Cloud Atlas

By Brian Eggert |

Directors Andy Wachowski, Lana Wachowski, and Tom Tykwer expect a lot from the audience of Cloud Atlas, a motion picture set on the boundaries of time, genre, and conventional filmmaking. At once, the viewer must be able to process six separate stories that span five periods in time as the filmmakers dance backward and forward among them, the ambitious structure reformatting David Mitchell’s 2004 novel. Each story follows a distinct genre, among them drama, comedy, tragedy, thriller, science-fiction, and adventure. An audience must identify how the impressive ensemble of actors has separate roles in each story, emphasizing the epic configuration as one of interconnectivity, while the themes throughout the various stories mirror and often take cues from one another. Decoding exactly how these complicated and interwoven elements form a whole is less important than the feeling of something larger behind it all. By the end of this 172-minute wonder, the viewer need only recognize the implementation, power, and tradition of great storytelling.

Funded independently by mostly German money and distributed in the U.S. by Warner Bros., Cloud Atlas must be one of the most aspiring and expensive independent films ever produced. Securing a budget of over $100 million, German filmmaker Tykwer (Run Lola Run) teamed with the Wachowskis (Speed Racer) for a picture they all must have known would not appeal to the masses. No matter how successful the Wachowski siblings’ actionized, pseudo-intellectual Matrix trilogy may have been, certainly no Hollywood studio would put forth the backing necessary to erect a seemingly impenetrable, “unfilmable” novel into a heady, near-3-hour film whose result would be inevitable polarization of the masses. And yet, nothing about this production feels inaccessible or reminiscent of a picture with any limitations whatsoever. From the pristine quality of the special FX to the sheer scope of the sets, this is a film without margins. Every facet looks like that of a major Hollywood production, except it’s infused with the poetic and philosophical insights of filmmakers working outside of a major studio.

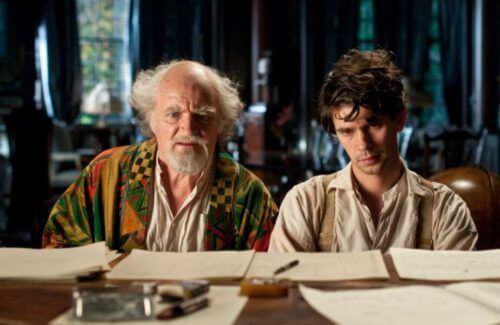

The directors’ best visual resource, however, remains the cast. Assembled here are Tom Hanks, Halle Berry, Hugh Grant, Jim Broadbent, Jim Sturgess, Keith David, Ben Wishaw, Doona Bae, Hugo Weaving, James D’Arcy, Susan Sarandon, and Zhou Xun. Each plays multiple roles, most with a major part in at least one story, and most occupying races and genders not their own during one of their supporting roles. To describe them all would be far-reaching and time-consuming, but consider this example: Berry plays an investigative reporter, a Jewish woman, a slave, a male South Korean doctor, an Indian woman, and a member of a technologically enhanced future race. Each role for each actor comes with an individual makeup design, transforming these performers and their protagonists in ways that make the viewer’s experience an investigative one. Some of the costumes are less successful than others, such as when Doona Bae becomes an awkward British lass, but the narrative symbolism behind these choices speaks volumes. Though narrow viewers may find dressing up one race as another to be in poor taste, racial representations are indiscriminate and bound by a greater purpose, the effect emphasizing the film’s stable theme of “eternal recurrence”—the notion that within infinite time and space, existence will cycle and recur an infinite number of times.

The stories themselves range from the mid-19th century to a distant post-apocalyptic futureworld. Chronologically, the film begins with “The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing” in 1850, following a naïve notary (Sturgess) who, while at sea, defends the life of a Moriori tribe stowaway and finds himself poisoned by a duplicitous friend. Next comes “Letters from Zedelghem,” a 1931 account of a struggling musician (Wishaw) who writes letters to his illicit male lover and becomes an apprentice to an idolized composer. “Half-Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery” takes place in the 1970s and proceeds like The China Syndrome, where a reporter (Berry) uncovers a sinister plot involving a nuclear power executive (Grant), a deadly conspiracy, and a ruthless assassin (Weaving). Present day finds “The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish”, where an aged publisher (Broadbent) is interned inside an appalling senior care facility from where he plots to escape. In the mid-22nd century, “An Orison of Sonmi~451” tells of a genetically engineered servant (Bae) in a dystopian Neo Seoul; after being rescued from certain death by rebel forces, she becomes a figurehead for an uprising against The Powers That Be. In the final, mythic story called “Sloosha’s Crossin’ an’ Ev’rythin’ After”, set in the distant, post-apocalyptic future, a primitive tribesman (Hanks) guides a woman from an elite race (Berry) to a place on his island where the remains of a long lost culture still stand.

Along with a vast array of characters, their similarities, and reincarnated souls, there are amazing sights to behold in Cloud Atlas. Most apparent are the futurist sequences, with elaborate sci-fi chases on energized highways along a vast, neon-laden cityscape; or there’s the crumbled post-apocalyptic world where Hanks’ character is plagued by a devilish, green-skinned whisperer (Weaving) spouting lies and suspicions in his ear. These most audacious examples, directed by the Wachowskis, might threaten to overshadow the subtleties of Tykwer’s contributions in the past and present segments, where his immersion into historical details is flawless, and his characters have far more dramatically complicated circumstances. The most affecting tale involves the relationship between the struggling musician and his devoted lover, while the most heartwarming concerns the comical senior citizens revolting against a crooked Nurse Ratched figure (Weaving). As a whole, there’s something for everyone here; but for those not pulled toward this or that genre, the entire picture remains enthralling.

To explore the individual stories and their precise connections to one another in more detail would be futile for the purpose of this review; let us instead consider the structure and themes. Within each tale, there are varied methods and devices of storytelling: novels, personal letters, journals, motion pictures, pictorials, and the oral tradition. Mitchell’s book unfolded sequentially, telling the first half of each story from the participants’ perspective, and the second within a separate story from the perspective of someone else reading about or watching it in video form. But the trio of directors uses a bravado structure that aligns the narrative beats of every story, cross-cutting through time to further highlight how every story is different, yet every story is the same. Emotional aches and suspenseful turns seem to occur across time but in harmony with one another inside the film’s composition. As such, there are recurring themes throughout—class struggles, elitist monsters, betrayal, slavery, humanist revolution, and most transcendently, love. Each ripples across time, and each resonates in separate ways. Some are joyful, others harrowing, others still hilarious or exciting. Our involvement is never limited to a single emotional reaction, but the capacity to feel the breadth of emotions from one moment to the next is essential.

To explore the individual stories and their precise connections to one another in more detail would be futile for the purpose of this review; let us instead consider the structure and themes. Within each tale, there are varied methods and devices of storytelling: novels, personal letters, journals, motion pictures, pictorials, and the oral tradition. Mitchell’s book unfolded sequentially, telling the first half of each story from the participants’ perspective, and the second within a separate story from the perspective of someone else reading about or watching it in video form. But the trio of directors uses a bravado structure that aligns the narrative beats of every story, cross-cutting through time to further highlight how every story is different, yet every story is the same. Emotional aches and suspenseful turns seem to occur across time but in harmony with one another inside the film’s composition. As such, there are recurring themes throughout—class struggles, elitist monsters, betrayal, slavery, humanist revolution, and most transcendently, love. Each ripples across time, and each resonates in separate ways. Some are joyful, others harrowing, others still hilarious or exciting. Our involvement is never limited to a single emotional reaction, but the capacity to feel the breadth of emotions from one moment to the next is essential.

Cloud Atlas opens with one of the many characters played by Tom Hanks recounting tales around a fire. From his aged, wrinkled face comes a grizzled voice, and a horrible scar down his face cuts across his one pale eye. He might be an ancient caveman grunting out his tale, but in fact, he belongs to the distant future. Time is relative, but all remains the same. What a simple, rather beautiful notion behind such an uncommonly grand piece of filmmaking, whose ideas will either speak volumes or completely dismiss whole sections of the audience. Undeniable is the profound vision of Tykwer and the Wachowskis, who approach Terrence Malick (The Tree of Life) territory in that their divisive film is less an intellectual viewing than something that must be felt and experienced, perhaps multiple times, to truly grasp its meaning—or, at least, what it means to you. Amid the spell of visual and narrative connections, beyond question, Cloud Atlas will confound and maybe even aggravate some unwilling to, quite simply, “go with the flow.” But others will find what few have: a bold, technically awesome, and thematically enduring picture whose arrangement and ambition are unprecedented.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review