Clown

By Brian Eggert |

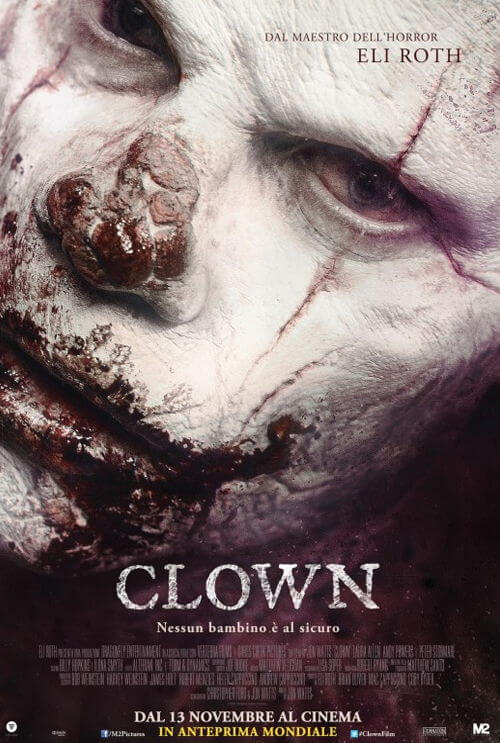

Director Jon Watts is best known for last year’s entertaining Sundance Film Festival hit Cop Car, starring Kevin Bacon as a dirty cop whose squad car is stolen by two runaway children. Largely because of that film, Marvel Entertainment and Sony hired Watts to direct Spider-Man: Homecoming—another superhero reboot for the iconic character, this time for the extended Marvel Cinematic Universe—scheduled to hit theaters in 2017. But before Cop Car, Watts directed and co-wrote Clown for producer Eli Roth (Knock Knock, The Green Inferno) and the Weinsteins’ Dimension Films. Though completed in 2014, Clown was never released theatrically, and perhaps only because of Watts’ deal with Marvel has it received a limited theatrical run and release on VOD in 2016.

Contrary to what you might imagine based on the poster, Clown wasn’t shelved because of a cheap, B-movie quality; the movie is actually made with technical skill. It doesn’t belong among the droves of forgotten direct-to-video horror titles streaming on Netflix. To be sure, Watts’ evident capabilities as a filmmaker elevate the movie above most lowbrow horror. It’s more likely that the Weinsteins made a moral choice to suppress the movie, given that it depicts the gory deaths of several young children. People can watch psycho killers dismember horny teenagers all day long, but they can’t handle young children facing peril. Many critics and viewers deplore synthesized violence against children in cinema; even putting children in indirect jeopardy remains frowned upon. And so, Clown was no doubt shelved because it serves up several children to a cannibalistic Bozo, and does so with a seedily horrifying tone.

The story involves an agreeable father, Kent (Andy Powers), who, to entertain his son’s birthday party guests, dons a mysterious clown costume he finds in the basement of a house he’s trying to sell as a realtor. Afterward, the rubber nose, costume, and rainbow-colored wig seem to have bonded with his body. He tries to remove them with a razor blade and handsaw, but his attempts prove unsuccessful. After doing some research, he finds the clown suit’s former owner (Peter Stormare), who warns the suit belongs to a clown-demon with an appetite for kids. Stricken with an insatiable stomach growling, Kent takes the warning seriously after he bites the fingers off a Cub Scout. Kent, realizing he’s doomed, then tries to kill himself with a bullet in the brain, but the multi-colored blowback and his sudden return to life suggest he won’t escape that easy.

For much of the film, Kent’s struggle to resist his hunger and his attempts to remove the costume evoke a strange kind of body -horror, like Cronenberg at a circus. Meanwhile, Kent’s wife (Laura Allen) tries to rescue her husband’s soul from the evil clown costume, and the outcome only produces increasingly vile death and child-eating. Unlike, say, last year’s Krampus, which had a laughably morbid sense of humor about children becoming victims to a monster, Watts and his co-writer Christopher D. Ford forego any sense of humor about the proceedings, especially during the grotesque second half. Aside from a few chuckles early on, Clown contains a dour tone. One can’t help but question whether it’s a good idea to make a humorless movie about a kid-craving clown demon. Nevertheless, Watts makes a solid effort at the disturbing concept, but the movie comes off as unpleasant, instead of unpleasant and fun.

Exploiting a commonly held fear of clowns—epitomized in our nightmares by Stephen King’s novel It—the movie proves unsettling from start to finish, but not necessarily in a good way. Whereas many horror movies create a certain level of entertainment value out of scaring their audience, Clown resolves to repulse and disturb, depicting horrific scenes of monstrous clown violence, largely against children, with a dependence on shock and gore. Whereas the basic premise of Clown had the potential of tapping into our latent fears of men (sadistic or genuinely pleasant, it doesn’t matter) dressed up as clowns, the movie resolves to be as unpleasant as possible. And while competently made and demonstrating Watts’ assured talent, the story and characters fail to engage in any way outside of disturbing us.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review