves up to radicalization by refusing to compromise their ideals. The film has a lot on its mind, and it’s not always focused on its messaging. Still, what it’s not doing is telling people not to eat. And it leaves the viewer with much to think about since Hausner points her fingers in a lot of directions.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review